Just as they have helped to illuminate some of the routes through which our moods influence our cognition, so social cognitive researchers have also contributed to our knowledge of how our thoughts can change our moods. Indeed, some researchers have argued that affective experiences are only possible following cognitive appraisals. Although physiological arousal is necessary for emotion, many have argued that it is not sufficient (Lazarus, 1984). Under this view, arousal becomes emotion only when it is accompanied by a label or by an explanation for the arousal (Schachter & Singer, 1962). If this is correct, then emotions have two factors—an arousal factor and a cognitive factor (James, 1890; Schachter & Singer, 1962).

In some cases, it may be difficult for people who are experiencing a high level of arousal to accurately determine which emotion they are experiencing. That is, they may be certain that they are feeling arousal, but the meaning of the arousal (the cognitive factor) may be less clear. Some romantic relationships, for instance, are characterized by high levels of arousal, and the partners alternately experience extreme highs and lows in the relationship. One day they are madly in love with each other, and the next they are having a huge fight. In situations that are accompanied by high arousal, people may be unsure what emotion they are experiencing. In the high-arousal relationship, for instance, the partners may be uncertain whether the emotion they are feeling is love, hate, or both at the same time. Misattribution of arousal occurs when people incorrectly label the source of the arousal that they are experiencing.

Research Focus: Misattributing Arousal

If you think a bit about your own experiences of different emotions, and if you consider the equation that suggests that emotions are represented by both arousal and cognition, you might

start to wonder how much was determined by each. That is, do we know what emotion we are experiencing by monitoring our feelings (arousal) or by monitoring our thoughts (cognition)?

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) addressed this question in a well-known social psychological experiment. Schachter and Singer believed that the cognitive part of the emotion was

critical—in fact, they believed that the arousal that we are experiencing could be interpreted as any emotion, provided we had the right label for it. Thus they hypothesized that if

individuals are experiencing arousal for which they have no immediate explanation, they will “label” this state in terms of the cognitions that are most accessible in the environment. On the

other hand, they argued that people who already have a clear label for their arousal would have no need to search for a relevant label and therefore should not experience an emotion. In the

research experiment, the male participants were told that they would be participating in a study on the effects of a new drug, called “suproxin,” on vision. On the basis of this cover story,

the men were injected with a shot of epinephrine, a drug that produces physiological arousal. The idea was to give all the participants arousal; epinephrine normally creates feelings of

tremors, flushing, and accelerated breathing in people.

Then, according to random assignment to conditions, the men were told that the drug would make them feel certain ways. The men in the epinephrine-informed condition were told the truth about

the effects of the drug—they were told that other participants had experienced tremors and that their hands would start to shake, their hearts would start to pound, and their faces might get

warm and flushed. The participants in the epinephrine-uninformed condition, however, were told something untrue—that their feet would feel numb, that they would have an itching sensation over

parts of their body, and that they might get a slight headache. The idea was to make some of the men think that the arousal they were experiencing was caused by the drug (the informed

condition), whereas others would be unsure where the arousal came from (the uninformed condition). Then the men were left alone with a confederate who they thought had received the same

injection. While they were waiting for the experiment (which was supposedly about vision) to begin, the confederate behaved in a wild and crazy (Schachter and Singer called it “euphoric”)

manner. He wadded up spitballs, flew paper airplanes, and played with a hula hoop. He kept trying to get the participants to join in his games. Then right before the vision experiment was to

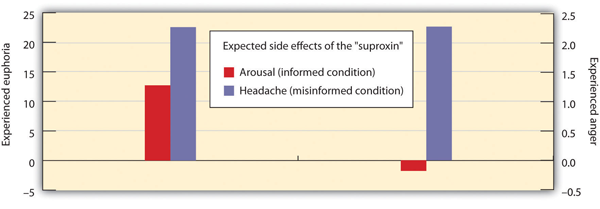

begin, the participants were asked to indicate their current emotional states on a number of scales. One of the emotions they were asked about was euphoria. If you are following the story

