The consumer and producer surplus concepts we have developed are extremely powerful tools of analysis, but the world is not always quite as straightforward as simple models indicate. For example, many suppliers generate pollutants that adversely affect the health of the population, or damage the environment, or both. The term externality is used to denote such impacts. Externalities impact individuals who are not participants in the market in question, and the effects of the externalities may not be captured in the market price. For example, electricity-generating plants that use coal reduce air quality, which, in turn, adversely impacts individuals who suffer from asthma or other lung ailments. While this is an example of a negative externality, externalities can also be positive.

An externality is a benefit or cost falling on

people other than those involved in the activity’s market. It can create a difference between private costs or values and social costs or values.

An externality is a benefit or cost falling on

people other than those involved in the activity’s market. It can create a difference between private costs or values and social costs or values.

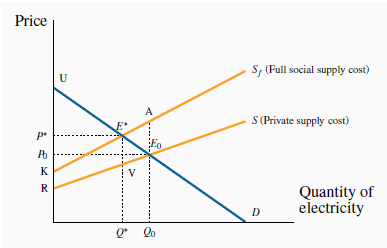

We will now show why markets characterized by externalities are not efficient, and also show how these externalities might be corrected or reduced. The essence of an externality is that it creates a divergence between private costs/benefits and social costs/benefits. If a steel producer pollutes the air, and the steel buyer pays only the costs incurred by the producer, then the buyer is not paying the full “social” cost of the product. The problem is illustrated in Figure 5.5.

A negative externality is associated with this good. S measures private costs, whereas  measures the full social cost. The socially optimal output is Q*, not the market outcome

measures the full social cost. The socially optimal output is Q*, not the market outcome  . Beyond Q* the real cost exceeds the demand value; therefore Qo is not an efficient

output. A ax that increases P to P* and reduces output is one solution to the externality.

. Beyond Q* the real cost exceeds the demand value; therefore Qo is not an efficient

output. A ax that increases P to P* and reduces output is one solution to the externality.

- 瀏覽次數:2794