Decision Making by a Jury

Although many countries rely on the decisions of judges in civil and criminal trials, the jury is the foundation of the legal system in many other nations. The notion of a trial by one’s peers is based on the assumption that average individuals can make informed and fair decisions when they work together in groups. But given all the problems facing groups, social psychologists and others frequently wonder whether juries are really the best way to make these important decisions and whether the particular composition of a jury influences the likely outcome of its deliberation (Lieberman, 2011).

As small working groups, juries have the potential to produce either good or poor decisions, depending on many of the factors that we have discussed in this chapter (Bornstein & Greene, 2011; Hastie, 1993; Winter & Robicheaux, 2011). And again, the ability of the jury to make a good decision is based on both person characteristics and group process. In terms of person variables, there is at least some evidence that the jury member characteristics do matter. For one, individuals who have already served on juries are more likely to be seen as experts, are more likely to be chosen as jury foreperson, and give more input during the deliberation (Stasser, Kerr, & Bray, 1982). It has also been found that status matters—jury members with higher-status occupations and education, males rather than females, and those who talk first are more likely be chosen as the foreperson, and these individuals also contribute more to the jury discussion (Stasser et al., 1982). And as in other small groups, a minority of the group members generally dominate the jury discussion (Hastie, Penrod, & Pennington, 1983), And there is frequently a tendency toward social loafing in the group (Najdowski, 2010). As a result, relevant information or opinions are likely to remain unshared because some individuals never or rarely participate in the discussion.

Perhaps the strongest evidence for the importance of member characteristics in the decision-making process concerns the selection of death-qualified juries in trials in which a potential sentence includes the death penalty. In order to be selected for such a jury, the potential members must indicate that they would, in principle, be willing to recommend the death penalty as a punishment. In some countries, potential jurors who indicate being opposed to the death penalty cannot serve on these juries. However, this selection process creates a potential bias because the individuals who say that they would not under any condition vote for the death penalty are also more likely to be rigid and punitive and thus more likely to find defendants guilty, a situation that increases the chances of a conviction for defendants (Ellsworth, 1993).

Although there are at least some member characteristics that have an influence upon jury decision making, group process, as in other working groups, plays a more important role in the outcome of jury decisions than do member characteristics. Like any group, juries develop their own individual norms, and these norms can have a profound impact on how they reach their decisions. Analysis of group process within juries shows that different juries take very different approaches to reaching a verdict. Some spend a lot of time in initial planning, whereas others immediately jump right into the deliberation. And some juries base their discussion around a review and reorganization of the evidence, waiting to take a vote until it has all been considered, whereas other juries first determine which decision is preferred in the group by taking a poll and then (if the first vote does not lead to a final verdict) organize their discussion around these opinions. These two approaches are used about equally often but may in some cases lead to different decisions (Hastie, 2008).

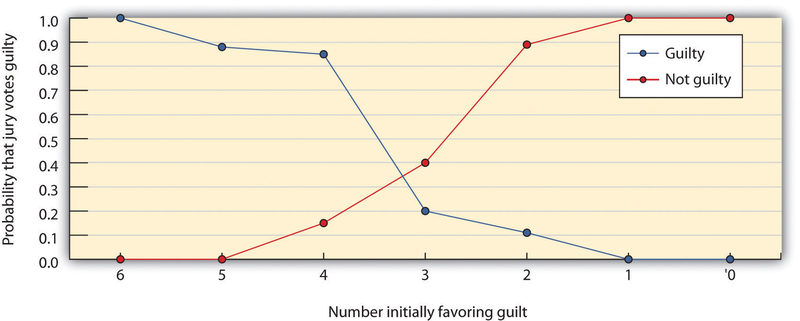

Perhaps most important, conformity pressures have a strong impact on jury decision making. As you can see in Figure 10.12, when there are a greater number of jury members who hold the majority position, it becomes more and more certain that their opinion will prevail during the discussion. This is not to say that minorities cannot ever be persuasive, but it is very difficult for them. The strong influence of the majority is probably due to both informational conformity (i.e., that there are more arguments supporting the favored position) and normative conformity (people are less likely to want to be seen as disagreeing with the majority opinion).

