Newborns are already prepared to face the new world they are about to experience. As you can see in Table 6.2, babies are equipped with a variety of reflexes, each providing an ability that will help them survive their first few months of life as they continue to learn new routines to help them survive in and manipulate their environments.

|

Name |

Stimulus |

Response |

Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rooting reflex |

The baby’s cheek is stroked. |

The baby turns its head toward the stroking, opens its mouth, and tries to suck. |

Ensures the infant’s feeding will be a reflexive habit |

|

Blink reflex |

A light is flashed in the baby’s eyes. |

The baby closes both eyes. |

Protects eyes from strong and potentially dangerous stimuli |

|

Withdrawal reflex |

A soft pinprick is applied to the sole of the baby’s foot. |

The baby flexes the leg. |

Keeps the exploring infant away from painful stimuli |

|

Tonic neck reflex |

The baby is laid down on its back. |

The baby turns its head t o one side and extends the arm on the same side. |

Helps develop hand-eye coordination |

|

Grasp reflex |

An object is pressed into the palm of the baby. |

The baby grasps the object pressed and can even hold its own weight for a brief period. |

Helps in exploratory learning |

|

Moro reflex |

Loud noises or a sudden drop in height while holding the baby. |

The baby extends arms and legs and quickly brings them in as if trying to grasp something. |

Protects from falling; could have assisted infants in holding onto their mothers during rough traveling |

|

Stepping reflex |

The baby is suspended with bare feet just above a surface and is moved forward. |

Baby makes stepping motions as if trying to walk. |

Helps encourage motor development |

In addition to reflexes, newborns have preferences—they like sweet tasting foods at first, while becoming more open to salty items by 4 months of age (Beauchamp, Cowart, Menellia, & Marsh, 1994; Blass & Smith, 1992). 1 Newborns also prefer the smell of their mothers. An infant only 6 days old is significantly more likely to turn toward its own mother’s breast pad than to the breast pad of another baby’s mother (Porter, Makin, Davis, & Christensen, 1992), 2 and a newborn also shows a preference for the face of its own mother (Bushnell, Sai, & Mullin,1989). 3

Although infants are born ready to engage in some activities, they also contribute to their own development through their own behaviors. The child’s knowledge a nd abilities increase as it babbles, talks, crawls, tastes, grasps, plays, and interacts with the objects in the environment (Gibson, Rosenzweig, & Porter, 1988; Gibson & Pick, 2000; Smith & Thelen, 2003). 4 Parents may help in this process by providing a variety of activities and experiences for the child. Research has found that animals raised in environments with more novel objects and that engage in a variety of stimulating activities have more brain synapses and larger cerebral cortexes, and they perform better on a variety of learning tasks compared with animals raised in more impoverished environments (Juraska, Henderson, & Müller, 1984). 5 Similar effects are likely occurring in children who have opportunities to play, explore, and interact with their environments (Soska, Adolph, & Johnson, 2010). 6

Research Focus: Using the Habituation Technique to Study What Infants Know

It may seem to you that babies have little ability to view, hear, understand, or remember the world around them. Indeed, the famous psychologist William James presumed that the newborn experiences a “blooming, buzzing confusion” (James, 1890, p. 462). 7 And you may think that, even if babies do know more than James gave them credit for, it might not be possible to find out what they know. After all, infants can’t talk or respond to questions, so how would we ever find out? But over the past two decades, developmental psychologists have created new ways to determine what babies know, and they have found that they know much more than you, or William James, might have expected.

One w ay that we can learn about the cognitive development of babies is by measuring their behavior in response to the stimuli around them. For instance, some researchers have given babies the chance to control w hich shapes they get to see o r which sounds they get to hear according to how hard they suck on a pacifier (Trehub & Rabinovitch, 1972). 8 The sucking behavior is used as a measure of the infants’ interest in the stimuli—the sounds or images they suck hardest in response to are the one s we can assume they prefer.

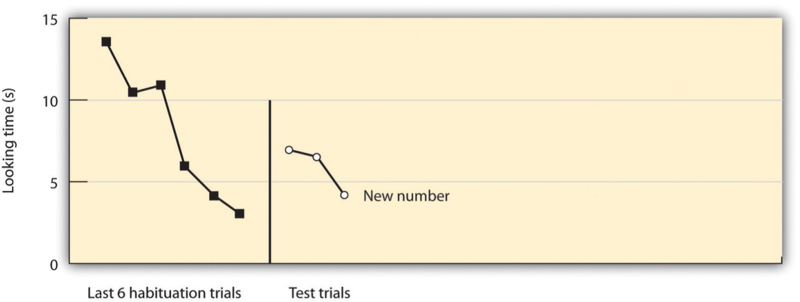

Another approach to understanding cognitive development by observing the behavior of infants is through the use of the habituation technique. Habituation refers to the decreased responsiveness toward a stimulus after it has been presented numerous times in succession. Organisms, including infants, tend to be more interested in things the first few times they experience them and become less interested in them with more frequent exposure. Developmental psychologists have used this general principle to help them understand what babies remember and understand. In the habituation procedure, a baby is placed in a high chair and presented with visual stimuli while a video camera records the infant’s eye and face movements. When the experiment begins, a stimulus (e.g., the face of an adult) appears in the baby’s field of view, and the amount of time the baby looks at the face is recorded by the camera. Then the stimulus is removed for a few seconds before it appears again and the gaze is again measured. Over time, the baby starts to habituate to the face, such that each presentation elicits less gazing at the stimulus. Then, a new stimulus (e.g., the face of a different adult or the same face looking in a different direction) is presented, and the researchers observe whether the gaze time significantly increases. You can see that, if the infant’s gaze time increases when a new stimulus is presented, this indicates that the baby can differentiate the two stimuli.

Although this procedure is very simple, it allows researchers to create variations that reveal a great deal about a newborn’s cognitive ability. The trick is simply to change the stimulus in

controlled ways to see if the baby “notices the difference.” Research using the habituation procedure has found that babies can notice changes in colors, sounds, and even principles of

numbers and physics. For instance, in one experiment reported by Karen Wynn (1995), 9 6- month-old babies were shown a presentation of a puppet that repeatedly jumped up and down either two or three times, resting

for a couple of seconds between sequences (the length of time and the speed of the jumping were controlled). After the infants habituated to this display, the presentation was changed such

that the puppet jumped a different number of times. As you can see in Figure 6.1, the infants’ gaze time increased when Wynn changed the presentation, suggesting that the infants could tell the difference between the number of

jumps.

Karen Wynn found that babies that had habituated to a puppet jumping either two or three times significantly increased their gaze when the puppet began to jump a different number of times.

- 4723 reads