Public goods are sometimes called collective consumption goods, on account of their non-rivalrous and non-excludability characteristics. For example, if the government meteorological office provides daily forecasts over the nation’s airwaves, it is no more expensive to supply that information to one million than to one hundred individuals in the same region. Its provision to one is not rivalrous with its provision to others – in contrast to private goods that cannot be ‘consumed’ simultaneously by more than one individual. In addition, it may be difficult to exclude certain individuals from receiving the information.

Public goods are

non-rivalrous, in that they can be consumed simultaneously by more than one individual; additionally they may have a non-excludability characteristic.

Public goods are

non-rivalrous, in that they can be consumed simultaneously by more than one individual; additionally they may have a non-excludability characteristic.

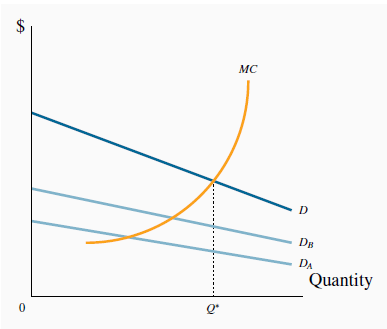

Examples of such goods and services abound: highways (up to their congestion point), street lighting, information on trans-fats and tobacco, or public defence provision. Such goods pose a problem for private markets: if it is difficult to exclude individuals from their consumption, then potential private suppliers will likely be deterred from supplying them because the suppliers cannot generate revenue from free-riders. Governments therefore normally supply such goods and services. But how much should governments supply? An answer is provided with the help of Figure 14.1.

The total demand for the public good D is the vertical sum of the individual demands  and

and  .

The optimal provision is where theMC equals the aggregate marginal valuation, as defined by the demand curve D. At the optimum Q*, each individual is supplied the same amount of the public

good.

.

The optimal provision is where theMC equals the aggregate marginal valuation, as defined by the demand curve D. At the optimum Q*, each individual is supplied the same amount of the public

good.

This is a supply-demand diagram with a difference. The supply side is conventional, with the MC of production representing the supply curve. An efficient use of the economy’s resources, we already know, dictates that an amount should be produced so that the cost at the margin equals the benefit to consumers at the margin. In contrast to the total market demand for private goods, which is obtained by summing individual demands horizontally, the demand for public goods is obtained by summing individual demands vertically.

Figure 14.1 depicts an economy

with just two individuals whose demands for street lighting are given by  and

and  .

These demands reveal the value each individual places on the various output levels of the public good, measured on the x-axis. However, since each individual can consume the public good

simultaneously, the aggregate value of any output produced is the sum of each individual valuation. The valuation in the market of any quantity produced is therefore the vertical sum of the

individual demands. D is the vertical sum of

.

These demands reveal the value each individual places on the various output levels of the public good, measured on the x-axis. However, since each individual can consume the public good

simultaneously, the aggregate value of any output produced is the sum of each individual valuation. The valuation in the market of any quantity produced is therefore the vertical sum of the

individual demands. D is the vertical sum of  and

and  , and the optimal output is Q*. At this equilibrium each individual consumes the

same quantity of street lighting, and the MC of the last unit supplied equals the value placed upon it by society – both individuals. Note that this ‘optimal’ supply depends upon the income

distribution, as we have stated several times to date. A different distribution of income may give rise to different demands

, and the optimal output is Q*. At this equilibrium each individual consumes the

same quantity of street lighting, and the MC of the last unit supplied equals the value placed upon it by society – both individuals. Note that this ‘optimal’ supply depends upon the income

distribution, as we have stated several times to date. A different distribution of income may give rise to different demands  and

and  ,

and therefore a different ‘optimal’ output.

,

and therefore a different ‘optimal’ output.

Efficient supply of public

goods is where the marginal cost equals the sum of individual marginal valuations, and each individual consumes the same quantity.

Efficient supply of public

goods is where the marginal cost equals the sum of individual marginal valuations, and each individual consumes the same quantity.

A challenge in providing the optimal amount of government-supplied public goods is to know the value that users may place upon them – how can the demand curves  and

and  , be ascertained, for example, in Figure 14.1? In contrast to markets for private goods, where consumer demands are

essentially revealed through the process of purchase, the demands for public goods may have to be uncovered by means of surveys that are designed so as to elicit the true valuations that users

place upon different amounts of a public good. A second challenge relates to the pricing and funding of public goods: for example, should highway lighting be funded from general tax revenue, or

should drivers pay for it? These are complexities that are beyond our scope of our current inquiry.

, be ascertained, for example, in Figure 14.1? In contrast to markets for private goods, where consumer demands are

essentially revealed through the process of purchase, the demands for public goods may have to be uncovered by means of surveys that are designed so as to elicit the true valuations that users

place upon different amounts of a public good. A second challenge relates to the pricing and funding of public goods: for example, should highway lighting be funded from general tax revenue, or

should drivers pay for it? These are complexities that are beyond our scope of our current inquiry.

Application Box: Are Wikipedia and Google public goods?

Wikipedia is one of the largest on-line sources of free information in the world. It is an encyclopedia that functions in multiple languages and that furnishes information on millions of topics. It is freely accessible, and is maintained and expanded by its users. Google is the most frequently used search engine on the World Wide Web. It provides information to millions of users simultaneously on every subject imaginable, free of charge. Are these services public goods in the sense we have described?

Very few goods and services are pure public goods. In that context both Google and Wikipedia are public goods. Wikipedia is funded by philanthropic contributions, and its users expand its range by posting information on its servers. Google is funded from advertising revenue. Technically, a pure public good is available to additional users at zero marginal cost. This condition is essentially met by these services since their server capacity rarely reaches its limit. Nonetheless, they are constantly adding server capacity, and in that sense cannot furnish their services to an unlimited number of additional users at no additional cost.

Knowledge is perhaps the ultimate public good; Wikipedia and Google both disseminate knowledge, knowledge which has been developed through the millennia by philosophers, scientists, artists, teachers, research laboratories and universities.

- 3202 reads