We have now described the market and firm-level equilibrium in the short run. However, this equilibrium may be only temporary; whether it can be sustained or not depends upon whether profits (or losses) are being incurred, or whether all participant firms are making what are termed normal profits. Such profits are considered an essential part of a firm’s operation. They reflect the opportunity cost of the resources used in production. Firms do not operate if they cannot make a minimal, or normal, profit level. Above such profits are economic profits (also called supernormal profits), and these are what entice entry into the industry.

Economists and accountants measure profits differently. Accounting profits are the difference between revenues and costs incurred. But an economist is interested additionally in the opportunity cost of the resources used in production. To illustrate: suppose the owner of BDS is paying himself a salary of thirty thousand dollars a year. This is an explicit cost that enters the firm’s books, and is the cost that an accountant will use to reflect the cost of management services to the firm. But if the owner could earn seventy thousand dollars a year as a ski and snowboard resort manager, then by staying in his manufacturing business he is giving up the opportunity to earn his real value in the marketplace. Obviously he would be unwise to continue in the low paying job indefinitely, even though he may be willing to take a lower salary in order to get his firm established.

The critical point in this distinction between accounting and economic cost is that the decision to enter or leave a market in the longer term is based on what the inputs in the firm can earn in the market place. That is, economic profits rather than accounting profits will determine the equilibrium number of firms in the long term.

Normal profits are required to induce suppliers to

supply their goods and services. They reflect opportunity costs and can therefore be considered as a type of cost component.

Normal profits are required to induce suppliers to

supply their goods and services. They reflect opportunity costs and can therefore be considered as a type of cost component.

Economic (supernormal) profits are those profits

above normal profits that induce firms to enter an industry. Economic profits are based on the opportunity cost of the resources used in production.

Economic (supernormal) profits are those profits

above normal profits that induce firms to enter an industry. Economic profits are based on the opportunity cost of the resources used in production.

Accounting profits are the difference between

revenues and actual costs incurred.

Accounting profits are the difference between

revenues and actual costs incurred.

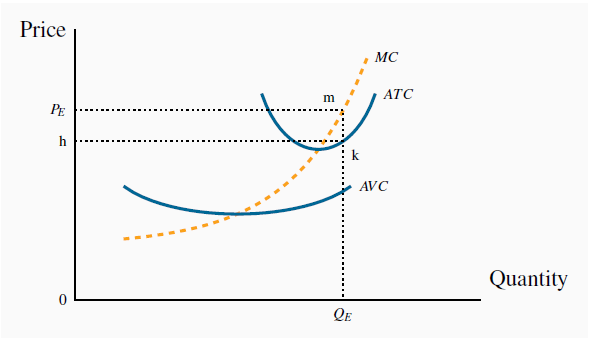

Let us begin by supposing that the market equilibrium described in Figure 9.4 results in profits being made by some firms. Such an outcome is described in Figure 9.5, where the price is more than sufficient to cover ATC. At the price

, a profit-making firm supplies the quantity

, a profit-making firm supplies the quantity  , as determined by its MC curve. On average, the cost of producing each unit of output,

, as determined by its MC curve. On average, the cost of producing each unit of output,

, is defined by the point on the ATC at that output level, point k.

Profit per unit is thus given by the value mk – the difference between revenue per unit and cost per unit. Total (economic) profit is therefore the area

, is defined by the point on the ATC at that output level, point k.

Profit per unit is thus given by the value mk – the difference between revenue per unit and cost per unit. Total (economic) profit is therefore the area  mkh, which is quantity times profit per unit.

mkh, which is quantity times profit per unit.

At the price  , determined by the intersection of market demand

and market supply, an individual firm produces the amount

, determined by the intersection of market demand

and market supply, an individual firm produces the amount  . The ATC

of this output is k and therefore profit per unit is mk. Total profit is therefore

. The ATC

of this output is k and therefore profit per unit is mk. Total profit is therefore  mkh=0

mkh=0 mk=TR-TC.

mk=TR-TC.

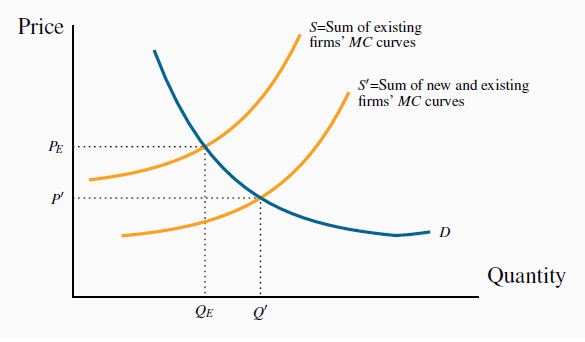

While  represents an equilibrium for the firm, it is only a

short-run or temporary equilibrium for the industry. The assumption of free entry and exit implies that the presence of economic profits will induce new entrepreneurs to set up shop and start

producing. The impact of this dynamic is illustrated in Figure 9.6. An increased number of firms shifts supply rightwards to become S', thereby increasing the amount supplied at any price. The impact on price

of this supply shift is evident: With an unchanged demand, the equilibrium price must fall.

represents an equilibrium for the firm, it is only a

short-run or temporary equilibrium for the industry. The assumption of free entry and exit implies that the presence of economic profits will induce new entrepreneurs to set up shop and start

producing. The impact of this dynamic is illustrated in Figure 9.6. An increased number of firms shifts supply rightwards to become S', thereby increasing the amount supplied at any price. The impact on price

of this supply shift is evident: With an unchanged demand, the equilibrium price must fall.

If economic profits result from the price  new firms enter the

industry. This entry increases the market supply to S' and the equilibrium price falls to P' . Entry continues as long as economic profits are present. Eventually the price is driven to a level

where only normal profits are made, and entry ceases.

new firms enter the

industry. This entry increases the market supply to S' and the equilibrium price falls to P' . Entry continues as long as economic profits are present. Eventually the price is driven to a level

where only normal profits are made, and entry ceases.

How far will the price fall, and how many new firms will enter this profitable industry? As long as economic profits exist new firms will enter and the resulting increase in supply will continue to drive the price downwards. But, once the price has been driven down to the minimum of the ATC of a representative firm, there is no longer an incentive for new entrepreneurs to enter. Therefore, the long-run industry equilibrium is where the market price equals the minimum point of a firm’s ATC curve. This generates normal profits, and there is no incentive for firms to enter or exit.

A long-run equilibrium in a competitive industry

requires a price equal to the minimum point of a firm’s ATC. At this point, only normal profits exist, and there is no incentive for firms to enter or exit.

A long-run equilibrium in a competitive industry

requires a price equal to the minimum point of a firm’s ATC. At this point, only normal profits exist, and there is no incentive for firms to enter or exit.

In developing this dynamic, we began with a situation in which economic profits were present. However, we could have equally started from a position of losses. With a market price between the minimum of the AVC and the minimum of the ATC in Figure 9.5, revenues per unit would exceed costs per unit. When firms cannot cover their ATC in the long run, they will cease production. Such closures must reduce aggregate supply; consequently the market supply curve contracts, rather than expands as it did in Figure 9.6. The reduced supply drives up the price of the good. This process continues as long as firms are making losses. Final industry equilibrium is attained only when price reaches a level where firms can make a normal profit. Again, this will be at the minimum of the typical firm’s ATC.

Accordingly, the long-run equilibrium is the same, regardless of whether we begin from a position in which firms are incurring losses, or where they are making profits.

- 瀏覽次數:2345