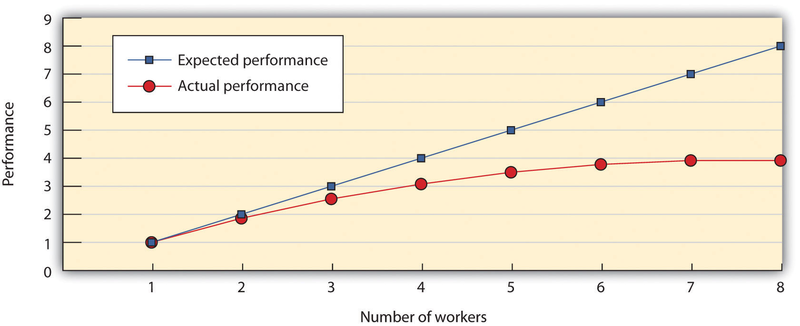

In a seminal study of group effects on individual performance, Ringelmann (1913; reported in Kravitz & Martin, 1986) investigated the ability of individuals to reach their full potential when working together on tasks. Ringelmann had individual men and groups of various numbers of men pull as hard as they could on ropes while he measured the maximum amount that they were able to pull. Because rope pulling is an additive task, the total amount that could be pulled by the group should be the sum of the contributions of the individuals. However, as shown in Figure 10.8, although Ringelmann did find that adding individuals to the group increased the overall amount of pulling on the rope (the groups were better than any one individual), he also found a substantial process loss. In fact, the loss was so large that groups of three men pulled at only 85% of their expected capability, whereas groups of eight pulled at only 37% of their expected capability.

Ringelmann found that although more men pulled harder on a rope than fewer men did, there was a substantial process loss in comparison with what would have been expected on the basis of their individual performances.

This type of process loss, in which group productivity decreases as the size of the group increases, has been found to occur on a wide variety of tasks, including maximizing tasks such as clapping and cheering and swimming (Latané, Williams, & Harkins, 1979; Williams, Nida, Baca, & Latané, 1989), and judgmental tasks such as evaluating a poem (Petty, Harkins, Williams, & Latané, 1977). Furthermore, these process losses have been observed in different cultures, including India, Japan, and Taiwan (Gabrenya, Wang, & Latané, 1985; Karau & Williams, 1993).

Process losses in groups occur in part simply because it is difficult for people to work together. The maximum group performance can only occur if all the participants put forth their greatest effort at exactly the same time. Since, despite the best efforts of the group, it is difficult to perfectly coordinate the input of the group members, the likely result is a process loss such that the group performance is less than would be expected, as calculated as the sum of the individual inputs. Thus actual productivity in the group is reduced in part by these coordination losses.

Coordination losses become more problematic as the size of the group increases because it becomes correspondingly more difficult to coordinate the group members. Kelley, Condry, Dahlke, and Hill (1965) put individuals into separate booths and threatened them with electrical shock. Each person could avoid the shock, however, by pressing a button in the booth for three seconds. But the situation was arranged so that only one person in the group could press the button at one time, and therefore the group members needed to coordinate their actions. Kelley and colleagues found that larger groups had significantly more difficulty coordinating their actions to escape the shocks than did smaller groups.

However, coordination loss at the level of the group is not the only explanation of reduced performance. In addition to being influenced by the coordination of activities, group performance is influenced by self-concern on the part of the individual group members. Since each group member is motivated at least in part by individual self-concerns, each member may desire, at least in part, to gain from the group effort without having to contribute very much. You may have been in a work or study group that had this problem—each group member was interested in doing well but also was hoping that the other group members would do most of the work for them. A group process loss that occurs when people do not work as hard in a group as they do when they are alone is known as social loafing (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Research Focus: Differentiating Coordination Losses from Social Loafing

