There are many ways to organize new information that are especially well-suited to teacher-directed instruction. A common way is simply to ask students to outline information read in a text or heard in a lecture. Outlining works especially well when the information is already organized somewhat hierarchically into a series of main topics, each with supporting subtopics or subpoints. Outlining is basically a form of the more general strategy of taking notes, or writing down key ideas and terms from a reading or lecture. Research studies find that that the precise style or content of notes is less important that the quantity of notes taken: more detail is usually better than less (Ward & Tatsukawa, 2003). Written notes insure that a student thinks about the material not only while writing it down, but also when reading the notes later. These benefits are especially helpful when students are relatively inexperienced at school learning in general (as in the earlier grade levels), or relatively inexperienced about a specific topic or content in particular. Not surprisingly, such students may also need more guidance than usual about what and how to write notes. It can be helpful for the teacher to provide a note-taking guide, like the ones shown in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 9.1: Two note taking guides

9.2: Notes on Science Experiment

- Purpose of the experiment (in one sentence):

- Equipment needed (list each item and define any special terms):

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- Procedure used (be specific!):

- __________________

- Results (include each measurement, rounded to the nearest integer):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9.3: Guide to Notes About Tale of Two Cities:

- Main characters (list and describe in just a few words):

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- Setting of the story (time and place):

- Unfamiliar vocabulary in the story (list and define):

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- Plot (write down only the main events):

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- __________________

- Theme (or underlying “message”) of the story:

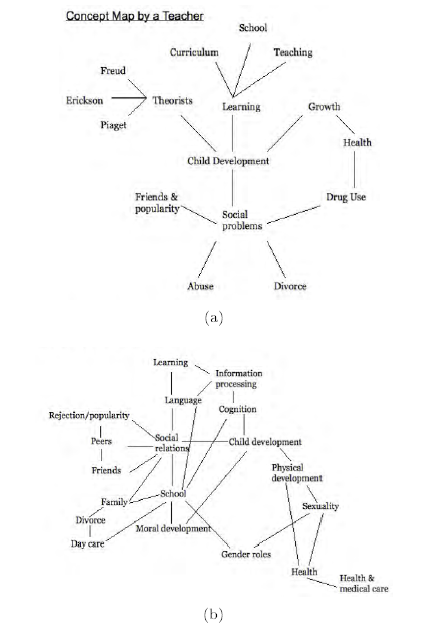

In learning expository material, another helpful strategy one that is more visually oriented is to make concept maps, or diagrams of the connections among concepts or ideas. Exhibit 5 shows concept maps made by two individuals that graphically depict how a key idea, child development, relates to learning and education. One of the maps was drawn by a classroom teacher and the other by a university professor of psychology (Seifert, 1991). They suggest possible differences in how the two individuals think about children and their development. Not surprisingly, the teacher gave more prominence to practical concerns (for example, classroom learning and child abuse), and the professor gave more prominence to theoretical ones (for example, Erik Erikson and Piaget). The differences suggest that these two people may have something different in mind when they use the same term, child development. The differences have the potential to create misunderstandings between them (Seifert, 1999; Super & Harkness, 2003). By the same token, the two maps also suggest what each person might need to learn in order to achieve better understanding of the other person's thinking and ideas.

- 2778 reads