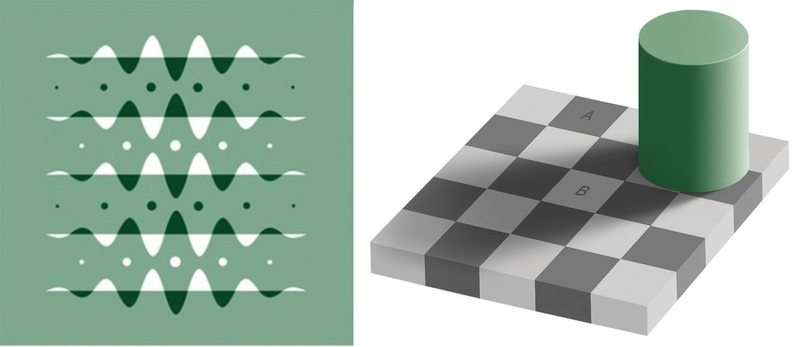

Although our perception is very accurate, it is not perfect. Illusions occur when the perceptual processes that normally help us correctly perceive the world around us are fooled by a particular situation so that we see something that does not exist or that is incorrect. Figure 4.17 presents two situations in which our normally accurate perceptions of visual constancy have been fooled.

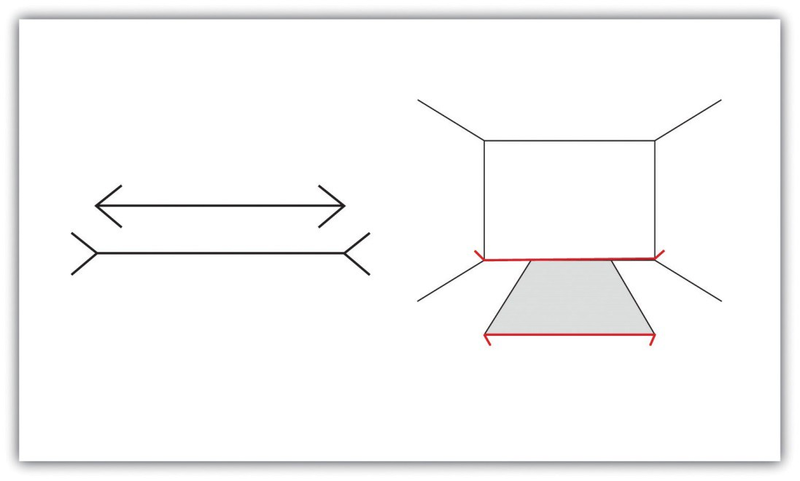

Another well-known illusion is the Mueller-Lyer illusion (see Figure 4.18). The line segment in the bottom arrow looks longer to us than the one on the top, even though they are both actually the same length. It is likely that the illusion is, in part, the result of the failure of monocular depth cues—the bottom line looks like an edge that is normally farther away from us, whereas the top one looks like an edge that is normally closer.

The moon illusion refers to the fact that the moon is perceived to be about 50% larger when it is near the horizon than when it is seen overhead, despite the fact that both moons are the same size and cast the same size retinal image. The monocular depth cues of position and aerial perspective create the illusion that things that are lower and more hazy are farther away. The skyline of the horizon (trees, clouds, outlines of buildings) also gives a cue that the moon is far away, compared to a moon at its zenith. If we look at a horizon moon through a tube of rolled up paper, taking away the surrounding horizon cues, the moon will immediately appear smaller.

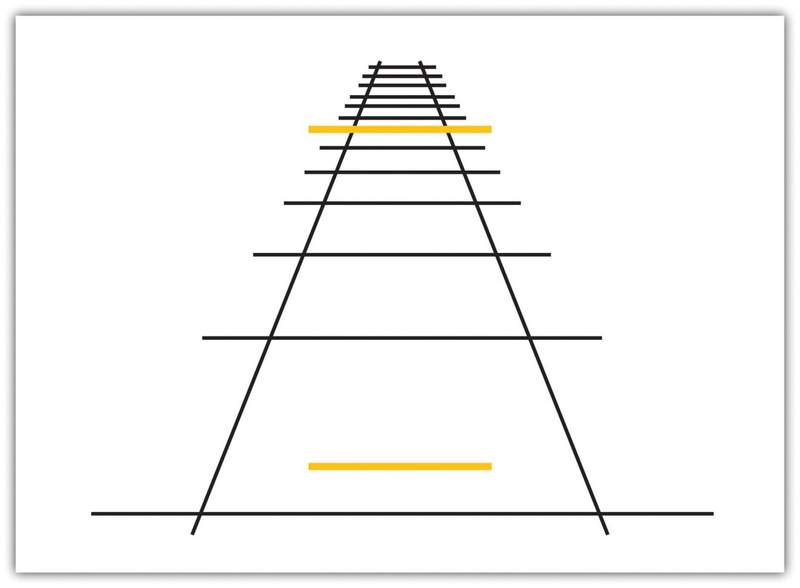

The Ponzo illusion operates on the same principle. As you can see in Figure 4.19, the top yellow bar seems longer than the bottom one, but if you measure them you’ll see that they are exactly the same length. The monocular depth cue of linear perspective leads us to believe that, given two similar objects, the distant one can only cast the same size retinal image as the closer object if it is larger. The topmost bar therefore appears longer.

Illusions demonstrate that our perception of the world around us may be influenced by our prior knowledge. But the fact that some illusions exist in some cases does not mean that the perceptual system is generally inaccurate—in fact, humans normally become so closely in touch with their environment that that the physical body and the particular environment that we sense and perceive becomes embodied—that is, built into and linked with—our cognition, such that the worlds around us become part of our brain (Calvo & Gamila, 2008). 1 The close relationship between people and their environments means that, although illusions can be created in the lab and under some unique situations, they may be less common with active observers in the real world (Runeson, 1988). 2

- 3784 reads