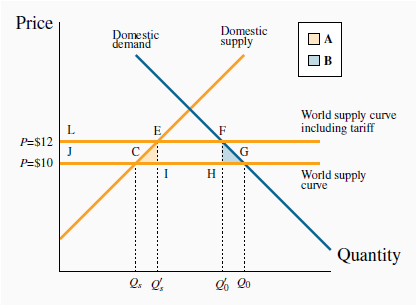

Figure 15.4 describes how tariffs operate. We can think of this as the wine market—a market that is heavily taxed in Canada. The world price of Cabernet Sauvignon is $10 per bottle, and this is shown by the horizontal supply curve at that price. It is horizontal because we assume that the world can supply us with any amount we wish to buy at the same price. The Canadian demand for this wine is given by the demand curve D, and Canadian suppliers have a supply curve given by S (Canadian Cabernet is assumed to be of the same quality as the imported variety in this example). At a price of $10, Canadian consumers wish to buy QD litres, and domestic producers wish to supply QS litres. The gap between domestic supply QS and domestic demand QD is filled by imports. This is the free trade equilibrium.

At a world price of $10 the domestic quantity demanded is Qo. Of this amount Qs is supplied by domestic producers and the remainder by foreign producers. A tariff increases the world price to $12. This reduces demand to Q'o; the domestic component of supply increases to Q's. Of the total loss in consumer surplus (LFGJ), tariff revenue equals EFHI, increased surplus for domestic suppliers equals LECJ, and the deadweight loss is therefore the sum of the triangular areas A and B.

If the government now imposes a 20 percent tariff on imported wines, foreign wine sells for $12 a bottle, inclusive of the tariff. The tariff raises the domestic ‘tariff-inclusive’ price above

the world price, and this shifts the supply of this wine upwards. By raising wine prices in the domestic market, the tariff protects domestic producers by raising the domestic price at which

imports become competitive. Those domestic suppliers who were previously not quite competitive at a global price of $10 are now competitive. The total quantity demanded falls

from  to

to  at the new equilibrium F. Domestic producers supply the amount Q's and imports fall to

the amount (

at the new equilibrium F. Domestic producers supply the amount Q's and imports fall to

the amount ( -

-  ). Reduced imports are partly displaced by domestic producers who can supply at prices

between $10 and $12. Hence, imports fall both because total consumption falls and because domestic suppliers can displace some imports under the protective tariff.

). Reduced imports are partly displaced by domestic producers who can supply at prices

between $10 and $12. Hence, imports fall both because total consumption falls and because domestic suppliers can displace some imports under the protective tariff.

Since the tariff is a type of tax, its impact in the market depends upon the elasticities of supply and demand, as illustrated in Measures of response: elasticities and Welfare economics and externalities: the more elastic is the demand curve, the more a given tariff reduces imports. In contrast, if it is inelastic the quantity of imports declines less.

Application Box: Tariffs – the national policy of J.A. MacDonald

In Canada, tariffs were the main source of government revenues, both before and after Confederation in 1867 and up to World War I. They provided “incidental protection” for domestic

manufacturing. After the 1878 federal election, tariffs were an important part of the National Policy introduced by the government of Sir John A. MacDonald. The broad objective was to create

a Canadian nation based on east-west trade and growth.

This National Policy had several dimensions. Initially, to support domestic manufacturing, it increased tariff protection on foreign manufactured goods, but lowered tariffs on raw materials

and intermediate goods used in local manufacturing activity. The profitability of domestic manufacturing improved. But on a broader scale, tariff protection, railway promotion, Western

settlement, harbour development, and transport subsidies to support the export of Canadian products were intended to support national economic development. Although “reciprocity agreements”

with the United States removed duties on commodities for a time, tariff protection for manufactures was maintained until the GATT negotiations of the post-World War II era.

- 5782 reads