A psychological disorder is an ongoing dysfunctional pattern of thought, emotion, and behavior that causes significant distress, and that is considered deviant in that person’s culture or society (Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007). 1 Psychological disorders have much in common with other medical disorders. They are out of the patient’s control, they may in some cases be treated by drugs, and their treatment is often covered by medical insurance. Like medical problems, psychological disorders have both biological (nature) a s well as environmental (nurture) influences. These causal influences are reflected in the bio-psycho-social model of illness (Engel, 1977). 2

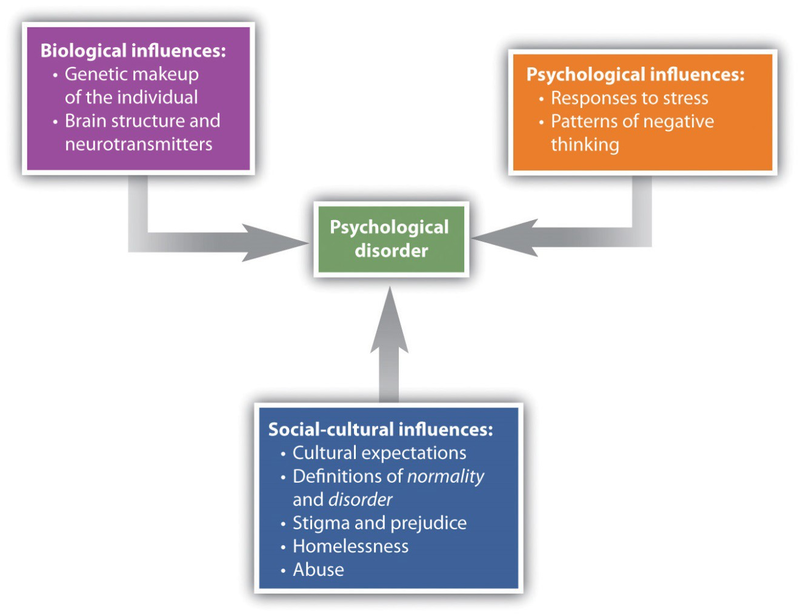

The bio-psycho-social model of illness is a wayof understanding disorder that assumes that disorder is caused bybiological, psychological, and social factors (Figure 12.1). The biological componentof the bio-psycho-social model refers to the influences on disorder that come from the functioning of the individual’s body. Particularly important are genetic characteristics that make some people more vulnerable to a disorder than others and the influence of neurotransmitters. The psychological component of the bio-psycho- social model refers to the influences that come from the individual, such as patterns of negative thinking and stress responses. The social component of the bio-psycho-social model refers to the influences on disorder due to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, homelessness, abuse, and discrimination.

To consider one example, the psychological disorder of schizophrenia has a biological cause because it is known that there are patterns of genes that make a person vulnerable to the disorder (Gejman, Sanders, & Duan, 2010). 3 But whether or not the person with a biological vulnerability experiences the disorder depends in large part on psychological factors such as how the individual responds to the stress he experiences, as well as social factors such as whether or not he is exposed to stressful environments in adolescence and whether or not he has support from people who care about him (Sawa & Snyder, 2002; Walker, Kestler, Bollini, & Hochman, 2004). 4 Similarly, mood and anxiety disorders are caused in part by genetic factors such as hormones and neurotransmitters, in part by the individual’s particular thought patterns, and in part by the ways that other people in the social environment treat the person with the disorder.

We will use the bio-psycho-social model as a framework for considering the causes and treatments of disorder.

Although they share many characteristics with them, psychological disorders are nevertheless different from medical conditions in important ways. For one, diagnosis of psychological disorders can be more difficult. Although a medical doctor can see cancer in the lungs using an MRI scan or see blocked arteries in the heart using cardiac catheterization, there is no corresponding test for psychological disorder. Current research is beginning to provide more evidence about the role of brain structures in psychological disorder, but for now the brains of people with severe mental disturbances often look identical to those of people without such disturbances.

