Why are we so interested in the accumulation of capital? One reason is that poverty of the kind we observe in Niger and elsewhere is a massive problem for the world. About 40 percent of the world’s population—close to 2.5 billion people—live in conditions of poverty. (The World Bank defines poverty as living on less than US$2 per day.) We are not going to solve the problem of mass poverty overnight, so we would like to know whether this gap between the rich and the poor is a permanent feature of the world. It might be that economies will diverge, meaning that the disparities in living standards will get worse and worse, or it might be that they will converge, with poorer countries catching up to richer countries.

When comparing two countries, if we find that the poorer economy is growing faster than the richer one, then the two are converging. If we find that the richer country is growing faster than the poorer one, they are diverging. Moreover, if a country has a small capital stock, we know that—other things being equal—it will tend to be a poorer country. If a country has a large capital stock, then—again, other things being equal—it is likely to be a richer country. The question of convergence then becomes: other things being equal, do we expect a country with a small capital stock to grow faster than an economy with a large capital stock?

The answer is yes, and the reason is the marginal product of capital. From the production function, the marginal product of capital is large when the capital stock is small. Think again about Juan in Solovenia. A large marginal product of capital means that he can obtain a lot of extra output if he acquires some extra capital. This gives him an incentive to save rather than consume. A large marginal product of capital also means that Juan can attract investment from other countries.

A country where the marginal product of capital is high is a competitive economy—one where both domestic savers and foreign savers want to build up the capital stock. The capital stock will grow quickly in such an economy. This is precisely what we saw in the equation for the growth rate of the capital stock: higher investment and a lower capital stock both lead to a larger capital stock growth rate. Both of these imply that a country with a large marginal product of capital will tend to grow fast.

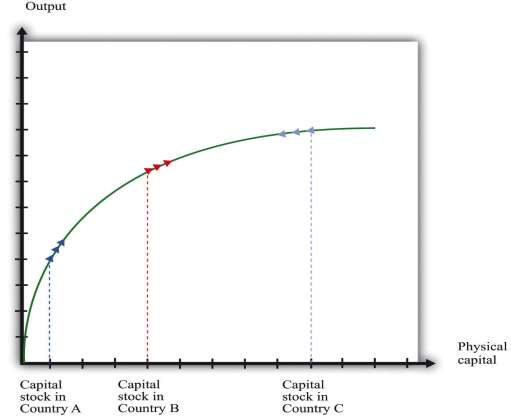

We illustrate this idea in ***Figure 6.8 "Convergence through the Accumulation of Capital". Country A has a small capital stock. The aggregate production function tells us that this translates into a large marginal product of capital—the production function is steep. In turn, a large marginal product of capital means that country A will grow quickly. Country B has an identical production function but a larger capital stock, so the marginal product of capital is lower in country B than in country A. There is less incentive to invest, implying that country B, while richer than country A, grows more slowly.

***Figure 6.8 "Convergence through the Accumulation of Capital" also shows that it is possible for a country to have such a large capital stock that it shrinks rather than grows. Country C has so much capital that its marginal product is very low. There is little incentive to build up the capital stock, so the capital stock depreciates faster than it is replaced by new investment. In such an economy, the capital stock and output would decrease over time.

***Figure 6.8 "Convergence through the Accumulation of Capital" suggests an even stronger conclusion: all three economies will ultimately end up at the same capital stock and the same level of output—complete convergence. This conclusion is half right. If the three economies were identical except for their capital stocks and if there were no growth in human capital and technology, they would indeed converge to exactly the same level of capital stock and output. In Section 6.4 "Balanced Growth", we look at this argument more carefully. First, though, we examine the evidence on convergence.

- 1803 reads