Was Kitty Genovese murdered because there were too many people who heard her cries? Watch this video for a n analysis.

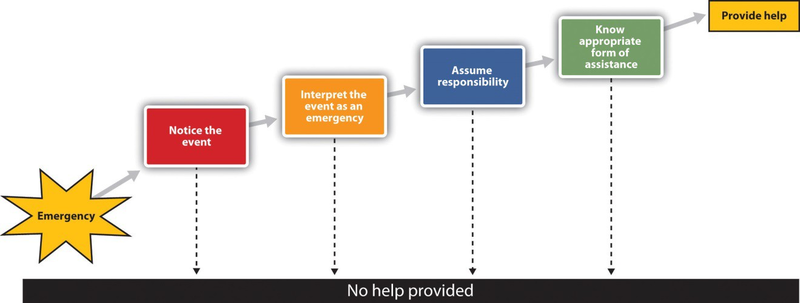

Two social psychologists, Bibb Latané a nd John Darley, were interested in the factors that influenced people to help (or to not help) in such situations (Latané & Darley, 1968). 1 They developed a model (see Figure 14.3) that took into consideration the important role of the social situation in determining helping. The model has been extensively tested in many studies, and there is substantial support for it. Social psychologists have discovered that it was the 38 people themselves that contributed to the tragedy, because people are less likely to notice, interpret, and respond to the needs of others when they are with others than they are when they are alone.

The first step in the model is noticing the event. Latané and Darley (1968) 2 demonstrated the important role of the social situation in noticing by asking research participants to complete a questionnaire in a small room. Some of the participants completed the questionnaire alone, whereas others completed the questionnaire in small groups in which two other participants were also working on questionnaires. A few minutes after the participants had begun the questionnaires, the experimenters started to let some white smoke come into the room through a vent in the wall. The experimenters timed how long it took before the first person in the room looked up and noticed the smoke.

The people who were working alone noticed the smoke in about 5 seconds, and within 4 minutes most of the participants who were working alone had taken some action. On the other hand, on average, the first person in the group conditions did not notice the smoke until over 20 seconds had elapsed. And, although 75% of the participants who were working alone reported the smoke within 4 minutes, the smoke was reported in only 12% of the groups by that time. In fact, in only 3 of the 8 groups did anyone report the smoke, even after it had filled the room. You can see that the social situation has a powerful influence on noticing; we simply don’t see emergencies when other people are with us.

Even if we notice a n emergency, we might not interpret it as one. Were the cries of Kitty Genovese really calls for help, or were they simply an argument with a boyfriend? The problem is compounded when others are present, because when we are unsure how to interpret events we normally look to others to help us understand them, and at the same time they are looking to us for information. The problem is that each bystander thinks that other people aren’t acting because they don’t see an emergency. Believing that the others know something that they don’t, each observer concludes that help is not required.

Even if we have noticed the emergency and interpret it as being one, this does not necessarily mean that we will come to the rescue of the other person. We still need to decide that it is our responsibility to do something. The problem is that when we see others around, it is easy to assume that they are going to do something, and that we don’t need to do anything ourselves. Diffusion of responsibility occurs whenweassumethat others will takeaction and thereforewedo not take action ourselves. The irony again, of course, is that people are more likely to help when they are the only ones in the situation than when there are others around.

Perhaps you have noticed diffusion of responsibility if you participated in an Internet users group where people asked questions of the other users. Did you find that it was easier to get help if you directed your request to a smaller set of users than when you directed it to a larger number of people? Markey (2000) 3 found that people received help more quickly (in about 37 seconds) when they asked for help by specifying a participant’s name than when no name was specified (51 seconds).

The final step in the helping model is knowing how to help. Of course, for many of us the ways to best help another person in an emergency are not that clear; we are not professionals and we have little training in how to help in emergencies. People who do have training in how to act in emergencies are more likely to help, whereas the rest of us just don’t know what to do, and therefore we may simply walk by. On the other hand, today many people have cell phones, and we can do a lot with a quick call; in fact, a phone call made in time might have saved Kitty Genovese’s life.

- 2609 reads