Because there are no clear biological diagnoses, psychological disorders are instead diagnosed on the basis of clinical observations of the behaviors that the individual engages in. These observations find that emotional states and behaviors operate on a continuum, ranging from more “normal” and “accepted” to more “deviant,” “abnormal,” a nd “unaccepted.” The behaviors that are associated with disorder are in many cases the same behaviors we that engage in our “normal” everyday life. Washing one’s hands is a normal healthy activity, but it can be overdone by those with an obsessive-compulsive disorder(OCD). It is not unusual to worry about and try to improve one’s body image, but Robert’s struggle with his personal appearance, as discussed at the beginning of this chapter, was clearly unusual, unhealthy, and distressing to him.

Whether a given behavior is considered a psychological disorder is determined not only by whether a behavior is unusual (e.g., whether it is “mild” anxiety versus “extreme” anxiety) but also by whether a behavior is maladaptive—that is, the extent to which it causes distress (e.g., pain and suffering) a nd dysfunction (impairment in one or more important areas of functioning) to the individual (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). 5 An intense fear of spiders, for example, would not be considered a psychological disorder unless it has a significant negative impact on the sufferer’s life, for instance by causing him or her to be unable to step outside the house. The focus on distress and dysfunction means that behaviors that are simply unusual (such as some political, religious, or sexual practices) are not classified as disorders.

Put your psychology hat on for a moment and consider the behaviors of the people listed in Table 12.2. For each, indicate whether you think the behavior is or is not a psychological disorder. If you’re not sure, what other information would you need to know to be more certain of your diagnosis?

|

Yes |

No |

Needmore information |

Description |

|

Jackie frequently talks to herself while she is working out her math homework. Her roommate sometimes hears her and wonders if she is OK. |

|||

|

Charlie believes that the noises made by cars and planes going by outside his house have secret meanings. He is convinced that he was involved in the start of a nuclear war and that the only way for him to survive is to find the answer to a difficult riddle. |

|||

|

Harriet gets very depressed during the winter months when the light is low. She sometimes stays in her pajamas for the whole weekend, eating chocolate and watching TV. |

|||

|

Frank seems to be afraid of a lot of things. He worries about driving on the highway and about severe weather that may come through his neighborhood. But mostly he fears mice, checking under his bed frequently to see if any are present. |

|||

|

A worshipper speaking in “tongues” at an Evangelical church views himself as “filled” with the Holy Spirit and is considered blessed with the gift to speak the “language of angels.” |

A trained clinical psychologist would have checked off “need more information” for each of the examples in Table 12.2 because although the behaviors may seem unusual, there is no clear evidence that they are distressing or dysfunctional for the person. Talking to ourselves out loud is unusual and can be a symptom of schizophrenia, but just because we do it once in a while does not mean that there is anything wrong with us. It is natural to be depressed, particularly in the long winter nights, but how severe should this depression be, and how long should it last? If the negative feelings last for a n extended time and begin to lead the person to miss work or classes, then they may become symptoms of a mood disorder. It is normal to worry about things, but when does worry turn into a debilitating anxiety disorder? And what about thoughts that seem to be irrational, such as being able to “speak the language of angels”? Are they indicators of a severe psychological disorder, or part of a normal religious experience? Again, the answer lies in the extent to which they are (or are not) interfering with the individual’s functioning in society.

