LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Summarize the ways that scientists evaluate the effectiveness of psychological, behavioral, and community service approaches to preventing and reducing disorders.

- Summarize which types of therapy are most effective for which disorders.

We have seen that psychologists and other practitioners employ a variety of treatments in their attempts to reduce the negative outcomes of psychological disorders. But we have not yet considered the important question of whether these treatments are effective, and if they are, which approaches are most effective for which people a nd for which disorders. Accurate empirical answers to these questions are important as they help practitioners focus their efforts on the techniques that have been proven to be most promising, and will guide societies as they make decisions about how to spend public money to improve the quality of life of their citizens (Hunsley & Di Giulio, 2002). 1

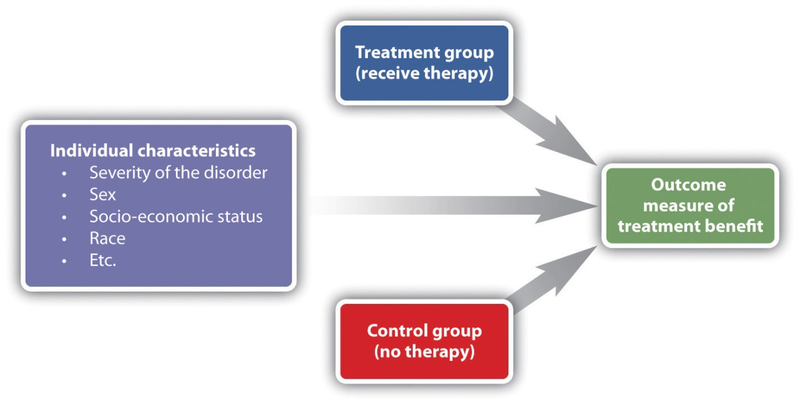

Psychologists use outcome research, that is, studies that assess the effectiveness of medical treatments, to determine the effectiveness of different therapies. As you can see in Figure 13.5, in these studies the independent variable is the type of the treatment—for instance, whether it was psychological or biological in orientation or how long it lasted. In most cases characteristics of the client (e.g., his or her gender, age, disease severity, and prior psychological histories) are a lso collected as control variables. The dependent measure is an assessment of the benefit received by the client. In some cases we might simply ask the client if she feels better, and in other cases we may directly measure behavior: Can the client now get in the airplane and take a flight? Has the client remained out of juvenile detention?

In every case the scientists evaluating the therapy must keep in mind the potential that other effects rather than the treatment itself might be important, that some treatments that seem effective might not be, and that some treatments might actually be harmful, at least in the sense that money and time are spent on programs or drugs that do not work.

One threat to the validity of outcome research studies is natural improvement—the possibility that people might get better over time, even without treatment. People who begin therapy or join a self-help group do so because they are feeling bad or engaging in unhealthy behaviors. After being in a program over a period of time, people frequently feel that they are getting better. But it is possible that they would have improved even if they had not attended the program, and that the program is not actually making a difference. To demonstrate that the treatment is effective, the people who participate in it must be compared with another group of people who do not get treatment.

Another possibility is that therapy works, but that it doesn’t really matter which type of therapy it is. Nonspecifictreatment effects occur when the patient gets better over time simply by coming to therapy, even though it doesn’t matter what actually happens at the therapy sessions. The idea is that therapy works, in the sense that it is better than doing nothing, but that all therapies are pretty much equal in what they are able to accomplish. Finally, placeboeffects are improvements that occur as a result of the expectation that one will get better rather than from the actual effects of a treatment.

- 3641 reads