Positive economics studies objective or scientific explanations of how the economy functions. Its aim is to understand and generate predictions about how the economy may respond to changes and policy initiatives. In this effort economists strive to act as detached scientists, regardless of political sympathies or ethical code. Personal judgments and preferences are (ideally) kept apart. In this particular sense, economics is similar to the natural sciences such as physics or biology.

In contrast, normative economics offers recommendations based partly on value judgments. While economists of different political persuasions can agree that raising the income tax rate would lead to a general reduction in the number of hours worked, they may yet differ in their views on the advisability of such a rise. One may believe that the additional revenue that may come in to government coffers is not worth the disincentives to work; another may think that, if such monies can be redistributed to benefit the needy or provide valuable infrastructure, the negative impact on the workers paying the income tax is worth it.

Positive economics studies objective or scientific

explanations of how the economy functions.

Positive economics studies objective or scientific

explanations of how the economy functions.

Normative economics offers recommendations that

incorporate value judgments.

Normative economics offers recommendations that

incorporate value judgments.

Scientific research can frequently resolve differences that arise in positive economics—not so in normative economics. For example, if we claim that “the elderly have high medical bills, and the government should cover all of the bills”, we are making both a positive and a normative statement. The first part is positive, and its truth is easily established. The latter part is normative, and individuals of different beliefs may reasonably differ. Some people may believe that the money would be better spent on the environment and have the aged cover at least part of their own medical costs. Economics cannot be used to show that one of these views is correct and the other false. They are based on value judgments, and are motivated by a concern for equity. Equity is a vital guiding principle in the formation of policy and is frequently, though not always, seen as being in competition with the drive for economic growth. Equity is driven primarily by normative considerations. Few economists would disagree with the assertion that a government should implement policies that improve the lot of the poor and dispossessed—but to what degree?

Economic equity is concerned with the distribution

of well-being among members of the economy.

Economic equity is concerned with the distribution

of well-being among members of the economy.

Most economists hold normative views, sometimes very strongly. They frequently see their role as not just to analyze economic issues from a positive perspective, but also to champion their normative cause in addition. Conservative economists see a smaller role for government than left-leaning economists. A scrupulous economist will distinguish her positive from her normative analysis.

Many economists see a conflict between equity and the efficiency considerations that we developed in Chapter 1. For example, high taxes may provide disincentives to work in the marketplace and therefore reduce the efficiency of the economy: plumbers and gardeners may decide to do their own gardening and their own plumbing because, by staying out of the marketplace where monetary transactions are taxed, they can avoid the taxes. And avoiding the taxes may turn out to be as valuable as the efficiency gains they forgo.

In other areas the equity efficiency trade-off is not so obvious: if taxes (that may have disincentive effects) are used to educate individuals who otherwise would not develop the skills that follow education, then economic growth may be higher as a result of the intervention.

Application Box: Statistics for policy makers

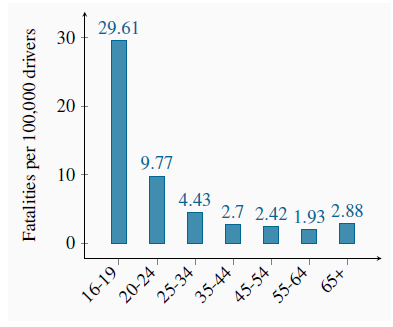

Data are an integral part of policy making in the public domain. A good example of this is in the area of road safety. Road fatalities have fallen dramatically in recent decades in Canada, in large measure due to the introduction of safety measures such as speed limits, blood-alcohol limits, seat belt laws, child-restraint devices and so forth. Safety policies are directed particularly strongly towards youth: they have a lower blood-alcohol limit, a smaller number of permitted demerit points before losing their license, a required period of learning (driver permit) and so forth. While fatalities among youth have fallen in line with fatalities across the age spectrum, they are still higher than for other age groups. Figure 2.7 presents data on fatalities per licensed driver by age group in Canada relative to the youngest age group. Note the strong non-linear pattern to the data – fatalities decline quickly, then level off and again increase for the oldest age group.

In keeping with these data, drivers are now required to pass a driving test in most provinces once they attain a certain age – usually 80, because the data indicate that fatalities increase when drivers age. See:

CANADIAN MOTOR VEHICLE TRAFFIC COLLISION STATISTICS 2009, Transport Canada.

- 3395 reads