Another difficulty in diagnosing psychological disorders is that they frequently occur together. For instance, people diagnosed with anxiety disorders also often have mood disorders (Hunt, Slade, & Andrews, 2004), 6 and people diagnosed with one personality disorder frequently suffer from other personality disorders as well. Comorbidity occurs when peoplewho suffer from onedisorder also suffer at thesametimefrom other disorders. Because many psychological disorders are comorbid, most severe mental disorders are concentrated in a small group of people (about 6% of the population) who have more than three of them (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). 7

Psychology in Everyday Life: Combating the Stigma of Abnormal Behavior

Every culture and society has its own views on what constitutes abnormal behavior and what causes it (Brothwell, 1981). 8 The Old Testament Book of Samuel tells us that as a consequence of his sins, God sent

King Saul an evil spirit to torment him (1 Samuel 16:14). Ancient Hindu tradition attributed psychological disorder to sorcery and witchcraft. During the Middle Ages it was believed that

mental illness occurred when the body was infected by evil spirits, particularly the devil. Remedies included whipping, bloodletting, purges, and trepanation (cutting a hole in the skull) to

release the demons.

Until the 18th century, the most common treatment for the mentally ill was to incarcerate them in asylums or “madhouses.” During the 18th century, however, some reformers began to oppose this brutal treatment of the mentally ill, arguing that mental illness was a medical problem that had nothing to do with evil spirits or demons. In France, one of the key reformers was Philippe Pinel (1745–1826), who believed that mental illness was caused by a combination of physical and psychological stressors, exacerbated by inhumane c onditions. Pinel advocated the introduction of exercise, fresh air, and daylight for the inmates, as well as treating them gently and talking with them. In America, the reformers Benjamin Rush (1745–1813) and Dorothea Dix (1802–1887) were instrumental in creating mental hospitals that treated patients humanely and attempted to cure them if possible. These reformers saw mental illness as an underlying psychological disorder, which was diagnosed according to its symptoms and which could be cured through treatment.

Despite the progress made since the 1800s in public attitudes about those who suffer from psychological disorders, people, including police, coworkers, and even friends and family members, still stigmatize people with psychological disorders. A stigma refers to a disgrace or defect that indicates that person belongs to a culturally devalued social group. In some cases the stigma of mental illness is accompanied by the use of disrespectful and dehumanizing labels, including names such as “crazy,” “nuts,” “mental,” “schizo,” and “retard.”

The stigma of mental disorder affects people while they are ill, while they are healing, and even after they have healed (Schefer, 2003). 9 On a community level, stigma can affect the kinds of services social service agencies give to people with mental illness, and the treatment provided to them and their families by schools, workplaces, places of worship, and health-care providers. Stigma about mental illness also leads to employment discrimination, despite the fact that with appropriate support, even people with severe psychological disorders are able to hold a job (Boardman, Grove, Perkins, & Shepherd, 2003; Leff & Warner, 2006; Ozawa & Yaeda, 2007; Pulido, Diaz, & Ramirez, 2004). 10

The mass media has a significant influence on society’s attitude toward mental illness (Francis, Pirkis, Dunt, & Blood, 2001). 11 While media portrayal of mental illness is often sympathetic, negative stereotypes still remain in newspapers, magazines, film, and television. (See the following video for an example.)

Television advertisements may perpetuate negative stereotypes about the mentally ill. Burger King recently ran an ad called “The King’s Gone Crazy,” in which the company’s mascot runs around an office complex carrying out acts of violence and wreaking havoc.

The most significant problem of the stigmatization of those with psychological disorder is that it slows their recovery. People with mental problems internalize societal attitudes about mental illness, often becoming so embarrassed or ashamed that they conceal their difficulties and fail to seek treatment. Stigma leads to lowered self-esteem, increased isolation, and hopelessness, and it may negatively influence the individual’s family and professional life (Hayward & Bright, 1997). 12

Despite all of these challenges, however, many people overcome psychological disorders and go on to lead productive lives. It is up to all of us who are informed about the causes of psychological disorder and the impact of these conditions on people to understand, first, that mental illness is not a “fault” any more than is cancer. People do not choose to have a mental illness. Second, we must all work to help overcome the stigma associated with disorder. Organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI; n.d.), 13 for example, work to reduce the negative impact of stigma through education, community action, individual support, and other techniques.

- 5142 reads