One challenge to the trait approach to personality is that traits may not be as stable as we think they are. When we say that Malik is friendly, we mean that Malik is friendly today and will be friendly tomorrow and even next week. And we mean that Malik is friendlier than average in all situations. But what if Malik were found to behave in a friendly way with his family members but to be unfriendly with his fellow classmates? This would clash with the idea that traits are stable across time and situation.

The psychologist Walter Mischel (1968) 1 reviewed the existing literature on traits and found that there was only a relatively low correlation (about r = .30) between the traits that a person expressed in one situation and those that they expressed in other situations. In one relevant study, Hartshorne, May, Maller, & Shuttleworth (1928) 2] examined the correlations among various behavioral indicators of honesty in children. They also enticed children to behave either honestly or dishonestly in different situations, for instance, by making it easy or difficult for them to steal and cheat. The correlations among children’s behavior was low, generally less than r = .30, showing that children who steal in one situation are not always the same children who steal in a different situation. And similar low correlations were found in adults on other measures, including dependency, friendliness, and conscientiousness (Bem & Allen, 1974). 3

Psychologists have proposed two possibilities for these low correlations. One possibility is that the natural tendency for people to see traits in others leads us to believe that people have stable personalities when they really do not. In short, perhaps traits are more in the heads of the people who are doing the judging than they are in the behaviors of the people being observed. The fact that people tend to use human personality traits, such as the Big Five, to judge animals in the same way that they use these traits to judge humans is consistent with this idea (Gosling, 2001). 4 And this idea a lso fits with research showing that people use their knowledge representation (schemas) about people to help them interpret the world around them and that these schemas color their judgments of others’ personalities (Fiske & Taylor, 2007). 5

Research has also shown that people tend to see more traits in other people than they do in themselves. You might be able to get a feeling for this by taking the following short quiz. First, think about a person you know—your mom, your roommate, or a classmate—and choose which of the three responses on each of the four lines best describes him or her. Then answer the questions again, but this time about yourself.

|

1. |

Energetic |

Relaxed |

Depends on the situation |

|

2. |

Skeptical |

Trusting |

Depends on the situation |

|

3. |

Quiet |

Talkative |

Depends on the situation |

|

4. |

Intense |

Calm |

Depends on the situation |

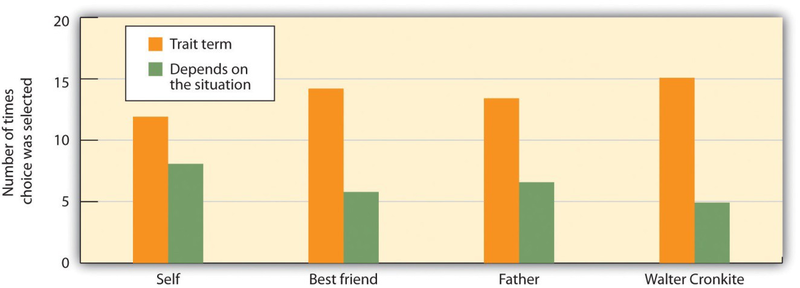

Richard Nisbett and his colleagues (Nisbett, Caputo, Legant, & Marecek, 1973) 6 had college students complete this same task for themselves, for their best friend, for their father, and for the (at the time well-known) newscaster Walter Cronkite. As you can see in Figure 11.3, the participants chose one of the two trait terms more often for other people than they did for themselves, and chose “depends on the situation” more frequently for themselves than they did for the other people. These results also suggest that people may perceive more consistent traits in others than they should.

The human tendency to perceive traits is so strong that it is very easy to convince people that trait descriptions of themselves are accurate. Imagine that you had completed a personality test and the psychologist administering the measure gave you this description of your personality:

You havea great need for other peopleto likeandadmire you. You havea tendencyto be critical of yourself. You havea great deal of unused capacity, which you havenot turned to your advantage.While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

I would imagine that you might find that it described you. You probably do criticize yourself at least sometimes, and you probably do sometimes worry about things. The problem is that you would most likely have found some truth in a personality description that was the opposite. Could this description fit you too?

Youfrequentlystand up for your own opinions even if it means that others may judge you negatively. You have a tendency to find the positives in your own behavior.You work to the fullest extent of your capabilities.You have few personality weaknesses, but some may show up under stress. You sometimes confidein others that you are concerned or worried, but inside you maintain disciplineand self-control. You generally believe that you have made the right decision and done the right thing.

The Barnum effect refers to theobservation that peopletend to believein descriptions of their personality that supposed lyared escriptive of them but could in fact describe almost anyone. The Barnum effect helps us understand why many people believe in astrology, horoscopes, fortune- telling, palm reading, tarot card reading, and even some personality tests. People are likely to accept descriptions of their personality if they think that they have been written for them, even though they cannot distinguish their own tarot card or horoscope readings from those of others at better than chance levels (Hines, 2003). 7 Again, people seem to believe in traits more than they should.

A second way that psychologists responded to Mischel’s findings was by searching even more carefully for the existence of traits. One insight was that the relationship between a trait and a behavior is less than perfect because people can express their traits in different ways (Mischel & Shoda, 2008). 8People high in extraversion, for instance, may become teachers, salesmen, actors, or even criminals. Although the behaviors are very different, they nevertheless all fit with the meaning of the underlying trait.

Psychologists also found that, because people do behave differently in different situations, personality will only predict behavior when the behaviors are aggregated or averaged across different situations. We might not be able to use the personality trait of openness to experience to determine what Saul will do on Friday night, but we can use it to predict what he will do over the next year in a variety of situations. When many measurements of behavior are combined, there is much clearer evidence for the stability of traits and for the effects of traits on behavior (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000; Srivastava, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2003). 9

Taken together, these findings make a very important point about personality, which is that it not only comes from inside us but is also shaped by the situations that we are exposed to. Personality is derived from our interactions with and observations of others, from our interpretations of those interactions and observations, and from our choices of which social situations we prefer to enter or a void (Bandura, 1986). 10 In fact, behaviorists such as B. F. Skinner explain personality entirely in terms of the environmental influences that the person has experienced. Because we are profoundly influenced by the situations that we ar e exposed to, our behavior does change from situation to situation, making personality less stable than we might expect. And yet personality does matter—we can, in many cases, use personality measures to predict behavior across situations.

- 14109 reads