Management can take any or all of five actions in implementing a job design program Exhibit 23. First, managers can combine tasks. Banquet waiters who, as part of a group, were responsible for setting up only the entree knife at each place for a banquet of 500 can be given the task of setting up the entire dinner setting for a smaller number of guests. The more tasks given the waiter, the more skills are required. Additionally, the waiter is able to identify more readily with the finished banquet setting, improving task identity.

Second, managers can form natural work units. The central idea is to establish in an employee's mind a sense of ownership over the job. This occurs when room attendants are assigned a specific floor of their own rather than getting rooms that are randomly assigned. It also happens when a hotel has three airport shuttle buses and each driver is assigned responsibility for a particular bus. When this happens, task identity and task significance both increase. The room attendant sees the results of his or her work every day and can be proud of a specific floor; the driver knows that the way the bus is handled today will affect him or her tomorrow because the driver will be using the same vehicle.

Third, managers can enrich back-of-the-house jobs by bringing out front employees who ordinarily would not come in contact with guests. For example, the server acts as an effective buffer between the chef and the customer. Occasionally bringing the chef out front affects three core job dimensions. It requires the use of an additional skill: dealing with people. It can increase autonomy, for example, if the chef is given responsibility for handling customers' complaints, perhaps by being allowed to issue a complimentary meal check if something is wrong with the food. It also improves feedback from customer to employee on the quality of the food.

Fourth, managers can vertically load jobs. Vertical loading refers to the idea of passing on to the employee some of the traditional management functions of planning and control. This is the single most crucial principle of job redesign. There are various ways to implement this. The employee doing the job may be given more discretion for setting work schedules, choosing how to do the job, checking on quality, or training other people to perform the job. Additional authority can be granted to employees. Discretion may be given over when to take breaks. Employees can be encouraged to develop solutions to problems rather than bring every concern to a supervisor. Workers can be given more information about the finances of the business. Many employees overestimate the profits a hotel or restaurant obtains; letting them know the costs involved in wastage and breakage and the thin margin the property exists on makes them feel more involved as well as more cost-conscious.

Take the position of room attendant. Typically, the attendant cleans the room; then a supervisor comes around to inspect that room, using a checklist. The incomplete items are noted and given to the attendant. The room attendant is shielded from taking responsibility; the supervisor, after all, will find any mistakes. But if we give the checklist to the room attendant and have the person doing the job also double-check whether it has been done properly, we are vertically loading the job. This does not mean the room inspections need never be done. But it places more responsibility on the shoulders of the person performing the task, which can increase the worker's motivation and satisfaction. It may also be more satisfying to let this person take a break when it seems appropriate to him or her (subject to the necessity of serving the guests, of course) rather than according to the whim of the supervisor, and also to tell the employee such relevant information as how much a torn sheet costs to replace.

All of these examples of vertical loading affect the extent to which the worker experiences responsibility for the outcome of the job.

The fifth major action management can take to implement job design is to open up channels of communication. Employees want to know how they are performing. This means more than keeping an open-door policy. It means touring the property several times a day to see what is going on and to compliment and coach where necessary. The best kind of feedback comes from the work itself, however, rather than a wait for what management may or may not notice. The tips at the end of a busy shift represent feedback; the night audit that balances also represents feedback. Often the supervisor corrects mistakes without informing the employee because the order has to go out immediately or the employee has gone home at the end of a shift. But this does a disservice to the worker as well as harms future job performance. Without feedback, the employee does not have a chance to improve, thinks that he or she has done a good job, and is likely to repeat the same error.

Leadership style

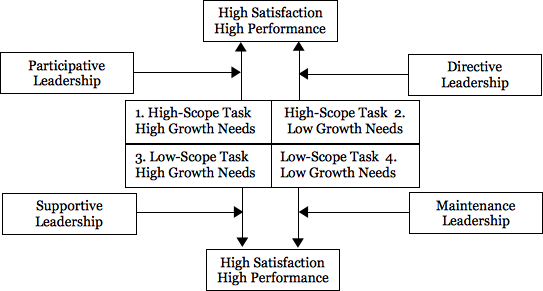

Managers also can affect employee job satisfaction and performance through the style of leadership they adopt. A model showing how leadership style relates to the scope of the job and the growth needs of the employee is depicted in Exhibit 24.

This model assumes that appropriate leadership style is dependent on the interaction of the employee's growth needs and the scope of the job being performed. When an employee has high growth needs and is performing a job high in variety, or a high-scope job, autonomy and participative management would be appropriate (box 1).

When a job is varied but the employee does not want to cope with it (box 2), the manager should provide direction in planning, organizing, and controlling the work of the employee.

When an employee with high growth needs is performing a task that is unfulfilling (box 3), frustration and dissatisfaction will probably result. Supportive leadership will be necessary to produce a satisfied and productive employee.

An employee with low growth needs might be performing a task that is rather dull and repetitive (box 4). In this case, supportive leadership is unnecessary because the employee is unlikely to be frustrated. The most appropriate style is a form of minimum interference, in which performance is monitored but the manager does not closely supervise the employee. As long as the job is being performed to the level required, little or no interaction between manager and employee is needed. This maintenance leadership behavior may be appropriate unless and until performance or satisfaction problems arose, in which case more direction or support would be given.

