We can make this idea more precise, using the pizza economy to illustrate. Imagine that our economy is composed of two sectors, which we call households and firms. Households supply labor to firms and are paid wages in return. Firms use that labor to produce pizzas and sell those pizzas to households. There is a flow of goods (pizzas) from firms to households and a flow of labor services (worker hours) from households to firms. Because there are two sides to every transaction, there is also a flow of dollars from households to firms, as households purchase pizza, and a flow of dollars from firms to households, as firms pay workers.

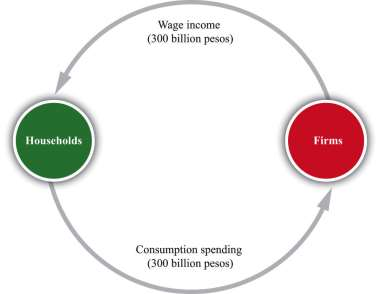

For now, think of firms as very simple entities that pay out all the income they receive in the form of wages to workers. As a result, 300 billion pesos flow from the household sector to the firm sector (the purchase of pizzas) each year, while 300 billion pesos flow from the firm sector to the household sector (the payment of wages). These flows of pesos are illustrated in Figure 3.11 The Simplest Version of the Circular Flow . Think of this diagram as representing the interaction of many households with many firms. A particular household works for one (or perhaps a few firms) but purchases goods and services from many firms. (If you like, imagine that different firms specialize in different kinds of pizza.) A feature of modern economies is that individuals specialize in production of goods and services but generalize in consumption by consuming many varieties of goods and services.

The circular flow of income follows the money in an economy. In the pizza economy, firms produce pizzas and sell them to households, while households sell labor to firms and purchase pizzas from them.

The circular flow reveals that there are several different ways to measure the level of economic activity. From the household perspective, we can look at either the amount of income earned by households or their level of spending. From the firm perspective, we can look at either the level of revenues earned from sales or the amount of their payments to workers and shareholders. In all cases, the level of nominal economic activity would be measured at 300 billion pesos.

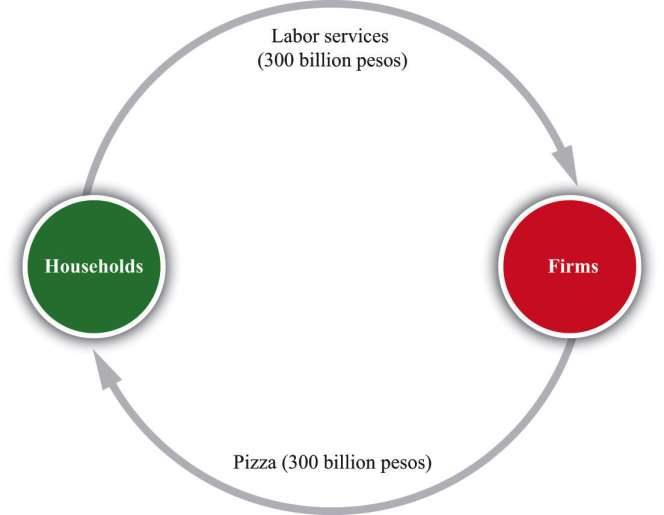

Corresponding to the flows of pesos shown in Figure 3.11 The Simplest Version of the Circular Flow , there are flows of goods and services between these sectors, as shown in Figure 3.12 The Flows of Goods and Labor within the Circular Flow . The wage income received by consumers is payment for labor services that flow from households to firms. The consumption spending of households is payment for the goods that flow from firms to households.

There are flows of goods and labor services that correspond to the flows of pesos shown in Figure 3.11 The Simplest Version of the Circular Flow . Three hundred billion pesos worth of pizza flows from firms to households, and 300 billion pesos worth of labor services flow from households to firms.

Of course, there are also flows of dollars within the household and firm sectors as well as between them. Importantly, firms purchase lots of goods and services from other firms. One of the beauties of the circular flow construct is that it allows us to describe overall economic activity without having to go into the detail of all the flows among firms.

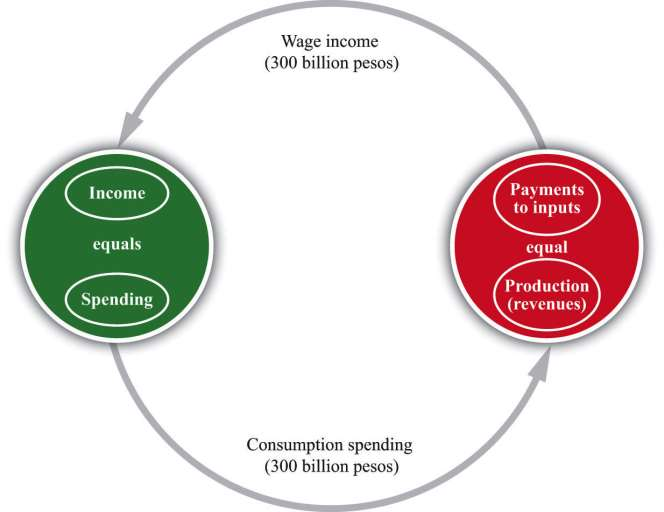

Figure 3.13 Income, Spending, Payments to Inputs, and Revenues in the Simple Circular Flow shows us that the flows in and out of each sector must balance. In the household sector, total spending by the household equals total income for the household. If spending equals income for each individual household, then spending also equals income for the household sector as a whole. Similarly, each firm has a balance sheet. Accounting rules ensure that all of a firm’s revenues must ultimately show up on the other side of the balance sheet as payments for the inputs that the firm uses (in our simple example, the firm’s only input is labor). As this is true for each individual firm, it is also true for the sector as a whole.

In each household, and thus in the household sector as a whole, income must equal spending. In each firm, and thus in the firm sector as a whole, revenues must equal payments to inputs. GDP measures the production of the economy and total income in the economy. We can use the terms production, income, spending, and GDP interchangeably.

Although this version of the circular flow is simple, it teaches us four key insights that remain true (albeit in slightly refined forms) in more sophisticated versions as well.

- Spending = production. The total value of all spending by households becomes an inflow into the firm sector and thus ends up on the revenue side of a firm’s balance sheet.The revenues received by firms provide us with a measure of the total value of production in an economy.

- Production = payments to inputs. Flows in and out of the firm sector must balance. The revenues received by firms are ultimately paid out to households.

- Payments to inputs = income. Firms are legal entities, not people. We may talk in common speech of a firm “making money,” but any income generated by a firm must ultimately end up in the hands of real people—that is, in the household sector of an economy. The total value of the goods produced by firms becomes an outflow of dollars from the firm sector. These dollars end up in the hands of households in the form of income. (This ownership is achieved through many forms, ranging from firms that are owned and operated by individuals to giant corporations whose ownership is determined by stock holdings. Not all households own firms in this way, but in macroeconomics it is sufficient to think about the average household that does own stock in firms.)

- Income = spending. We complete the circle by looking at the household sector. The dollars that flow into the household sector are the income of that sector. They must equal the dollars that flow out of the household sector—its spending.

The circular flow of income highlights a critical fact of national income accounting:

GDP = income = spending = production.

Earlier, we emphasized that GDP measures the production of an economy. Now we see that GDP is equally a measure of the income of an economy. Again, this reflects the fact that there are two sides to each transaction. We can use the terms income, spending,production, and GDP completely interchangeably.

What does this mean for your assessment of Argentina? For one thing, it tells you that the decline in real GDP implies a corresponding decline in income. Economists pay a great deal of attention to real GDP statistics for exactly this reason: such statistics provide information on the total amount of income earned in an economy.

- 4345 reads