Now that we have a fundamental understanding of the variables that influence the likelihood that we will help others, let’s spend some time considering how we might use this information in our everyday life to try to become more helpful ourselves and to encourage those around us to do the same. In doing so, we will make use of many of the principles of altruism that we have discussed in this chapter.

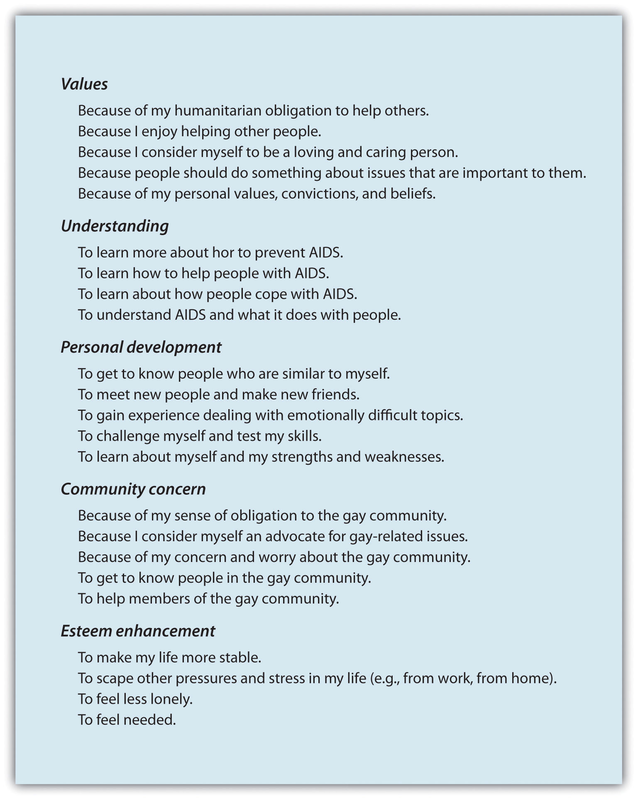

First, we need to remember that not all helping is based on other-concern—self-concern is also important. People help in part because it makes them feel good, and therefore anything that we can do to increase the benefits of helping and to decrease the costs of helping would be useful. Consider, for instance, the research of Mark Snyder, who has extensively studied the people who volunteer to help other people who are suffering from AIDS (Snyder & Omoto, 2004; Snyder, Omoto, & Lindsay, 2004). To help understand which volunteers were most likely to continue to volunteer over time, Snyder and his colleagues (Omoto & Snyder, 1995) asked the AIDS volunteers to indicate why they volunteered. As you can see in Figure 8.12, the researchers found that the people indicated that they volunteered for many different reasons, and these reasons fit well with our assumptions about human nature—they involve both self-concern as well as other-concern.

Omoto and Snyder (1995) found that the volunteers were more likely to continue their volunteer work if their reasons for volunteering involved self-related activities, such as understanding, personal development, or esteem enhancement. The volunteers who felt that they were getting something back from their work were likely to stay involved. In addition, Snyder and his colleagues found that that people were more likely to continue volunteering when their existing social support networks were weak. This result suggests that some volunteers were using the volunteer opportunity to help them create better social connections (Omoto & Snyder, 1995). On the other hand, the volunteers who reported experiencing negative reactions about their helping from their friends and family members, which made them feel embarrassed, uncomfortable, and stigmatized for helping, were also less likely to continue working as volunteers (Snyder, Omoto, & Crain, 1999).

These results again show that people will help more if they see it as rewarding. So if you want to get people to help, try to increase the rewards of doing so, for instance, by enhancing their mood or by offering incentives. Simple things, such as noticing, praising, and even labeling helpful behavior can be enough. When children are told that they are “kind and helpful children,” they contribute more of their prizes to other children (Grusec, Kuczynski, Rushton, & Simutis, 1978). Rewards work for adults too: people were more likely to donate to charity several weeks after they were described by another person as being “generous” and “charitable” people (Kraut, 1973). In short, once we start to think of ourselves as helpful people, self-perception takes over and we continue to help.

The countries that have passed Good Samaritan laws realize the importance of self-interest: if people must pay fines or face jail sentences if they don’t help, then they are naturally more likely to help. And the programs in many schools, businesses, and other institutions that encourage students and workers to volunteer by rewarding them for doing so are also effective in increasing volunteering (Clary et al., 1998; Clary, Snyder, & Stukas, 1998).

