In his important research on group perceptions, Henri Tajfel and his colleagues (Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971) demonstrated how incredibly powerful the role of self-concern is in group perceptions. He found that just dividing people into arbitrary groups produces ingroup favoritism—the tendency to respond more positively to people from our ingroups than we do to people from outgroups.

In Tajfel’s research, small groups of high school students came to his laboratory for a study supposedly concerning “artistic tastes.” The students were first shown a series of paintings by two contemporary artists, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. Supposedly on the basis of their preferences for each painting, the students were divided into two groups (they were called the X group and the Y group). Each boy was told which group he had been assigned to and that different boys were assigned to different groups. But none of them were told the group memberships of any of the other boys.

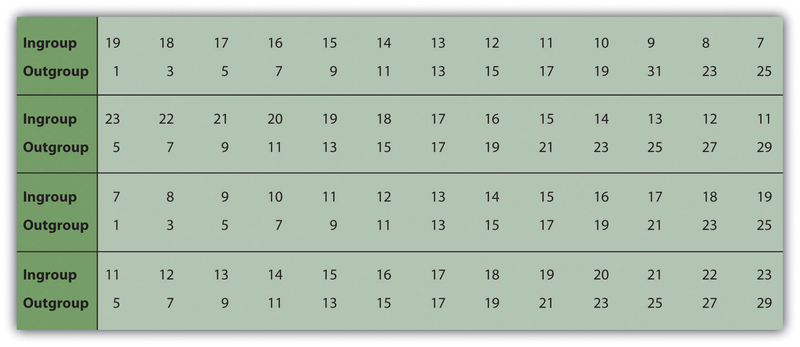

The boys were then given a chance to allocate points to other boys in their own group and to boys in the other group (but never to themselves) using a series of payoff matrices, such as those shown in Figure 11.8. The charts divided a given number of rewards between two boys, and the boys thought that the rewards would be used to determine how much each boy would be paid for his participation. In some cases, the division was between two boys in the boy’s own group (the ingroup); in other cases, the division was between two boys who had been assigned to the other group (the outgroup); and in still other cases, the division was between a boy in the ingroup and a boy in the outgroup. Tajfel then examined the goals that the boys used when they divided up the points.

A comparison of the boys’ choices in the different matrices showed that they allocated points between two boys in the ingroup or between two boys in the outgroup in an essentially fair way, so that each boy got the same amount. However, fairness was not the predominant approach when dividing points between ingroup and outgroup. In this case, rather than exhibiting fairness, the boys displayed ingroup favoritism, such that they gave more points to other members of their own group in relationship to boys in the other group. For instance, the boys might assign 8 points to the ingroup boy and only 3 points to the outgroup boy, even though the matrix also contained a choice in which they could give the ingroup and the outgroup boys 13 points each. In short, the boys preferred to maximize the gains of the other boys in their own group in comparison with the boys in the outgroup, even if doing so meant giving their own group members fewer points than they could otherwise have received.

Perhaps the most striking part of Tajfel’s results is that ingroup favoritism was found to occur on the basis of such arbitrary and unimportant groupings. In fact, ingroup favoritism occurs even when the assignment to groups is on such trivial things as whether people “overestimate” or “underestimate” the number of dots shown on a display, or on the basis of a completely random coin toss (Billig & Tajfel, 1973; Locksley, Ortiz, & Hepburn, 1980). Tajfel’s research, as well other research demonstrating ingroup favoritism, provides a powerful demonstration of a very important social psychological process: groups exist simply because individuals perceive those groups as existing. Even in a case where there really is no group (at least no meaningful group in any real sense), we still perceive groups and still demonstrate ingroup favoritism.

- 3425 reads