Government policies that improve the purchasing power of low-income households come in two main forms: pure income transfers and price subsidies. Social Assistance payments (“welfare”) or Employment Insurance benefits, for example, provide an increase in income to the needy. Subsidies, on the other hand, enable individuals to purchase particular goods or services at a lower price—for example, rent or daycare subsidies.

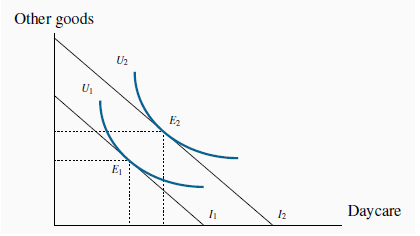

In contrast to taxes, which reduce the purchasing power of the consumer, subsidies and income transfers increase purchasing power. The impact of an income transfer, compared with a pure price subsidy, can be analyzed using Figure 6.12 and Figure 6.13.

An increase in income due to a government transfer shifts the budget constraint from  to

to  .

This parallel shift increases the quantity consumed of the target good (daycare) and other goods, unless one is inferior.

.

This parallel shift increases the quantity consumed of the target good (daycare) and other goods, unless one is inferior.

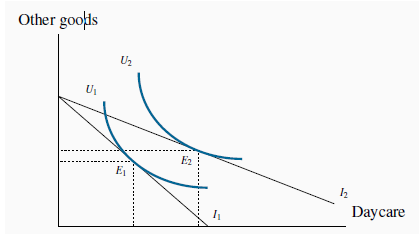

A subsidy to the targeted good, by reducing its price, rotates the budget constraint from  to

to  .

This induces the consumer to direct expenditure more towards daycare and less towards other goods than an income transfer that does not change the relative prices.

.

This induces the consumer to direct expenditure more towards daycare and less towards other goods than an income transfer that does not change the relative prices.

In Figure 6.12, an income transfer increases

income from  to

to  . The new equilibrium at

. The new equilibrium at  reflects an increase in utility, and an increase in the consumption of both daycare and other goods. Suppose now that a

government program administrator decides that, while helping this individual to purchase more daycare accords with the intent of the transfer, she does not intend that government money should

be used to purchase other goods. She therefore decides that a daycare subsidy program might better meet this objective than a pure income transfer.

reflects an increase in utility, and an increase in the consumption of both daycare and other goods. Suppose now that a

government program administrator decides that, while helping this individual to purchase more daycare accords with the intent of the transfer, she does not intend that government money should

be used to purchase other goods. She therefore decides that a daycare subsidy program might better meet this objective than a pure income transfer.

A daycare subsidy reduces the price of daycare and therefore rotates the budget constraint out-wards around the intercept on the vertical axis. At the equilibrium in Figure 6.13, purchases of other goods change very little, and therefore most of the additional purchasing power is allocated to daycare.

The different program outcomes can be understood in terms of income and substitution effects. The pure income transfer policy described in Figure 6.12 contains only income effects, whereas the policy in Figure 6.13 has a substitution effect in addition. Since the relative prices have been altered, the subsidy policy necessarily induces a substitution towards the good whose price has fallen. In this example, where there is a minimal change in “other good” consumption following the daycare subsidy, the substitution effect towards more daycare almost offsets the income effect that increases these other purchases.

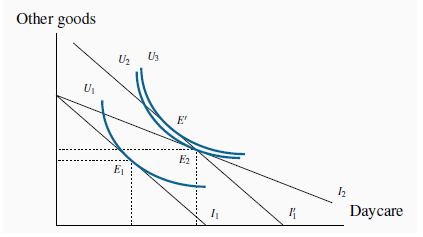

Let us take the example one stage further. From the initial equilibrium  in Figure 6.13, suppose that, instead of a subsidy that took the individual to

in Figure 6.13, suppose that, instead of a subsidy that took the individual to  , we gave an income transfer that enabled the consumer to purchase the combination

, we gave an income transfer that enabled the consumer to purchase the combination  . Such a transfer is represented in Figure 6.14 by a parallel outward shift of the budget constraint from

. Such a transfer is represented in Figure 6.14 by a parallel outward shift of the budget constraint from

to

to  , going through the point

, going through the point  . This budget constraint is very close to the one we used in establishing the substitution effect earlier. We now have a subsidy

policy and an alternative income transfer policy, each permitting the same consumption bundle (

. This budget constraint is very close to the one we used in establishing the substitution effect earlier. We now have a subsidy

policy and an alternative income transfer policy, each permitting the same consumption bundle ( ). The interesting aspect of this pair of possibilities is that the income transfer will enable the consumer to attain a higher

level of satisfaction—for example, at point E'—and will also induce her to consume more of the good on the vertical axis.

). The interesting aspect of this pair of possibilities is that the income transfer will enable the consumer to attain a higher

level of satisfaction—for example, at point E'—and will also induce her to consume more of the good on the vertical axis.

A price subsidy to the targeted good induces the individual to move from  to

to  , facing a budget constraint

, facing a budget constraint  . An income transfer that permits him to consume

. An income transfer that permits him to consume  is given by

is given by  ; but it also permits him to attain a higher level of satisfaction, denoted by E' on the indifference curve

; but it also permits him to attain a higher level of satisfaction, denoted by E' on the indifference curve  .

.

Application Box: Daycare subsidies in Quebec

The Quebec provincial government subsidizes daycare very heavily. In the network of daycares that are part of the government-sponsored “Centres de la petite enfance”, parents can place their children in daycare for less than $10 per day. This policy of providing daycare at a fraction of the actual cost was originally intended to enable parents on lower incomes to work in the marketplace, without having to spend too large a share of their earnings on daycare. However, the system was not limited to those households on low income. This policy is exactly the one described in Figure 6.14.

The consequences of such subsidization were predictable: extreme excess demand, to such an extent that children are frequently placed on waiting lists for daycare places not long after they are born. Annual subsidy costs amount to almost $2 billion per year. Universality means that many low-income parents are not able to obtain subsidized daycare places for their children, because middle- and higher-income families get many of the limited number of such spaces. The Quebec government, like many others, also subsidizes the cost of daycare for families using the private daycare sector, through income tax credits.

- 5442 reads