Limited research has been conducted on this model. For the most part, no causal relationship has been proven between leadership behavior and productivity. It may exist, but researchers have as yet been unable to prove it. The only situation in which such a relationship has been found is when an employee with low growth needs is performing a job that is low in variety, autonomy and feedback. In this case, maintenance leadership (box 4) has produced more productivity. In all likelihood, the factors affecting productivity are more varied than the two suggested here; this may account for the lack of evidence about the model.

It appears there is less a manager can do to affect job satisfaction when there is a match between employee growth needs and job scope. When an employee high in growth needs is performing a job high in scope (box 1) or an employee with little desire for an enriched job is performing a task low in scope (box 4), satisfaction with the job appears unrelated to management style. Leadership style can and does seem to make more of a difference in the other two cases (boxes 2 and 3), along the lines suggested.

Management of symbols

So far, this chapter has assumed a link between objective job characteristics and employee satisfaction and productivity. However, individual behavior is a function of that individual's perception of a situation. Adding more tasks to a job will have no impact on the employee unless that person perceives that the job has been enriched. Managers can influence the way employees perceive their jobs through a variety of symbols. The symbols used cannot and will not substitute for substance. Calling a cleaner a maintenance engineer will have little or no positive impact on the employee if the change in job title is not accompanied by substantive changes in job assignments and rewards. On the other hand, changes in a job can be ineffective if management continues to give the employee the impression that the job is unimportant.

The words management uses, the way management chooses to spend time, and the settings chosen for various activities all can influence employee perceptions.

The language used can tell an employee how management perceives the job. Job descriptions that indicate routine duties and close supervision paint a negative picture to the employee. Of course, in some cases the employee is not given a written job description. When an employee is told to "follow" another employee for two days, and that is the sum total of the "training", the impression is that the job is not very taxing, requires little preparation or knowledge, and therefore is of little importance. That means the person performing the job is not considered very important. The Disney organization, on the other hand, calls its employees "cast members", talks about being "on stage", and stresses the importance of every position in the words and actions used. Contrast that with the food and beverage manager who wonders aloud to the dishwasher: "I don't know how you can stand this for eight hours a day." Many phrases can convey management's negative perception of a task:

- "I hate to ask you to do this, but..."

- "All you have to do is..."

- "Would you mind..."

Language is also used to describe the level of skill required for the job. Describing a position as unskilled or semiskilled has the same negative effect. It can help in the orientation process to let employees know the history and tradition of the job they are performing. Innkeepers have a long and rich tradition of providing refuge for the weary traveler; servers have long been regarded as artisans in Europe. Disney has each of its employees take a course entitled Traditions 1. This course starts with Steamboat Willie, the original Mickey Mouse cartoon, and ends with EPCOT (the Experimental Prototype City of Tomorrow). Employees see where the organization has come from and where they fit best.

If restaurant employees are told: "You start as a hostess and, if you work out and when we get an opening, we'll move you into a server's position", they learn that we do not think much of the hostess position. It is better if they are told: "We have found that you will benefit from starting out in this position. You will have a chance to work with all of our servers and see how this operation works. You set the tone for the customer's experience because you make that first impression. When you get your own station, you'll have a better understanding of the way the restaurant operates."

A story is told of two stonemasons working on a project. When asked what they were doing, the first answered: "I'm smoothing this stone"; the second said: "I'm building a cathedral." Who do you think was more motivated?

Managers can impress on all employees the important role each one plays in ensuring that a special dinner celebration is successful for a customer or that a vacation a family has saved for all year is enjoyed. In part, the quality of tools, supplies and materials used is also a symbol of how important we consider a job. Attempts to shave costs by providing cheap substitutes for quality reflect on the importance of the job and, therefore, the person performing that job. An operator is not merely washing dishes; he or she is responsible for a piece of valuable equipment. Let them know.

Language also can be used to tell employees how important their job is to the profits of the hotel or restaurant. Take those who burnish the silverware up to see the banquet room when it is set up for a party. Let them see and know in words how important the job that they do is to the look of the room and how tarnished silverware can take away from the enjoyment of the meal.

Management actions also can influence employee perceptions. What managers do reflects what they consider important. The manager who does not spend time in the back of the house tells kitchen employees their jobs are less important. Managers should notice the little things employees do that make the difference between doing or not doing a job well. It is also important to know when to step in to assist.

Management also can influence employee perceptions through the work setting chosen. At the employee dining area of the Bank of England in London, the dish-washing section is placed on the third floor in a well-ventilated, brightly painted large room with a view. The effect on the employees, who are used to being sequestered in the dingy basement of a restaurant, is dramatic.

The place chosen for employee meetings can affect the way in which employees view the importance of the topic under discussion. A meeting held in the comfort of a meeting room normally used for guest business will have more attention than one held in the employees' quarters.

Symbols cannot be a substitute for substance. However, a program of job design can be made ineffective unless management ensures that positive signals about the employees' jobs are given them through management words and actions.

- 3110 reads