here, you will realize what was expected—that the men who had a label for their arousal (the informed group) would not be experiencing much emotion—they had a label already available for

their arousal. The men in the misinformed group, on the other hand, were expected to be unsure about the source of the arousal—they needed to find an explanation for their arousal, and the

confederate provided one. Indeed, as you can see in Figure 2.19, this is just what the researchers found. Then Schachter and Singer did another part of the study, using new participants. Everything was exactly the same except

for the behavior of the confederate. Rather than being euphoric, he acted angry. He complained about having to complete the questionnaire he had been asked to do, indicating that the

questions were stupid and too personal. He ended up tearing up the questionnaire that he was working on, yelling, “I don’t have to tell them that!” Then he grabbed his books and stormed out

of the room. What do you think happened in this condition? The answer, of course, is, exactly the same thing—the misinformed participants experienced more anger than did the informed

participants. The idea is that because cognitions are such strong determinants of emotional states, the same state of physiological arousal could be labeled in many different ways, depending

entirely on the label provided by the social situation. We will revisit the effects of misattribution of arousal when we consider sources of romantic attraction.

So, our attribution of the sources of our arousal will often strongly influence the emotional states we experience in social situations. How else might our cognition influence our affect? Another example is demonstrated in framing effects, which occur when people’s judgments about different options are affected by whether they are framed as resulting in gains or losses. In general, people feel more positive about options that are framed positively, as opposed to negatively. For example, individuals seeking to eat healthily tend to feel more positive about a product described as 95% fat free than one described as 5% fat, even though the information in the two messages is the same. In the same way, people tend to prefer treatment options that stress survival rates as opposed to death rates. Framing effects have been demonstrated in regards to numerous social issues, including judgments relating to charitable donations (Chang & Lee, 2010) and green environmental practices (Tu, Kao, & Tu, 2013). In reference to our chapter case study, they have also been implicated in decisions about risk in financial contexts and in the explanation of market behaviors (Kirchler, Maciejovsky, & Weber, 2010).

Social psychologists have also studied how we use our cognitive faculties to try to control our emotions in social situations, to prevent them from letting our behavior get out of control. The process of setting goals and using our cognitive and affective capacities to reach those goals is known as self-regulation, and a good part of self-regulation involves regulating our emotions. To be the best people that we possibly can, we have to work hard at it. Succeeding at school, at work, and at our relationships with others takes a lot of effort. When we are successful at self-regulation, we are able to move toward or meet the goals that we set for ourselves. When we fail at self-regulation, we are not able to meet those goals. People who are better able to regulate their behaviors and emotions are more successful in their personal and social encounters (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992), and thus self-regulation is a skill we should seek to master.

A significant part of our skill in self-regulation comes from the deployment of cognitive strategies to try to harness positive emotions and to overcome more challenging ones. For example, to achieve our goals we often have to stay motivated and to be persistent in the face of setbacks. If, for example, an employee has already gone for a promotion at work and has been unsuccessful twice before, this could lead him or her to feel very negative about his or her competence and the possibility of trying for promotion again, should an opportunity arise. In these types of challenging situations, the strategy of cognitive reappraisal can be a very effective way of coping. Cognitive reappraisal involves altering an emotional state by reinterpreting the meaning of the triggering situation or stimulus. For example, if another promotion position does comes up, the employee could reappraise it as an opportunity to be successful and focus on how the lessons learned in previous attempts could strengthen his or her candidacy this time around. In this case, the employee would likely feel more positive towards the opportunity and choose to go after it.

Using strategies like cognitive reappraisal to self-regulate negative emotional states and to exert greater self-control in challenging situations has some important positive outcomes. Consider, for instance, research by Walter Mischel and his colleagues (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989). In their studies, they had four- and five-year-old children sit at a table in front of a yummy snack, such as a chocolate chip cookie or a marshmallow. The children were told that they could eat the snack right away if they wanted to. However, they were also told that if they could wait for just a couple of minutes, they’d be able to have two snacks—both the one in front of them and another just like it. However, if they ate the one that was in front of them before the time was up, they would not get a second.

