LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After you have read this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

How does the capital stock increase?

What are the factors that lead to output growth?

What are the differences between growth in a closed economy and growth in an open economy?

The macroeconomy is very complicated. Overall economic performance depends on billions of decisions made daily by millions of people. Economists have developed techniques to keep us from being overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the economy and the masses of data that are available to us. One of our favorite devices is to imagine what an economy would look like if it contained only one person. This fiction has two nice features: we do not have to worry about differences among individuals, and we can easily isolate the most important economic decisions. Thinking about the economy as if it were a single person is only a starting point, but it is an extremely useful trick for cutting through all the complexities of, say, a $12 trillion economy populated by 300 million individuals.

Solovenia

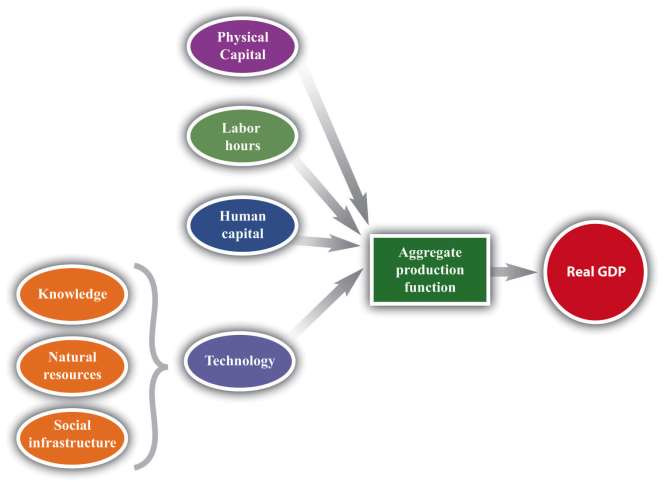

Imagine, then, an economy called Solovenia. Solovenia is populated by one individual—we will call him Juan. Juan has access to an aggregate production function. The amount of output (real GDP) that he can produce depends on how large a physicalcapital stock he owns, how many hours he chooses to work, his human capital, and his technology (***Figure 6.2 "The Aggregate Production Function"). Physical capital is the stock of factories and machinery in the economy, while human capital refers to the skills and education of the workforce. Technology is a catchall term for everything else (other than capital, labor, or human capital) that affects output. [***Physical capital, human capital, and technology are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 "Globalization and Competitiveness".***] It includes the following:

- Knowledge.The technological know-how of the economy

- Social infrastructure.The institutions and social structures that allow a country to produce its real GDP

- Natural resources.The land and mineral resources in the country

Toolkit: Section 16.15 "The Aggregate Production Function"

You can review the aggregate production function, including its inputs, in the toolkit.

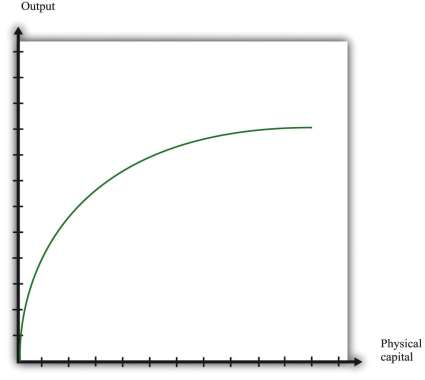

Much of our focus in this chapter is on how economies build up their stock of physical capital. ***Figure 6.3 "The Aggregate Production Function: Output as a Function of the Physical

Capital Stock" shows how output in the aggregate production function depends on the capital stock. Increases in the capital stock lead to more output. If Juan has more tools to work with, then he can produce more goods. However, we usually think that the production function will exhibit diminishing marginal product of capital, which means that a given increase in the capital stock contributes more to output when the capital stock is low than when the capital stock is high. In ***Figure 6.3 "The Aggregate Production Function: Output as a Function of the Physical Capital Stock", we can see this from the fact that the production function gets flatter as the amount of physical capital increases.

Each day Juan chooses how much time to work and how much time to spend in leisure. Other things being equal, we expect that Juan likes to have leisure time. This is not to say that Juan never gets any satisfaction from working. But like most people—even those who enjoy their jobs—he would prefer to work a little bit less and play a little bit more. He cannot spend all his time in leisure, however. He works because he likes to consume. The harder he works, the more real GDP he can produce and consume. Juan’s decision about how many hours to work each day is determined in large part by how productive he can be—that is, how much real GDP he can produce for each hour of leisure time that he gives up.

Juan does not have to consume all the output that he produces; he might save some of it for the future. As well as deciding how much to work, he decides how much to consume and how much to save each day. You have probably made decisions like Juan’s. At some time in your life, you may have worked at a job—perhaps in a fast-food restaurant, a grocery store, or a coffee shop. Perhaps you were paid weekly. Then each week you might have spent all the money you earned on movies, meals out, or clothes. Or—like Juan—you might have decided to spend only some of that money and save some for the future. When you save money instead of spending it, you are choosing to consume goods and services at some future date instead of right now. You may choose to forgo movies and clothes today to save for the purchase of a car or a vacation.

The choice we have just described—consuming versus saving—is one of the most fundamental decisions in macroeconomics. It comes up again and again when we study the macroeconomy. Just as you and Juan make this choice, so does the overall economy. Of course, the economy doesn’t literally make its own decision about how much to save. Instead, the saving decisions of each individual household in the economy determine the overall amount of savings in the economy. And the economy as a whole doesn’t save the way you do—by putting money in a bank. An economy saves by devoting some of its production to capital goods rather than consumer goods. If Juan chooses to produce capital goods, he will have a larger capital stock in the future, which will allow him to be more productive and enjoy higher consumption in the future.

- 5030 reads