Helping also occurs in part because of other-concern. We are more likely to help people we like and care about, we feel similar to, and with whom we experience positive emotions. Therefore, anything that we can do to increase our connections with others will likely increase helping. We must work to encourage ourselves, our friends, and our children to interact with others—to help them meet and accept new people and to instill a sense of community and caring in them. These social connections will make us feel closer to others and increase the likelihood we will help them. We must also work to install the appropriate norms in our children. Kids must be taught not to be selfish and to value the norms of sharing and altruism.

One way to increase our connection with others is to make those people highly salient and personal. The effectiveness of this strategy was vividly illustrated by a recent campaign by Sport Club Recife, a Brazilian football club, which promoted the idea of becoming an “immortal fan” of the club by registering as an organ donor (Carneiro, 2014). As a result of this campaign, in only the first year of the campaign, the waiting list for organ transplants in the city of Recife was reduced to zero. Similar campaigns are now being planned in France and Spain.

Another way to increase our connection with others is for charities to individualize the people they are asking us to help. When we see a single person suffering, we naturally feel strong emotional responses to that person. And, as we have seen, the emotions that we feel when others are in need are powerful determinants of helping. In fact, Paul Slovic (2007) found that people are simply unable to identify with statistical and abstract descriptions of need because they do not feel emotions for these victims in the same way they do for individuals. They argued that when people seem completely oblivious or numb to the needs of millions of people who are victims of earthquakes, genocide, and other atrocities, it is because the victims are presented as statistics rather than as individual cases. As Joseph Stalin, the Russian dictator who executed millions of Russians, put it, “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”

We can also use what we have learned about helping in emergency situations to increase the likelihood of responding. Most importantly, we must remember how strongly pluralistic ignorance can influence the interpretation of events and how quickly responsibility can be diffused among the people present at an emergency. Therefore, in emergency situations we must attempt to counteract pluralistic ignorance and diffusion of responsibility by remembering that others do not necessarily know more than we do. Depend on your own interpretation—don’t simply rely on your assumptions about what others are thinking and don’t just assume that others will do the helping.

We must be sure to follow the steps in Latané and Darley’s model, attempting to increase helping at each stage. We must make the emergency noticeable and clearly an emergency, for instance, by yelling out: “This is an emergency! Please call the police! I need help!” And we must attempt to avoid the diffusion of responsibility, for instance, by designating one individual to help: “You over there in the red shirt, please call 911 now!”

Key Takeaways

- Some people—for instance, those with altruistic personalities—are more helpful than others.

- Gender differences in helping depend on the type of helping that is required. Men are more likely to help in situations that involve physical strength, whereas women are more likely to help in situations that involve long-term nurturance and caring, particularly within close relationships.

- Our perception of the amount of the need is important. We tend to provide less help to people who seem to have brought on their own problems or who don’t seem to be working very hard to solve them on their own.

- In some cases, helping can create negative consequences. Dependency-oriented help may make the helped feel negative emotions, such as embarrassment and worry that they are seen as incompetent or dependent. Autonomy-oriented help is more easily accepted and will be more beneficial in the long run.

- Norms about helping vary across cultures, for instance, between Eastern and Western cultures.

- We can increase helping by using our theoretical knowledge about the factors that produce it. Our strategies can be based on using both self-concern and other-concern.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Visit the website and complete the online “Morality Test.” Write a brief reflection on the results of the test.

- Imagine that you knew someone who was ill and needed help. How would you frame your help to make him or her willing to accept it?

- Assume for a moment that you were in charge of creating an advertising campaign designed to increase people’s altruism. On the basis of your reading, what approaches might you take?

References

Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5–14.

Baron, J., & Miller, J. G. (2000). Limiting the scope of moral obligations to help: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(6), 703–725.

Batson, C. D., Oleson, K. C., Weeks, J. L., Healy, S. P., Reeves, P. J., Jennings, P., & Brown, T. (1989). Religious prosocial motivation: Is it altruistic or egoistic? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 873–884.

Becker, S. W., & Eagly, A. H. (2004). The heroism of women and men. American Psychologist, 59(3), 163–178.

Benson, P. L., Donahue, M. J., & Erickson, J. A. (Eds.). (1989). Adolescence and religion: A review of the literature from 1970 to 1986. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, 1, 153–181.

Bickman, L., & Kamzan, M. (1973). The effect of race and need on helping behavior. Journal of Social Psychology, 89(1), 73–77.

Blaine, B., Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1995). The unintended negative consequences of sympathy for the stigmatized. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(10), 889–905.

Borman, W. C., Penner, L. A., Allen, T. D., & Motowidlo, S. J. (2001). Personality predictors of citizenship performance. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1–2), 52–69.