Mischel found that some children were able to self-regulate—they were able to use their cognitive abilities to override the impulse to seek immediate gratification in order to obtain a greater reward at a later time. Other children, of course, were not—they just ate the first snack right away. Furthermore, the inability to delay gratification seemed to occur in a spontaneous and emotional manner, without much thought. The children who could not resist simply grabbed the cookie because it looked so yummy, without being able to cognitively stop themselves (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999; Strack & Deutsch, 2007).

The ability to self-regulate in childhood has important consequences later in life. When Mischel followed up on the children in his original study, he found that those who had been able to self-regulate as children grew up to have some highly positive characteristics—they got better SAT scores, were rated by their friends as more socially adept, and were found to cope with frustration and stress better than those children who could not resist the tempting first cookie at a young age. Effective self-regulation is therefore an important key to success in life (Ayduk et al., 2000; Eigsti et al., 2006; Mischel, Ayduk, & Mendoza-Denton, 2003).

Self-regulation is difficult, though, particularly when we are tired, depressed, or anxious, and it is under these conditions that we more easily lose our self-control and fail to live up to our goals (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). If you are tired and worried about an upcoming test, you may find yourself getting angry and taking it out on your friend, even though your friend really hasn’t done anything to deserve it and you don’t really want to be angry. It is no secret that we are more likely to fail at our diets when we are under a lot of stress or at night when we are tired. In these challenging situations, and when our resources are particularly drained, the ability to use cognitive strategies to successfully self-regulate becomes more even more important, and difficult.

Muraven, Tice, and Baumeister (1998) conducted a study to demonstrate that emotion regulation—that is, either increasing or decreasing our emotional responses—takes work. They speculated that self-control was like a muscle—it just gets tired when it is used too much. In their experiment, they asked their participants to watch a short movie about environmental disasters involving radioactive waste and their negative effects on wildlife. The scenes included sick and dying animals, which were very upsetting. According to random assignment to conditions, one group (the increase-emotional-response condition) was told to really get into the movie and to express emotions in response to it, a second group was to hold back and decrease emotional responses (the decrease-emotional-response condition), and a third (control) group received no instructions on emotion regulation.

Both before and after the movie, the experimenter asked the participants to engage in a measure of physical strength by squeezing as hard as they could on a hand-grip exerciser, a device used for building up hand muscles. The experimenter put a piece of paper in the grip and timed how long the participants could hold the grip together before the paper fell out. Table 2.2 shows the results of this study. It seems that emotion regulation does indeed take effort because the participants who had been asked to control their emotions showed significantly less ability to squeeze the hand grip after the movie than before. Thus the effort to regulate emotional responses seems to have consumed resources, leaving the participants less capacity to make use of in performing the hand-grip task.

|

Condition |

Handgrip strength before movie |

Handgrip strength after movie |

Change |

|

Increase emotional response |

78.73 |

54.63 |

–25.1 |

|

No emotional control |

60.09 |

58.52 |

–1.57 |

|

Decrease emotional response |

70.74 |

52.25 |

–18.49 |

|

Participants who had been required to either express or refrain from expressing their emotions had less strength to squeeze a hand grip after doing so. Data are from Muraven et al. (1998). |

|||

In other studies, people who had to resist the temptation to eat chocolates and cookies, who made important decisions, or who were forced to conform to others all performed more poorly on subsequent tasks that took energy in comparison to people who had not been emotionally taxed. After controlling their emotions, they gave up on subsequent tasks sooner and failed to resist new temptations (Vohs & Heatherton, 2000).

Can we improve our emotion regulation? It turns out that training in self-regulation—just like physical training—can help. Students who practiced doing difficult tasks, such as exercising, avoiding swearing, or maintaining good posture, were later found to perform better in laboratory tests of self-regulation (Baumeister, Gailliot, DeWall, & Oaten, 2006; Baumeister, Schmeichel, & Vohs, 2007; Oaten & Cheng, 2006), such as maintaining a diet or completing a puzzle.

- 6917 reads