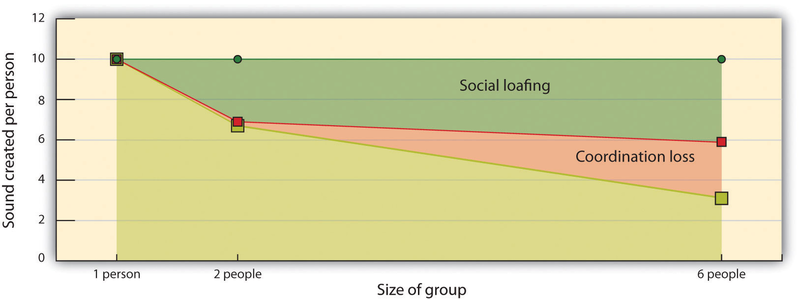

Latané, Williams, and Harkins (1979) conducted an experiment that allowed them to measure the extent to which process losses in groups were caused by coordination losses and by social loafing. Research participants were placed in a room with a microphone and were instructed to shout as loudly as they could when a signal was given. Furthermore, the participants were blindfolded and wore headsets that prevented them from either seeing or hearing the performance of the other group members. On some trials, the participants were told (via the headsets) that they would be shouting alone, and on other trials, they were told that they would be shouting with other participants. However, although the individuals sometimes did shout in groups, in other cases (although they still thought that they were shouting in groups) they actually shouted alone. Thus Latané and his colleagues were able to measure the contribution of the individuals, both when they thought they were shouting alone and when they thought they were shouting in a group. The results of the experiment are presented in ***Figure 10.8***, which shows the amount of sound produced per person. The top line represents the potential productivity of the group, which was calculated as the sum of the sound produced by the individuals as they performed alone. The middle line represents the performance of hypothetical groups, computed by summing the sound in the conditions in which the participants thought that they were shouting in a group of either two or six individuals, but where they were actually performing alone. Finally, the bottom line represents the performance of real two-person and six-person groups who were actually shouting together.

Individuals who were asked to shout as loudly as they could shouted much less so when they were in larger groups, and this process loss was the result of both motivation and coordination

losses. Data from Latané, Williams, and Harkins (1979). The results of the study are very clear. First, as the number of people in the group increased (from one to two to six), each person’s

individual input got smaller, demonstrating the process loss that the groups created. Furthermore, the decrease for real groups (the lower line) is greater than the decrease for the groups

created by summing the contributions of the individuals. Because performance in the summed groups is a function of motivation but not coordination, and the performance in real groups is a

function of both motivation and coordination, Latané and his colleagues effectively showed how much of the process loss was due to each. Social loafing is something that everyone both engages

in and is on the receiving end of from time to time. It has negative effects on a wide range of group endeavors, including class projects (Ferrari & Pychyl, 2012), occupational

performance (Ülke, & Bilgiç, 2011), and team sports participation (Høigaard, Säfvenbom, & Tønnessen, 2006). Given its many social costs, what can be done to reduce social loafing? In

a meta-analytic review, Karau and Williams (1993) concluded that loafing is more likely when groups are working on additive than non-additive tasks. They also found that it was reduced when

the task was meaningful and important to group members, when each person was assigned identifiable areas of responsibility, and was recognized and praised for the contributions that he or she

made. These are some important lessons for all us to take forward here, for the next time we have to complete a group project, for instance!

As well as being less likely to occur in certain tasks under certain conditions, there are also some personal factors that affect rates of social loafing. On average, women loaf less than men

(Karau & Williams, 1993). Men are also more likely to react to social rejection by loafing, whereas women tend to work harder following rejection (Williams & Sommer, 1997). These

findings could well help to shed some light on our chapter case study, where we noted that mixed-gender corporate boards outperformed their all-male counterparts. Simply put, we would predict

that groups that included women would engage in less loafing, and would therefore show higher performance. Culture, as well as gender, has been shown to affect rates of the social loafing. On

average, people in individualistic cultures loaf more than those in collectivistic cultures, where the greater emphasis on interdependence can sometimes make people work harder in groups than

on their own (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Key Takeaways

- In some situations, social inhibition reduces individuals’ performance in group settings, whereas in other settings, group facilitation enhances individual performance.

- Although groups may sometimes perform better than individuals, this will occur only when the people in the group expend effort to meet the group goals and when the group is able to efficiently coordinate the efforts of the group members.

- The benefits or costs of group performance can be computed by comparing the potential productivity of the group with the actual productivity of the group. The difference will be either a process loss or a process gain.

- Group member characteristics can have a strong effect on group outcomes, but to fully understand group performance, we must also consider the particulars of the group’s situation.

- Classifying group tasks can help us understand the situations in which groups are more or less likely to be successful.

- Some group process losses are due to difficulties in coordination and motivation (social loafing).

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Outline a group situation where you experienced social inhibition. What task were you performing and why do you think your performance suffered?

- Describe a time when your performance improved through social facilitation. What were you doing, and how well do you think Zajonc’s theory explained what happened?

