Although it is less common in the United States than in other countries,bilingualism (theability to speaktwo languages) is becoming more and more frequent in the modern world. Nearly one- half of the world’s population, including 18% of U.S. citizens, grows up bilingual.

In recent years many U.S. states have passed laws outlawing bilingual education in schools. These laws are in part based on the idea that students will have a stronger identity with the school, the culture, and the government if they speak only English, and in part based on the idea that speaking two languages may interfere with cognitive development.

Some early psychological research showed that, when compared with monolingual children, bilingual children performed more slowly when processing language, and their verbal scores were lower. But these tests were frequently given in English, even when this was not the child’s first language, and the children tested were often of lower socioeconomic status than the monolingual children (Andrews, 1982). 1

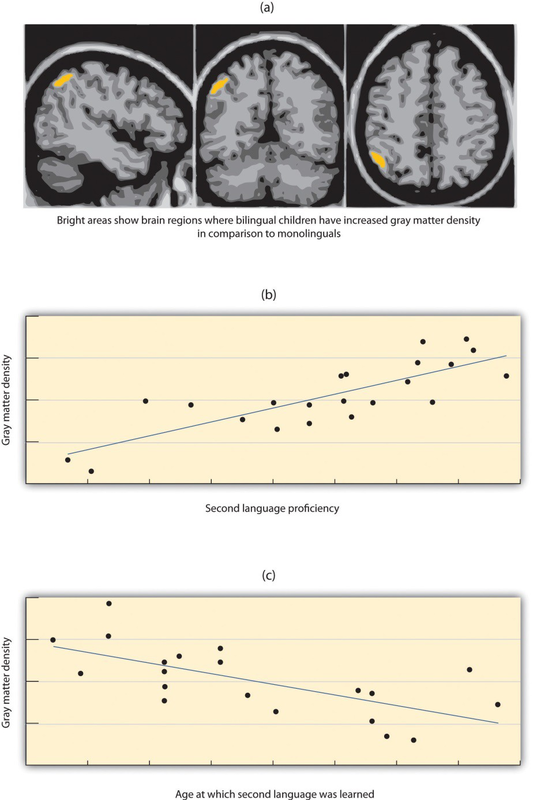

More current research that has controlled for these factors has found that, although bilingual children may in some cases learn language somewhat slower than do monolingual children (Oller & Pearson, 2002), 2 bilingual and monolingual children do not significantly differ in the final depth of language learning, nor do they generally confuse the two languages (Nicoladis & Genesee, 1997). 3 In fact, participants who speak two languages have been found to have better cognitive functioning, cognitive flexibility, and analytic skills in comparison to monolinguals (Bialystok, 2009). 4 Research (Figure 9.9) has also found that learning a second language produces changes in the area of the brain in the left hemisphere that is involved in language, such that this area is denser a nd contains more neurons (Mechelli et al., 2004). 5 Furthermore, the increased density is stronger in those individuals who are most proficient in their second language and who learned the second language earlier. Thus, rather than slowing language development, learning a second language seems to increase cognitive abilities.

- 3720 reads