In the opening chapter of this text we emphasized the importance of opportunity cost and differing efficiencies in the production process as a means of generating benefits to individuals through trade in the marketplace. The simple example we developed illustrated that, where individuals differ in their efficiency levels, benefits can accrue to each individual as a result of specializing and trading. In that example it was assumed that individual A had an absolute advantage in producing one product and that individual Z had an absolute advantage in producing the second good. This set-up could equally well be applied to two economies that have different efficiencies and are considering trade, with the objective of increasing their consumption possibilities. Technically, we could replace Amanda and Zoe with Argentina and Zambia, and nothing in our analysis would have to change in order to illustrate that consumption gains could be attained by both Argentina and Zambia as a result of specialization and trade.

Remember: The opportunity cost of a good is the quantity of another good or service given up in order to have one more unit of the good in question.

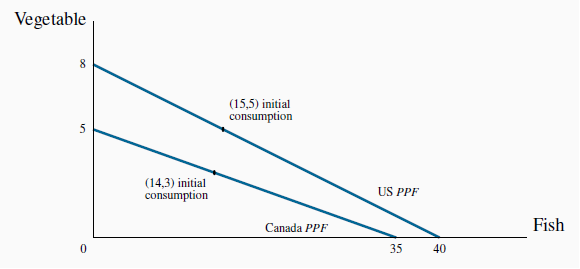

So, consider two economies with differing production capabilities, as illustrated in Figure 15.1 and Figure 15.2. In this instance we will assume that one economy has an absolute advantage in both goods, but the degree of that advantage is greater in one good than the other. In international trade language, there exists a comparative advantage as well as an absolute advantage. It is frequently a surprise to students that this situation has the capacity to yield consumption advantages to both economies if they engage in trade, even though one is absolutely more efficient in producing both of the goods. This is what is called the principle of comparative advantage, and it states that even if one country has an absolute advantage in producing both goods, gains to specialization and trade still materialize, provided the opportunity cost of producing the goods differs between economies. This is a remarkable result, and much less intuitive than the principle of absolute advantage. We explore it with the help of the example developed in Figure 15.1 and Figure 15.2.

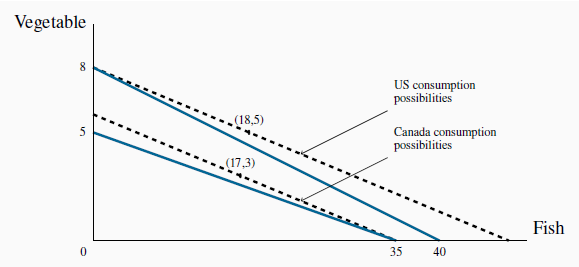

Canada specializes completely in Fish at (35,0), where it has a comparative advantage. Similarly, the US specializes in Vegetable at (0,8). They trade at a rate of 1:6. The US trades 3V to Canada in return for 18F.

Post specialization the economies trade 1V for 6F. Total production is 35F plus 8V. Hence once consumption possibility would be (18,5) for the US and (17,3) for Canada. Here Canada exchanges 18F in return for 3V.

Principle of comparative advantage states that

even if one country has an absolute advantage in producing both goods, gains to specialization and trade still materialize, provided the opportunity cost of producing the goods differs between

economies.

Principle of comparative advantage states that

even if one country has an absolute advantage in producing both goods, gains to specialization and trade still materialize, provided the opportunity cost of producing the goods differs between

economies.

The two economies considered are the US and Canada. Their production possibilities are defined by the PPFs in Figure 15.1. Canada can produce 5 units of V or 35 units of F, or any combination defined by the line joining these points. The US can produce 8V or 40F, or any combination defined by its PPF 1 . Let Canada initially consume 3V and 14F, and the US consume 5V and 15F. These combinations lie on their respective PPFs. We use the term autarky to denote the no-trade situation.

The opportunity cost of a unit of V in Canada is 7F (the slope of Canada’s PPF is 5/35 = 1/7). In the US the opportunity cost of one unit of V is 5F (slope is 8/40 = 1/5). In this set-up the US is more efficient in producing V than F relative to Canada, as reflected by the opportunity costs. Hence we say that the US has a comparative advantage in the production of V and that Canada has therefore a comparative advantage in producing F.

Prior to trade each economy is producing all of the goods it consumes. This no-trade state is termed autarky.

Autarky denotes the no-trade situation.

Autarky denotes the no-trade situation.

- 3552 reads