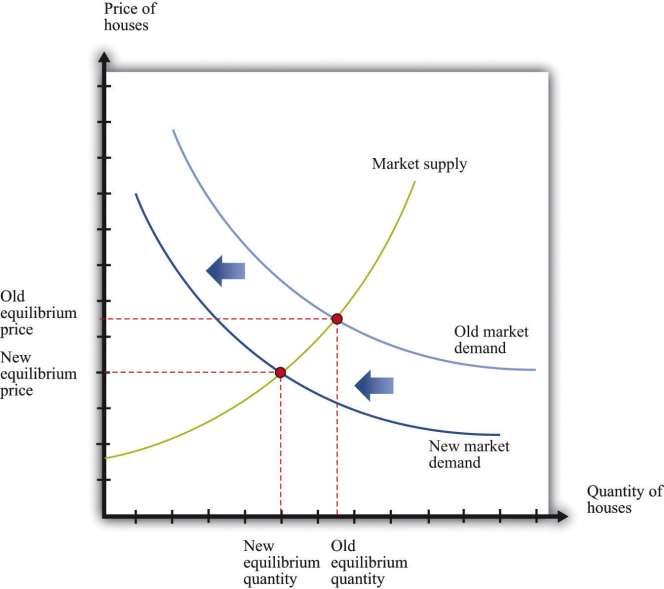

Consider, as before, the market for new houses and suppose there is a reduction in spending on houses. Market demand shifts inward, causing a decrease in the price of houses, as shown in ***Figure 7.6 "An Inward Shift in Market Demand for Houses". The lower price means that construction firms choose to build fewer houses; there is a movement along the supply curve.

As before, the effects are not confined to the housing market. Construction firms demand less labor, so the wages of these workers decrease. Employment in the construction industry declines, but these workers now seek jobs in other sectors of the economy. The increased supply of labor in these sectors reduces wages and thus makes it more attractive for firms to increase their hiring. Supply curves in other sectors shift rightward. Moreover, the income that was being spent on housing will instead be spent somewhere else in the economy, so we expect to see rightward shifts in demand curves in other sectors as well. In summary, if we are looking at the whole economy, a decrease in spending in one market is not that different from a decrease in technology in one market: we expect a reduction in one sector to lead to expansions in other sectors. The economy still appears to be self-stabilizing.

In this story, as is usual when we use supply and demand, we presumed that prices and wages adjust quickly to bring supply and demand into line. This is critical for the effective functioning of markets: for markets to do a good job of matching up demand and supply, wages and prices must respond rapidly to differences between supply and demand.Flexible prices adjust immediately to shifts in supply and demand curves so that price is always at the point where supply equals demand. If, for example, the quantity of labor supplied exceeds the quantity of labor demanded, flexible wages decrease quickly to bring the labor market back into equilibrium.

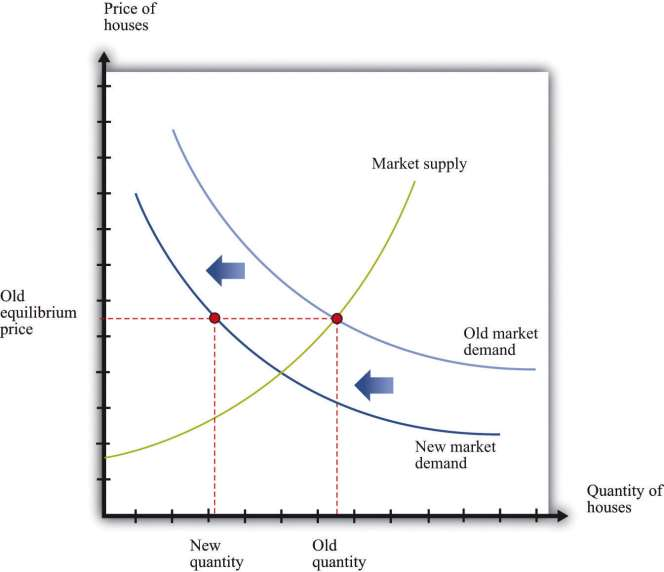

Suppose we instead entertain the possibility that wages and prices do not immediately adjust. Sticky prices do not react immediately to shifts in supply and demand curves, and the adjustment to equilibrium can take some time. We defer for the moment the discussion of why prices might be sticky and concentrate instead on the implications of this new idea about how markets work. The easiest way to see the effects of price stickiness is to suppose that prices do not change at all. ***Figure 7.7 "A Shift in Demand for Houses When Prices Are Sticky" shows the impact of a decrease in demand for houses when the price of houses is completely sticky. If you compare ***Figure 7.7 "A Shift in Demand for Houses When Prices Are Sticky" to ***Figure 7.6 "An Inward Shift in Market Demand for Houses", you see that a given shift in demand leads to a larger change in the quantity produced.

What about the effects on other markets? As before, a decrease in demand for housing will cause construction workers to lose their jobs. If wages are sticky, these workers may become unemployed for a significant period of time. Their income decreases, and they consume fewer goods and services. So, for example, the demand for beef in the economy might decrease because unemployed construction workers buy cheaper meat. This means that the demand for beef shifts inward. The reduction in activity in the construction sector leads to a reduction in activity in the beef sector. And the process does not stop there—the reduced income of cattle farmers and slaughterhouse workers will, in turn, spill over to other sectors.

What has happened to the self-stabilizing economy described earlier? First, sticky wages and prices impede the incentives for workers to flow from one sector to another. If wages are sticky, then the reduction in labor demand in the construction sector does not translate into lower wages. Thus there is no incentive for other sectors to expand. Instead, these other sectors, such as food, see a decrease in demand for their product, which leads them to contract as well. Second, the decrease in income means that it is possible to see decreases in demand across the entire economy. It no longer need be the case that reductions in spending in one area lead to increased spending in other sectors.

- 1617 reads