- Consider a time when a group that you belonged to experienced a process loss. Which of the factors discussed in this section do you think were important in creating the problem?

- In what situations in life have you seen other people social loafing most often? Why do you think that was? Describe some times when you engaged in social loafing and outline which factors from the research we have discussed best explained your loafing behavior?

References

Armstrong, J. S. (2001). Principles of forecasting: A handbook for researchers and practitioners. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Baumeister, R. F., & Steinhilber, A. (1984). Paradoxical effects of supportive audiences on performance under pressure: The home field disadvantage in sports championships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(1), 85–93.

Bond, C. F., & Titus, L. J. (1983). Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies. Psychological Bulletin, 94(2), 265–292.

Einhorn, H. J., Hogarth, R. M., & Klempner, E. (1977). Quality of group judgment. Psychological Bulletin, 84(1), 158–172.

Ferrari, J. R., & Pychyl, T. A. (2012). ‘If I wait, my partner will do it:’ The role of conscientiousness as a mediator in the relation of academic procrastination and perceived social loafing. North American Journal Of Psychology, 14< (1), 13-24.

Gabrenya, W. K., Wang, Y., & Latané, B. (1985). Social loafing on an optimizing task: Cross-cultural differences among Chinese and Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 16(2), 223–242.

Geen, R. G. (1989). Alternative conceptions of social facilitation. In P. Paulus (Ed.), Psychology of group influence (2nd ed., pp. 15–51). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Guerin, B. (1983). Social facilitation and social monitoring: A test of three models. British Journal of Social Psychology, 22(3), 203–214.

Hackman, J., & Morris, C. (1975). Group tasks, group interaction processes, and group performance effectiveness: A review and proposed integration. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 8, pp. 45–99). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Høigaard, R., Säfvenbom, R., & Tønnessen, F. (2006). The Relationship Between Group Cohesion, Group Norms, and Perceived Social Loafing in Soccer Teams. Small Group Research,37(3), 217-232.

Johnson, D.W., & Johnson, F.P. (2012). Joining together – group theory and group skills (11th ed). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Jones, M. B. (1974). Regressing group on individual effectiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 11(3), 426–451.

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681–706.

Kelley, H. H., Condry, J. C., Jr., Dahlke, A. E., & Hill, A. H. (1965). Collective behavior in a simulated panic situation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1, 19–54.

Kravitz, D. A., & Martin, B. (1986). Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 936–941.

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822–832.

Lorge, I., Fox, D., Davitz, J., & Brenner, M. (1958). A survey of studies contrasting the quality of group performance and individual performance, 1920-1957. Psychological Bulletin,55(6), 337-372.

Markus, H. (1978). The effect of mere presence on social facilitation: An unobtrusive test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14, 389–397.

Nijstad, B. A., Stroebe, W., & Lodewijkx, H. F. M. (2006). The illusion of group productivity: A reduction of failures explanation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(1), 31–48. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.295

Petty, R. E., Harkins, S. G., Williams, K. D., & Latané, B. (1977). The effects of group size on cognitive effort and evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(4), 579–582.

Robinson-Staveley, K., & Cooper, J. (1990). Mere presence, gender, and reactions to computers: Studying human-computer interaction in the social context. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26(2), 168–183.

Straus, S. G. (1999). Testing a typology of tasks: An empirical validation of McGrath’s (1984) group task circumplex. Small Group Research, 30(2), 166–187.

Strube, M. J., Miles, M. E., & Finch, W. H. (1981). The social facilitation of a simple task: Field tests of alternative explanations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 7(4), 701–707.

Surowiecki, J. (2004). The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, societies, and nations (1st ed.). New York, NY: Doubleday.

Szymanski, K., & Harkins, S. G. (1987). Social loafing and self-evaluation with a social standard. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(5), 891–897.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9(4), 507–533.

Ülke, H., & Bilgiç, R. (2011). Investigating the role of the big five on the social loafing of information technology workers. International Journal Of Selection And Assessment, 19(3), 301-312.

Weber, B., & Hertel, G. (2007). Motivation gains of inferior group members: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 973–993.

Williams, K. D., Nida, S. A., Baca, L. D., & Latané, B. (1989). Social loafing and swimming: Effects of identifiability on individual and relay performance of intercollegiate swimmers. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10(1), 73–81.

Williams, K. D., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation?.Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin,23(7), 693-706.

Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149, 269–274.

Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(2), 83–92.

- 10454 reads