Although there continues to be a lively debate within the social psychological literature about the relative contributions of each factor, it is clear that helping is both part of our basic human biological nature and also in part learned through our social experiences with other people (Batson, 2011).

The principles of social learning suggest that people will be more likely to help when they receive rewards for doing so. Parents certainly realize this—children who share their toys with others are praised, whereas those who act more selfishly are reprimanded. And research has found that we are more likely to help attractive rather than unattractive people of the other sex (Farrelly, Lazarus, & Roberts, 2007)—again probably because it is rewarding to do so.

Darley and Batson (1973) demonstrated the effect of the costs of helping in a particularly striking way. They asked students in a religious seminary to prepare a speech for presentation to other students. According to random assignment to conditions, one half of the seminarians prepared a talk on the parable of the altruistic Good Samaritan; the other half prepared a talk on the jobs that seminary students like best. The expectation was that preparing a talk on the Good Samaritan would prime the concept of being helpful for these students.

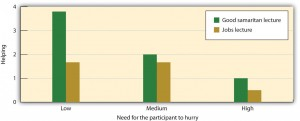

After they had prepared their talks, the religion students were then asked to walk to a nearby building where the speech would be recorded. However, and again according to random assignment, the students were told that they had plenty of time to get to the recording session, that they were right on time, or that they should hurry because they were already running late. On the way to the other building, the students all passed a person in apparent distress (actually a research confederate) who was slumped in a doorway, coughing and groaning, and clearly in need of help. The dependent variable in the research was the degree of helping that each of the students gave to the person who was in need (Figure 8.5).

Darley and Batson found that the topic of the upcoming speech did not have a significant impact on helping. The students who had just prepared a speech about the importance of helping did not help significantly more than those who had not. Time pressure, however, made a difference. Of those who thought they had plenty of time, 63% offered help, compared with 45% of those who believed they were on time and only 10% of those who thought they were late. You can see that this is exactly what would be expected on the basis of the principles of social reinforcement—when we have more time to help, then helping is less costly and we are more likely to do it.

The seminary students in the research by Darley and Batson (1973) were less likely to help a person in need when they were in a hurry than when they had more time, even when they were actively preparing a talk on the Good Samaritan. The dependent measure is a 5-point scale of helping, ranging from “failed to notice the victim at all” to “after stopping, refused to leave the victim or took him for help.”

Of course, not all helping is equally costly. The costs of helping are especially high when the situation is potentially dangerous or when the helping involves a long-term commitment to the person in need, such as when we decide to take care of a very ill person. Because helping strangers is particularly costly, some European countries have enacted Good Samaritan laws that increase the costs of not helping others. These laws require people to provide or call for aid in an emergency if they can do so without endangering themselves in the process, with the threat of a fine or other punishment if they do not. Many countries and states also have passed “angel of mercy” laws that decrease the costs of helping and encourage people to intervene in emergencies by offering them protection from the law if their actions turn out not to be helpful or even harmful. For instance, in Germany, a failure to provide first aid to someone in need is punishable by a fine. Furthermore, to encourage people to help in any way possible, the individual providing assistance cannot be prosecuted even if he or she made the situation worse or did not follow proper first aid guidelines (Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz, 2014).

In addition to learning through reinforcement, we are also likely to help more often when we model the helpful behavior of others (Bryan & Test, 1967). In fact, although people frequently worry about the negative impact of the violence that is seen on TV, there is also a great deal of helping behavior shown on TV. Smith et al. (2006) found that 73% of TV shows had some altruism and that about three altruistic behaviors were shown every hour. Furthermore, the prevalence of altruism was particularly high in children’s shows.

Viewing positive role models provides ideas about ways to be helpful to others and gives us information about appropriate helping behaviors. Research has found a strong correlation between viewing helpful behavior on TV and helping. Hearold (1980) concluded on the basis of a meta-analysis that watching altruism on TV had a larger effect on helping than viewing TV violence had on aggressive behavior. She encouraged public officials and parents to demand more TV shows with prosocial themes and positive role models. But just as viewing altruism can increase helping, modeling of behavior that is not altruistic can decrease altruism. Anderson and Bushman (2001) found that playing violent video games led to a decrease in helping.

There are still other types of rewards that we gain from helping others. One is the status we gain as a result of helping. Altruistic behaviors serve as a type of signal about the altruist’s personal qualities. If good people are also helpful people, then helping implies something good about the helper. When we act altruistically, we gain a reputation as a person with high status who is able and willing to help others, and this status makes us better and more desirable in the eyes of others. Hardy and Van Vugt (2006) found that both men and women were more likely to make cooperative rather than competitive choices in games that they played with others when their responses were public rather than private. Furthermore, when the participants made their cooperative choices in public, the participants who had been more cooperative were also judged by the other players as having higher social status than were the participants who had been less cooperative.

Finally, helpers are healthy! Research has found that people who help are happier and even live longer than those who are less helpful (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003).

- 4885 reads