Unemployment suggests a mismatch between supply and demand. People who are unemployed want to have a job but are unable to find one. In economic language, they are willing to supply labor but cannot find a firm that demands their labor. The most natural starting point for an economic analysis of unemployment is therefore the labor market.

Toolkit: Section 16.1 "The Labor Market"

The labor market brings together the supply of labor by households and the demand for labor by firms. You can review the labor market in the toolkit.

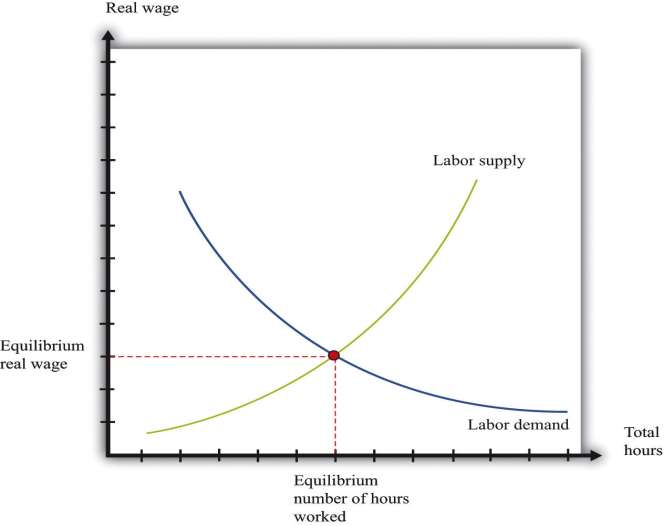

The labor market is depicted in ***Figure 8.3 "Labor Market". “Price” on the vertical axis is the real wage, which is the nominal wage divided by the price level. It tells us how much you can obtain in terms of real goods and services if you sell an hour of your time. Recalling that the price level can be thought of as the price of a unit of the real gross domestic product (real GDP), you can equivalently think of the real wage as the value of your time measured in units of real GDP.

At a higher real wage, households supply more labor. There are two reasons for this. First, a higher real wage means that, for the sacrifice of an hour of time, households can obtain more goods and services than before. Households are therefore induced to substitute away from leisure to work and ultimately consume more. Second, as the wage increases, more individuals join the labor force and find a job. Embedded in the upward-sloping labor supply curve is both an increase in hours worked by each employed worker and an increase in the number of employed workers.

At a higher real wage, firms demand fewer labor hours. A higher real wage means that labor time is more expensive than before, so each individual firm demands less labor and produces less output. The point where the labor supply and demand curves meet is the equilibrium in the labor market. At the equilibrium real wage, the number of hours that workers choose to work exactly matches the number of hours that firms choose to hire.

Supply and demand in the labor market determine the real wage and the level of employment. Variations in either labor supply or labor demand show up as shifts in the curves. If we want to talk about unemployment, however, the labor market diagram presents us with a problem. The idea of a market is that the price adjusts to reach equilibrium—the point where supply equals demand. In the labor market, this means the real wage should adjust to its equilibrium value so that there is no mismatch of supply and demand. Everyone who wants to supply labor at the equilibrium wage finds that their labor is demanded—in other words, everyone who is looking for a job is able to find one.

Remember the definition of unemployment: it is people who are not working but who are looking for a job. The supply-and-demand framework has the implication that there should be no unemployment at all. Everyone who wants to work is employed; the only people without jobs are those who do not want to work.

- 1610 reads