Canada is a federal state, in which the federal, provincial and municipal governments exercise different powers and responsibilities. In contrast, most European states are unitary and power is not devolved to their regions to the same degree as in Canada or the US or Australia. Federalism confers several advantages over a unitary form of government where an economy is geographically extensive, or where identifiable differences distinguish one region from another: regions can adopt different policies in response to the expression of different preferences by their respective voters; smaller governments may be better at experimentation and the introduction of new policies than large governments; political representatives are ‘closer’ to their constituents.

Despite these advantages, the existence of an additional level of government creates a tension between these levels. Such tension is evident in every federation, and federal and provincial governments argue over the appropriate division of taxation powers and revenue-raising power in general: for example, how should the royalties and taxes from oil and gas deposits off Newfoundland and Labrador be distributed – to the federal government or the provincial government?

In Canada, the federal government collects more in tax revenue than it expends on its own programs.

This is a feature of most federations. The provinces simultaneously face a shortfall in their own revenues relative to their program expenditure requirements. The federal government therefore redistributes, or transfers, funds to the provinces so that the latter can perform their constitutionally-assigned roles in the economy. The fact that the federal government bridges this fiscal gap gives it a degree of power over the provinces. This influence is commonly termed federal spending power.

Spending power of a

federal government arises when the federal government can influence lower level governments due to its financial rather than constitutional power.

Spending power of a

federal government arises when the federal government can influence lower level governments due to its financial rather than constitutional power.

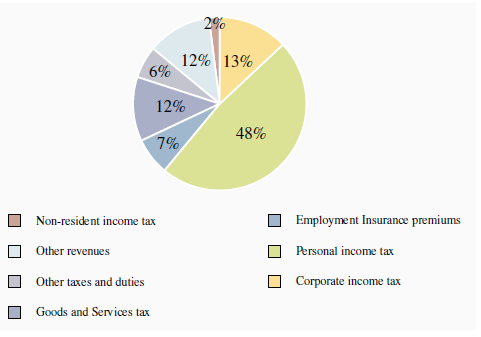

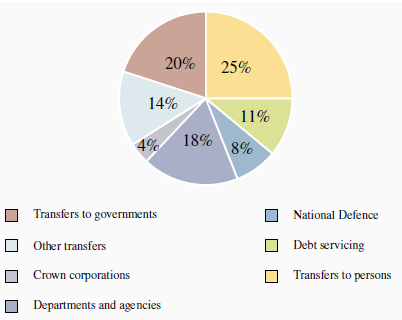

The principal revenue sources for financing government activity are given in the pie chart in Figure 14.2 for the fiscal year 2010/11, and the expenditure of these revenues is broken down in Figure 14.3. Further details are accessible at the Department of Finance’s web site, though students should be aware that government accounts come in many forms. Total revenues for this fiscal year amounted to $237b.

The federal and provincial governments each transfer these revenues to individuals and other levels of government, supply goods and services directly, and also pay interest on accumulated borrowings – the national debt or provincial debt.

Provincial and local governments supply more goods and services than the federal government - health, drug insurance, education and welfare are the responsibility of provincial and municipal governments. In contrast, national defence, the provision of main traffic arteries, Corrections Canada and a variety of transfer programs to individuals – such as Employment Insurance, Old Age Security and the Canada Pension Plan - are federally funded. The greater part of federal revenues goes towards transfers to individuals and provincial governments, as opposed to the supply of goods and services.

- 2689 reads