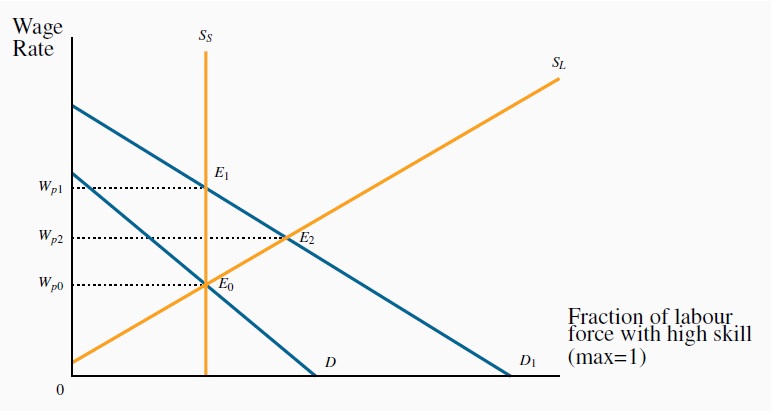

Individuals with different education levels earn different wages. The education premium is the difference in earnings between the more and less highly educated. Consider Figure 13.2 which contains supply and demand functions with a twist. We imagine that there are two types of labour: one with a high level of human capital, the other with a lower level. The vertical axis measures the wage premium of the high-education group, and the horizontal axis measures the fraction of the total labour force that is of the high-skill type. D is the relative demand for the high skill workers. It defines the premium that demanders are willing to pay to the higher skill group, depending upon the makeup of their work force: for example, if they were to employ all or virtually all high-skill workers, they would be willing to pay a smaller premium than if they were to employ a small fraction of high-skill and a large fraction of low-skill workers.

A shift in demand increases the wage premium in the short run from Eo to E by more than in the long run (to E

by more than in the long run (to E ). In the short run, the percentage of the labour force (SS) that is highly skilled is fixed. In the long run the labour force

(

). In the short run, the percentage of the labour force (SS) that is highly skilled is fixed. In the long run the labour force

( ) is variable and responds to the wage premium.

) is variable and responds to the wage premium.

Education premium: the difference in earnings

between the more and less highly educated.

Education premium: the difference in earnings

between the more and less highly educated.

In the short run the make-up of the labour force is fixed, and this is reflected in the vertical supply curve Ss. The equilibrium is at Eo, and  is the premium, or excess, paid to the higher-skill worker over the lower-skill worker.

In the long run it is possible for the economy to change the composition of its labour supply: if the wage premium increases, more individuals will find it profitable to train as high-skill

workers. That is to say, the fraction of the total that is high skill increases. It follows that the long run supply curve slopes upwards.

is the premium, or excess, paid to the higher-skill worker over the lower-skill worker.

In the long run it is possible for the economy to change the composition of its labour supply: if the wage premium increases, more individuals will find it profitable to train as high-skill

workers. That is to say, the fraction of the total that is high skill increases. It follows that the long run supply curve slopes upwards.

So what happens when there is an increase in the demand for high-skill workers relative to lowskill workers? The demand curve shifts upward to  , and the new equilibrium is at

, and the new equilibrium is at  . The supply mix is fixed in the short run. But over time, some individuals who might have been just indifferent between

educating themselves more and going into the market place with lower skill levels now find it worthwhile to pursue further education. The higher anticipated returns to the additional human

capital now exceed the additional costs of more schooling, whereas before the premium increase these additional costs and benefits were in balance. In Figure 13.2 the new shortrun equilibrium at

. The supply mix is fixed in the short run. But over time, some individuals who might have been just indifferent between

educating themselves more and going into the market place with lower skill levels now find it worthwhile to pursue further education. The higher anticipated returns to the additional human

capital now exceed the additional costs of more schooling, whereas before the premium increase these additional costs and benefits were in balance. In Figure 13.2 the new shortrun equilibrium at  , has a corresponding wage premium of

, has a corresponding wage premium of . In the long run, after additional supply has reached the market, the increased premium

is moderated to

. In the long run, after additional supply has reached the market, the increased premium

is moderated to at the equilibrium

at the equilibrium  .

.

Application Box: How big is the education premium?

Many studies have attempted to compute the earnings value of additional education in Canada beyond a completed high-school diploma. A typical finding is that a completed university bachelorâ˘AZ´s degree generates an additional 40% in earnings for men on average in the modern era and perhaps even more for women. Individuals who do not complete high school earn at least 10% less than high school graduates. The picture in the US economy is broadly similar; the education premium has been rising there for several decades. The education premium also appears to have grown in recent decades.

Most economists believe the reason for a growing premium is that the technological change experienced in the post-war period is complementary to high education and high skills in general. Furthermore, the premium has increased despite an enormous increase in the relative supply of highly skilled workers. In essence the growth in supply has not kept up with the growth in demand.

- 6603 reads