This figure shows the decisions of six-member mock juries that made “majority rules” decisions. When the majority of the six initially favored voting guilty, the jury almost always voted guilty, and when the majority of the six initially favored voting innocent, the jury almost always voted innocence. The juries were frequently hung (could not make a decision) when the initial split was three to three. Data are from Stasser, Kerr, and Bray (1982).

Research has also found that juries that are evenly split (three to three or six to six) tend to show a leniency bias by voting toward acquittal more often than they vote toward guilt, all other factors being equal (MacCoun & Kerr, 1988). This is in part because juries are usually instructed to assume innocence unless there is sufficient evidence to confirm guilt—they must apply a burden of proof of guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” The leniency bias in juries does not always occur, although it is more likely to occur when the potential penalty is more severe (Devine et al., 2004; Kerr, 1978).

Given what you now know about the potential difficulties that groups face in making good decisions, you might be worried that the verdicts rendered by juries may not be particularly effective, accurate, or fair. However, despite these concerns, the evidence suggests that juries may not do as badly as we would expect. The deliberation process seems to cancel out many individual juror biases, and the importance of the decision leads the jury members to carefully consider the evidence itself.

Key Takeaways

- Under certain situations, groups can show significant process gains in regards to decision making, compared with individuals. However, there are a number of social forces that can hinder effective group decision making, which can sometimes lead groups to show process losses.

- Some group process losses are the result of groupthink—when a group, as result of a flawed group process and strong conformity pressures, makes a poor judgment.

- Process losses may result from the tendency for groups to discuss information that all members have access to while ignoring equally important information that is available to only a few of the members.

- Brainstorming is a technique designed to foster creativity in a group. Although brainstorming often leads to group process losses, alternative approaches, including the use of group support systems, may be more effective.

- Group decisions can also be influenced by group polarization—when the attitudes held by the individual group members become more extreme than they were before the group began discussing the topic.

- Understanding group processes can help us better understand the factors that lead juries to make better or worse decisions.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Consider a time when a group that you belonged to experienced a process gain, and another time showed a process loss in terms of decision making. Which of the factors discussed in this section do you think help to explain these two different outcomes?

- Describe a current social or political issue where you have seen groupthink in action. What features of groupthink outlined in this section were particularly evident? When in your own life have you been in a group situation where groupthink was evident? What decision was reached and what was the outcome for you?

- When have you been in a group that has not shared information effectively? Why do you think that this happened and what were the consequences?

- Outline two situations, one when you were in a group that used brainstorming and you feel that it was helpful to the group decision-making process, and another when you think it was a hindrance. Why do you think the brainstorming had these opposite effects on the groups in the two situations?

- What examples of group polarization have you seen in the media recently? How well do the ideas of normative and informational conformity explain why polarization occurred in these situations? What other factors might also have been at work?

- If you or someone you knew had a choice to be tried by either a judge or a jury, taking into account the research in this section, which would you choose, and why?

References

Abrams, D., Wetherell, M., Cochrane, S., & Hogg, M. (1990). Knowing what to think by knowing who you are: Self-categorization and the nature of norm formation, conformity, and group polarization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 97–119.

Baron, R. S. (2005). So right it’s wrong: Groupthink and the ubiquitous nature of polarized group decision making. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 37, pp. 219–253). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Bornstein, B. H., & Greene, E. (2011). Jury decision making: Implications for and from psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(1), 63–67.

Brauer, M., Judd, C. M., & Gliner, M. D. (2006). The effects of repeated expressions on attitude polarization during group discussions. In J. M. Levine & R. L. Moreland (Eds.), Small groups (pp. 265–287). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Cheng, P.-Y., & Chiou, W.-B. (2008). Framing effects in group investment decision making: Role of group polarization. Psychological Reports, 102(1), 283–292.

Clark, R. D., Crockett, W. H., & Archer, R. L. (1971). Risk-as-value hypothesis: The relationship between perception of self, others, and the risky shift. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 20, 425–429.

Clayton, M. J. (1997). Delphi: A technique to harness expert opinion for critical decision-making tasks in education. Educational Psychology, 17(4), 373–386. doi: 10.1080/0144341970170401.

Collaros, P. A., & Anderson, I. R. (1969). Effect of perceived expertness upon creativity of members of brainstorming groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 53, 159–163.

Connolly, T., Routhieaux, R. L., & Schneider, S. K. (1993). On the effectiveness of group brainstorming: Test of one underlying cognitive mechanism. Small Group Research, 24(4), 490–503.

Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., & Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and delphi processes. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Dennis, A. R., & Valacich, J. S. (1993). Computer brainstorms: More heads are better than one. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 531–537.

Devine, D. J., Olafson, K. M., Jarvis, L. L., Bott, J. P., Clayton, L. D., & Wolfe, J. M. T. (2004). Explaining jury verdicts: Is leniency bias for real? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2069–2098.

Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1987). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 497–509.

Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1991). Productivity loss in idea-generating groups: Tracking down the blocking effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 392–403.

Drummond, J. T. (2002). From the Northwest Imperative to global jihad: Social psychological aspects of the construction of the enemy, political violence, and terror. In C. E. Stout (Ed.), The psychology of terrorism: A public understanding (Vol. 1, pp. 49–95). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Ellsworth, P. C. (1993). Some steps between attitudes and verdicts. In R. Hastie (Ed.), Inside the juror: The psychology of juror decision making. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Faulmüller, N., Kerschreiter, R., Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Beyond group-level explanations for the failure of groups to solve hidden profiles: The individual preference effect revisited. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13(5), 653–671.

Forsyth, D. (2010). Group dynamics (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Gallupe, R. B., Cooper, W. H., Grise, M.-L., & Bastianutti, L. M. (1994). Blocking electronic brainstorms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 77–86.

Hastie, R. (1993). Inside the juror: The psychology of juror decision making. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hastie, R. (2008). What’s the story? Explanations and narratives in civil jury decisions. In B. H. Bornstein, R. L. Wiener, R. Schopp, & S. L. Willborn (Eds.), Civil juries and civil justice: Psychological and legal perspectives (pp. 23–34). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Hastie, R., Penrod, S. D., & Pennington, N. (1983). Inside the jury. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hinsz, V. B. (1990). Cognitive and consensus processes in group recognition memory performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 705–718.

Hogg, M. A., Turner, J. C., & Davidson, B. (1990). Polarized norms and social frames of reference: A test of the self-categorization theory of group polarization. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 11(1), 77–100.

Hornsby, J. S., Smith, B. N., & Gupta, J. N. D. (1994). The impact of decision-making methodology on job evaluation outcomes: A look at three consensus approaches. Group and Organization Management, 19(1), 112–128.

Janis, I. L. (2007). Groupthink. In R. P. Vecchio (Ed.), Leadership: Understanding the dynamics of power and influence in organizations (2nd ed., pp. 157–169). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Johnson, D.W., & Johnson, F.P. (2012). Joining together – group theory and group skills (11th ed). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Kerr, N. L. (1978). Severity of prescribed penalty and mock jurors’ verdicts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(12), 1431–1442.

Kogan, N., & Wallach, M. A. (1967). Risky-shift phenomenon in small decision-making groups: A test of the information-exchange hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3, 75–84.

Kramer, R. M. (1998). Revisiting the Bay of Pigs and Vietnam decisions 25 years later: How well has the groupthink hypothesis stood the test of time? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73(2–3), 236–271.

Kroon, M. B., Van Kreveld, D., & Rabbie, J. M. (1992). Group versus individual decision making: Effects of accountability and gender on groupthink. Small Group Research, 23(4), 427-458.

Larson, J. R. J., Foster-Fishman, P. G., & Keys, C. B. (1994). The discussion of shared and unshared information in decision-making groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 446–461.

Lieberman, J. D. (2011). The utility of scientific jury selection: Still murky after 30 years. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(1), 48–52.

MacCoun, R. J., & Kerr, N. L. (1988). Asymmetric influence in mock jury deliberation: Jurors’ bias for leniency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 21–33.

Mackie, D. M. (1986). Social identification effects in group polarization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 720–728.

Mackie, D. M., & Cooper, J. (1984). Attitude polarization: Effects of group membership.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, u575–585.

Matusitz, J., & Breen, G. (2012). An examination of pack journalism as a form of groupthink: A theoretical and qualitative analysis. Journal Of Human Behavior In The Social Environment, 22 (7), 896-915.

