The real exchange rate matters because it is the price that is relevant for import and export decisions. Suppose you are trying to decide between buying a mobile phone manufactured in the United States and one manufactured in Finland. If the dollar appreciates against the euro, then the US phone retailer needs fewer dollars to purchase euros, so Finnish phones will be cheaper in US stores. If prices decrease in Finland, the imported phone again becomes relatively cheaper. If prices increase in the United States, the US phone will be more expensive. In other words, increasing prices in the United States, decreasing prices in Finland, and appreciation of the dollar all make you more likely to buy the imported phone rather than the domestically produced phone.

More generally, anything that causes the real exchange rate to increase will make imports look more attractive compared to goods produced in the domestic economy. Examined from the point of view of Europe, the same increase in the real exchange rate makes US goods look more expensive relative to goods produced in Europe, so Europeans will be likely to import fewer goods from the United States. An increase in the real exchange rate therefore leads to an increase in US imports and a decrease in US exports—that is, it leads to a decrease in net exports.

The real exchange rate can and does vary substantially over time. Argentina in the 1990s provides a nice illustration of real exchange rates in action. [***We discuss this in more detail in .***] Argentina had acurrency board during this period. Under a currency board, a country maintains a fixed exchange rate by backing its currency completely with another currency. Although Argentina did have its own currency (the Argentine peso), each peso in circulation was backed by a US dollar held by the Argentine central bank. You could at any time exchange pesos for dollars at a nominal exchange rate of 1.

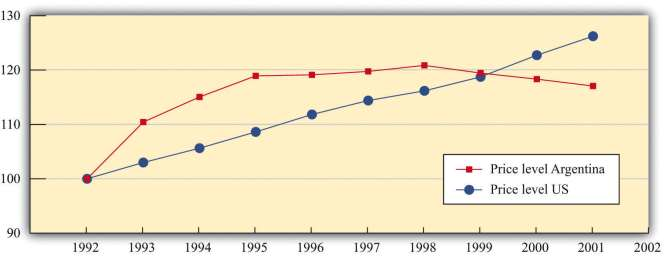

shows what happened to prices in Argentina and the United States over this period. Look at 1992–95. Both countries had some inflation. But prices were increasing faster in Argentina than in the United States. The real exchange rate (Argentina–United States) is given by because the price of the peso in dollars was 1. Therefore the real exchange rate appreciated as Argentine inflation outpaced US inflation.

The appreciation of the real exchange rate meant that Argentine goods became more expensive in other countries, so Argentine exports became less competitive. (The problem was compounded by the fact that the US dollar [and hence the peso] also appreciated against the currencies of neighboring countries such as Brazil.) Without the currency board, it would have been possible for the nominal exchange rate (price of the peso in dollars) to decline, offsetting the effects of the inflation rate. Instead, this appreciation of the real exchange rate ended up causing substantial economic problems in Argentina in the 1990s. In the second half of the decade, the real exchange rate began to depreciate because the inflation rate in Argentina was lower than in the United States. The appreciation at the start of the decade had been so large, however, that the real exchange rate in 1999 was still higher than it had been in 1992.

If countries want to have a permanently fixed exchange rate, there is an option that is more radical than a currency board. Countries can decide to adopt a common currency, like the European countries that adopted the euro. There are several reasons why countries might decide to take such a course of action. The first advantage of a common currency is that it enhances the role of money as a medium of exchange. There is no longer a need to exchange one currency for another, making it easier to trade goods and services across countries. People do not have to deal with the inconveniences of exchanging currencies: individuals do not have to exchange cash at airports, and firms do not need to manage multiple currencies to conduct international business. In the jargon of economics, a single currency removes transaction costs. These costs might be individually small, but they can add up when you consider just how many times households and firms needed to switch from one of the euro area currencies to another.[*** According to studies supporting a common currency, these gains from reduced transactions costs were substantial. One of the key analyses was the Delors report. A summary of that report is available at “Phase 3: the Delors Report,” European Commission, October 30, 2010, accessed August 22, 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/emu/road/delors_report_en.htm. A complete report on the history of the euro is available at “One Currency for One Europe: The Road to the Euro,” European Commission, 2007, accessed August 22, 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication6730_en.pdf. ***]

One way to picture this advantage is to imagine the reverse. Suppose, for example, that each state in the United States decided to adopt its own currency. Trade across state lines would become more complicated and more costly. Even more starkly, imagine that your hometown had its own currency, so you had to exchange money whenever you traveled anywhere else.

A second advantage of a single currency is that it makes business planning easier. A firm in Belgium can write a contract with another firm in Spain without having to worry about the implications of currency appreciation or depreciation. Thus an argument for the move to a single currency was that such a change was likely to encourage trade among countries of the European Union. Again, imagine how much more complicated business would be in the United States if each state had its own freely floating currency. Finally, a common currency enhances capital flows. Just as it is easier for businesses to trade goods and services, it is also easier for investors to shift funds from country to country. With a common currency, investors do not have to pay the transactions costs of converting currencies, and they no longer face the uncertainty of exchange rate changes. When capital flows more easily across borders, investment activity is more productive, enhancing the growth of the countries involved.

KEY TAKEAWAY

The nominal exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another. The real exchange rate compares the price of goods and services in one country to the cost of these goods and services in another country when all prices are in a common currency.

From the law of one price, a tradable good in one country should have the same price as that same good in another country when the goods are priced in the same currency. This means that the exchange rate is equal to the ratio of the prices expressed in the two different currencies. Put differently, by the law of one price, the real exchange rate between tradable goods should be 1.

****

Checking Your Understanding

If the price of a euro was $2 and the price of a dollar was 1 EUR, how would you make a profit?

If goulash sells for either 1,090 forint or 4.40 euro, what is the price of the forint in terms of the euro? Do the two prices of cabbage quoted in yield a different euro price for the forint? Is there an arbitrage possibility here (or elsewhere on the menu)?

- 2722 reads