Brickman, P. (1982). Models of helping and coping. American Psychologist, 37(4), 368–384.

Carneiro, J. (2014). How thousands of football fans are helping to save lives. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-27632527

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., & Stukas, A. (1998). Service-learning and psychology: Lessons from the psychology of volunteers’ motivations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530.

Davis, M. H., Luce, C., & Kraus, S. J. (1994). The heritability of characteristics associated with dispositional empathy. Journal of Personality, 62(3), 369–391.

DePaulo, B. M., Brown, P. L., Ishii, S., & Fisher, J. D. (1981). Help that works: The effects of aid on subsequent task performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(3), 478–487.

Dooley, P. A. (1995). Perceptions of the onset controllability of AIDS and helping judgments: An attributional analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(10), 858–869.

Eagly, A. H., & Becker, S. W. (2005). Comparing the heroism of women and men. American Psychologist, 60(4), 343–344.

Eisenberg, N., Guthrie, I. K., Murphy, B. C., Shepard, S. A., Cumberland, A., & Carlo, G. (1999). Consistency and development of prosocial dispositions: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 70(6), 1360–1372.

Furrow, J. L., King, P. E., & White, K. (2004). Religion and positive youth development: Identity, meaning, and prosocial concerns. Applied Developmental Science, 8(1), 17–26.

Grusec, J. E., Kuczynski, L., Rushton, J. P., & Simutis, Z. M. (1978). Modeling, direct instruction, and attributions: Effects on altruism. Developmental Psychology, 14(1), 51–57.

Holmes, J. G., Miller, D. T., & Lerner, M. J. (2002). Committing altruism under the cloak of self-interest: The exchange fiction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 144–151.

Kluegel, J. R., & Smith, E. R. (1986). Beliefs about inequality: Americans’ views of what is and what ought to be. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Kraut, R. E. (1973). Effects of social labeling on giving to charity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(6), 551–562.

Lerner, M. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York, NY: Plenum.

Mansfield, A. K., Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). “Why won’t he go to the doctor?”: The psychology of men’s help seeking.International Journal of Men’s Health, 2(2), 93–109.

Miller, J. G., Bersoff, D. M., & Harwood, R. L. (1990). Perceptions of social responsibilities in India and in the United States: Moral imperatives or personal decisions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), 33–47.

Morgan, S. P. (1983). A research note on religion and morality: Are religious people nice people? Social Forces, 61(3), 683–692.

Nadler, A. (2002). Inter-group helping relations as power relations: Maintaining or challenging social dominance between groups through helping. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 487–502.

Nadler, A. (Ed.). (1991). Help-seeking behavior: Psychological costs and instrumental benefits. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nadler, A., & Halabi, S. (2006). Intergroup helping as status relations: Effects of status stability, identification, and type of help on receptivity to high-status group’s help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(1), 97–110.

Nadler, A., Fisher, J. D., & Itzhak, S. B. (1983). With a little help from my friend: Effect of single or multiple act aid as a function of donor and task characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(2), 310–321.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671–686.

Penner, L. A. (2002). Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 447–467.

Penner, L. A., Fritzsche, B. A., Craiger, J. P., & Freifeld, T. S. (1995). Measuring the prosocial personality. In J. Butcher & C. Speigelberger (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 10, pp. 147–163). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Perlow, L., & Weeks, J. (2002). Who’s helping whom? Layers of culture and workplace behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(Spec. Issue), 345–361.

Ratner, R. K., & Miller, D. T. (2001). The norm of self-interest and its effects on social action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 5–16.

Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2007). God is watching you: Priming God concepts increases prosocial behavior in an anonymous economic game. Psychological Science, 18(9), 803–809.

Skitka, L. J. (1999). Ideological and attributional boundaries on public compassion: Reactions to individuals and communities affected by a natural disaster. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(7), 793–808.

Slovic, P. (2007). “If I look at the mass I will never act”: Psychic numbing and genocide. Judgment and Decision Making, 2(2), 79–95.

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (Eds.). (2004). Volunteers and volunteer organizations: Theoretical perspectives and practical concerns. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Snyder, M., Omoto, A. M., & Crain, A. L. (1999). Punished for their good deeds: Stigmatization of AIDS volunteers. American Behavioral Scientist, 42(7), 1175–1192.

Snyder, M., Omoto, A. M., & Lindsay, J. J. (Eds.). (2004). Sacrificing time and effort for the good of others: The benefits and costs of volunteerism. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- 4733 reads