McCauley, C. R. (1989). Terrorist individuals and terrorist groups: The normal psychology of extreme behavior. In J. Groebel & J. H. Goldstein (Eds.), Terrorism: Psychological perspectives (p. 45). Sevilla, Spain: Universidad de Sevilla.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., DeChurch, L. A., Jimenez-Rodriguez, M., Wildman, J., & Shuffler, M. (2011). A meta-analytic investigation of virtuality and information sharing in teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 214–225.

Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Knowing others’ preferences degrades the quality of group decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(5), 794–808.

Morrow, K. A., & Deidan, C. T. (1992). Bias in the counseling process: How to recognize and avoid it. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 571-577.

Myers, D. G. (1982). Polarizing effects of social interaction. In H. Brandstatter, J. H. Davis, & G. Stocher-Kreichgauer (Eds.), Contemporary problems in group decision-making (pp. 125–161). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Myers, D. G., & Bishop, G. D. (1970). Discussion effects on racial attitudes. Science, 169(3947), 778–779. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3947.778

Myers, D. G., & Kaplan, M. F. (1976). Group-induced polarization in simulated juries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2(1), 63–66.

Najdowski, C. J. (2010). Jurors and social loafing: Factors that reduce participation during jury deliberations. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 28(2), 39–64.

Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination. Oxford, England: Scribner’s.

Paulus, P. B., & Dzindolet, M. T. (1993). Social influence processes in group brainstorming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 575–586.

Redding, R. E. (2012). Likes attract: The sociopolitical groupthink of (social) psychologists. Perspectives On Psychological Science, 7 (5), 512-515.

Reimer, T., Reimer, A., & Czienskowski, U. (2010). Decision-making groups attenuate the discussion bias in favor of shared information: A meta-analysis. Communication Monographs, 77(1), 121–142.

Reimer, T., Reimer, A., & Hinsz, V. B. (2010). Naïve groups can solve the hidden-profile problem. Human Communication Research, 36(3), 443–467.

Siau, K. L. (1995). Group creativity and technology. Psychosomatics, 31, 301–312.

Stasser, G., Kerr, N. L., & Bray, R. M. (1982). The social psychology of jury deliberations: Structure, process and product. In N. L. Kerr & R. M. Bray (Eds.), The psychology of the courtroom(pp. 221–256). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Stasser, G., & Stewart, D. (1992). Discovery of hidden profiles by decision-making groups: Solving a problem versus making a judgment. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 63, 426–434.

Stasser, G., & Taylor, L. A. (1991). Speaking turns in face-to-face discussions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60,675–684.

Stasser, G., Taylor, L. A., & Hanna, C. (1989). Information sampling in structured and unstructured discussions of three- and six-person groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(1), 67–78.

Stasser, G., & Titus, W. (1985). Pooling of unshared information in group decision making: Biased information sampling during discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 1467–1478.

Stein, M. I. (1978). Methods to stimulate creative thinking. Psychiatric Annals, 8(3), 65–75.

Stoner, J. A. (1968). Risky and cautious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4, 442–459.

Stroebe, W., & Diehl, M. (1994). Why groups are less effective than their members: On productivity losses in idea-generating groups. European Review of Social Psychology, 5, 271–303.

Valacich, J. S., Jessup, L. M., Dennis, A. R., & Nunamaker, J. F. (1992). A conceptual framework of anonymity in group support systems. Group Decision and Negotiation, 1(3), 219–241.

Van Swol, L. M. (2009). Extreme members and group polarization. Social Influence, 4(3), 185–199.

Vinokur, A., & Burnstein, E. (1978). Novel argumentation and attitude change: The case of polarization following group discussion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 8(3), 335–348.

Watson, G. (1931). Do groups think more effectively than individuals? In G. Murphy & L. Murphy (Eds.), Experimental social psychology. New York: Harper.

Winter, R. J., & Robicheaux, T. (2011). Questions about the jury: What trial consultants should know about jury decision making. In R. L. Wiener & B. H. Bornstein (Eds.), Handbook of trial consulting (pp. 63–91). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Wittenbaum, G. M. (1998). Information sampling in decision-making groups: The impact of members’ task-relevant status. Small Group Research, 29(1), 57–84.

Zhu, H. (2010). Group polarization on corporate boards: Theory and evidence on board decisions about acquisition premiums, executive compensation, and diversification. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Ziller, R. (1957). Group size: A determinant of the quality and stability of group decision. Sociometry, 20, 165-173.

- 5251 reads