One of the reasons Canada signed the North America Free trade Agreement (NAFTA) was that economists convinced the Canadian government that a larger market would enable Canadian producers to be even more efficient than in the presence of trade barriers. This then is a slightly different justification for encouraging trade: rather than opening up trade in order to take advantage of existing comparative advantage, it was proposed that efficiencies would actually increase with market size. So this argument is easily understood if we go back to our description of increasing returns to scale that we developed in Production and cost. Economists told the government that there were several sectors of the economy that were operating on the downward sloping section of their long-run average cost curve.

Increasing returns are evident in the world market place as well as the domestic marketplace. Witness the small number of aircraft manufacturers—Airbus and Boeing are the world’s two major manufacturers of large aircraft. Enormous fixed costs—in the form of research, design, and development—or capital outlays frequently result in decreasing unit costs, and the world marketplace can be supplied at a lower cost if some specialization can take place. What insights does comparative advantage offer here? In fact it is not at all surprising that these corporations, formed several decades ago, emerged in North America and Europe. The development of the end product requires enormous intellectual resources, and in the earlier days of these corporations Europe and North America certainly had a comparative advantage in scientific research.

The theories of absolute and comparative advantage explain why economies specialize in producing some products rather than others. But actual trade patterns are more subtle than this. In North America, we observe that Canadian auto plants produce different models than their counterparts in the U.S. Canada exports some models of a given manufacturer to the United States and imports other models. This is the phenomenon of intra-industry trade and intra-firm trade. How can we explain these patterns?

Intra-industry trade is two-way international

trade in products produced within the same industry.

Intra-industry trade is two-way international

trade in products produced within the same industry.

Intra-firm trade is two-way trade in international

products produced within the same firm.

Intra-firm trade is two-way trade in international

products produced within the same firm.

In the first instance, intra-industry trade reflects the preference of consumers for a choice of brands; consumers do not all want the same car, or the same software, or the same furnishings. The second element to intra-industry trade is that increasing returns to scale characterize many production processes. Let us see if we can transform the returns to scale ideas developed in earlier chapters into a production possibility framework.

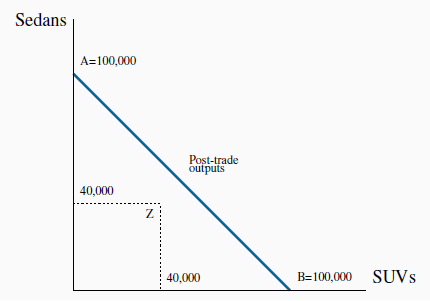

Consider the example presented in Figure 15.3. Hunda Motor Corporation (HMC) currently has a large assembly plant in each of Canada and the US. Restrictions on trade in automobiles between the two countries make it too costly to ship models across the border. Hence Hunda produces both sedans and SUVs in each plant. But for several reasons, switching between models is costly and results in reduced output. Hunda can produce 40,000 vehicles of each type per annum in its plants, but could produce 100,000 of a single model in each plant. This is a situation of increasing returns to scale, and in this instance these scale economies are what determine the trade outcome rather than any innate comparative advantage between the economies.

Hunda can produce either 100,000 of each vehicle or 40,000 of both in each plant. Hence production possibilities are given by the points A, Z, and B. Pre-trade it produces at Z in each economy due to trade barriers. Post-trade it produces at A in one economy and B in the other, and ships the vehicles internationally. Total production increases from 160,000 to 200,000 using the same resources.

- 瀏覽次數:2039