If someone were to ask you who you might end up marrying (assuming you are not married already and would like to get married), they would guess that you’d respond with a list of perhaps the preferred personality traits or an image of your desired mate. You’d probably say something about being attractive, rich, creative, fun, caring, and so forth. And there is no question that such individual characteristics matter. But social psychologists realize that there are other aspects that are perhaps even more important. Consider this:

You’ll never marry someone whom you never meet!

Although that seems obvious, it’s also really important. There are about 7 billion people in the world, and you are only going to have the opportunity to meet a tiny fraction of those people before you marry. This also means that you are likely to marry someone who’s pretty similar to you because, unless you travel widely, most of the people you meet are going to share at least part of your cultural background and therefore have some of the values that you hold. In fact, the person you marry probably will live in the same city as you, attend the same school, take similar classes, work in a similar job and be similar to you in other respects (Kubitschek & Hallinan, 1998).

Although meeting someone is an essential first step, simply being around another person also increases liking. People tend to become better acquainted with, and more fond of, each other when the social situation brings them into repeated contact, which is the basic principle of proximity liking. For instance, research has found that students who sit next to each other in class are more likely to become friends, and this is true even when the seating is assigned by the instructor (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008). Festinger, Schachter, and Back (1950) studied friendship formation in people who had recently moved into a large housing complex. They found not only that people became friends with those who lived near them but that people who lived nearer the mailboxes and at the foot of the stairway in the building (where they were more likely to come into contact with others) were able to make more friends than those who lived at the ends of the corridors in the building and thus had fewer social encounters with others.

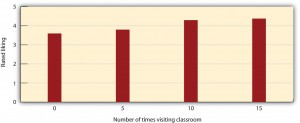

The mere exposure effect refers to the tendency to prefer stimuli (including, but not limited to, people) that we have seen frequently. Consider the research findings presented in Figure 7.5. In this study, Moreland and Beach (1992) had female confederates attend a large lecture class of over 100 students 5, 10, or 15 times or not at all during a semester. At the end of the term, the students were shown pictures of the confederates and asked to indicate if they recognized them and also how much they liked them. The number of times the confederates had attended class didn’t influence the other students’ recognition of them, but it did influence their liking for them. As predicted by the mere-exposure hypothesis, students who had attended more often were liked more.

Richard Moreland and Scott Beach had female confederates visit a class 5, 10, or 15 times or not at all over the course of a semester. Then the students rated their liking of the confederates. The mere exposure effect is clear. Data are from Moreland and Beach (1992).

The effect of mere exposure is powerful and occurs in a wide variety of situations (Bornstein, 1989). Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at someone they are seeing for the first time (Brooks-Gunn & Lewis, 1981). And people have been found to prefer left-to-right reversed images of their own face over their normal (nonreversed) face, whereas their friends prefer their regular face over the reversed one (Mita, Dermer, & Knight, 1977). This also is expected on the basis of mere exposure, since people see their own faces primarily in mirrors and thus are exposed to the reversed face more often.

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an initial and potentially protective fear of the unknown, but as things become more familiar, they produce more positive feelings and seem safer (Freitas, Azizian, Travers, & Berry, 2005; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001). When the stimuli are people, there may well be an added effect—familiar people are more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them even more. Leslie Zebrowitz and her colleagues showed that we like people of our own race in part because they are perceived as familiar to us (Zebrowitz, Bronstad, & Lee, 2007).

Keep in mind that mere exposure applies only to the change that occurs when one is completely unfamiliar with another person (or object) and subsequently becomes more familiar with him or her. Thus mere exposure applies only in the early stages of attraction. Later, when we are more familiar with someone, that person may become too familiar and thus boring. You may have experienced this effect when you first bought some new songs and began to listen to them. Perhaps you didn’t really like all the songs at first, but you found yourself liking them more and more as you played them more often. If this has happened to you, you have experienced mere exposure. But perhaps one day you discovered that you were really tired of the songs—they had become too familiar. You put the songs away for a while, only bringing them out later, when you found that liked them more again (they were now less familiar). People prefer things that have an optimal level of familiarity—neither too strange nor too well known (Bornstein, 1989).

- 4628 reads