Recall for a moment a situation in which you have experienced an intense emotional response. Perhaps you woke up in the middle of the night in a panic because you heard a noise that made you think that someone had broken into your house or apartment. Or maybe you were calmly cruising down a street in your neighborhood when another car suddenly pulled out in front of you, forcing you to slam on your brakes to avoid an accident. I’m sure that you remember that your emotional reaction was in large part physical. Perhaps you remember being flushed, your heart pounding, feeling sick to your stomach, or having trouble breathing. You were experiencing the physiological part of emotion—arousal—and I’m sure you have had similar feelings in other situations, perhaps when you were in love, angry, embarrassed, frustrated, or very sad.

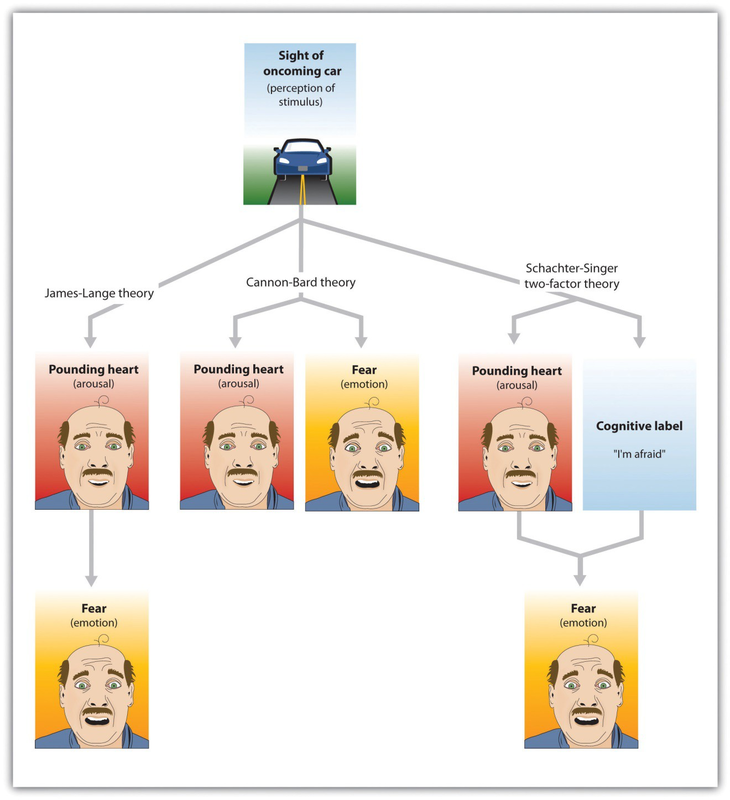

If you think back to a strong emotional experience, you might wonder about the order of the events that occurred. Certainly you experienced arousal, but did the arousal come before, after, or along with the experience of the emotion? Psychologists have proposed three different theories of emotion, which differ in terms of the hypothesized role of arousal in emotion (Figure 10.3).

If your experiences are like mine, as you reflected on the arousal that you have experienced in strong emotional situations, you probably thought something like, “I was afraid and my heart started beating like crazy.” At least some psychologists agree with this interpretation. According to the theory of emotion proposed by Walter Cannon and Philip Bard, the experience of the emotion (in this case, “I’m afraid”) occurs alongside our experience of the arousal (“my heart is beating fast”). According to the Cannon-Bard theory of emotion, the experienceof an emotion is accompanied byphysiological arousal. Thus, according to this model of emotion, as we become aware of danger, our heart rate also increases.

Although the idea that the experience of an emotion occurs alongside the accompanying arousal seems intuitive to our everyday experiences, the psychologists William James and Carl Lange had another idea about the role of arousal. According to the James-Lange theory of emotion, our experienceof an emotionis theresult of thearousal that we experience. This approach proposes that the arousal and the emotion are not independent, but rather that the emotion depends on the arousal. The fear does not occur along with the racing heart but occurs becauseof the racing heart. As William James put it, “We feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble” (James, 1884, p. 190). 1 A fundamental aspect of the James-Lange theory is that different patterns of arousal may create different emotional experiences.

There is research evidence to support each of these theories. The operation of the fa st emotional pathway (Figure 10.2) supports the idea that arousal and emotions occur together. The emotional circuits in the limbic system are activated when an emotional stimulus is experienced, and these circuits quickly create corresponding physical reactions (LeDoux, 2000). 2 The process happens so quickly that it may feel to us as if emotion is simultaneous with our physical arousal.

On the other hand, and as predicted by the James-Lange theory, our experiences of emotion are weaker without arousal. Patients who have spinal injuries that reduce their experience of arousal also report decreases in emotional responses (Hohmann, 1966). 3 There is also at least some support for the idea that different emotions are produced by different patterns of arousal. People who view fearful faces show more amygdala activation than those who watch angry or joyful faces (Whalen et al., 2001; Witvliet & Vrana, 1995), 4 we experience a red face and flushing when we are embarrassed but not when we experience other e motions (Leary, Britt, Cutlip, & Templeton, 1992), 5 and different hormones are released when we experience compassion than when we experience other e motions (Oatley, Keltner, & Jenkins, 2006). 6

The Two-Factor Theory of Emotion

Whereas the James-Lange theory proposes that each emotion has a different pattern of arousal, the two-factor theoryof emotion takes the opposite approach, arguing that the arousal that we experience is basically the same in every emotion, and that all emotions (including the basic emotions) are differentiated only by our cognitive appraisal of the source of the arousal. The two-factor theory of emotion asserts that the experienceof emotion is determined bytheintensity of thearousal weare experiencing, but that the cognitiveappraisal of thesituation determines what the emotion will be. Because both arousal and appraisal are necessary, we ca n say that emotions have two factors: an arousal factor and a cognitive factor (Schachter & Singer, 1962): 7

emotion = arousal + cognition

In some cases it may be difficult for a person who is experiencing a high level of arousal to accurately determine which emotion she is experiencing. That is, she may be certain that she is feeling arousal, but the meaning of the arousal (the cognitive factor) may be less clear. Some romantic relationships, for instance, have a very high level of arousal, and the partners alternatively experience extreme highs and lows in the relationship. One day they are madly in love with each other and the next they are in a huge fight. In situations that are accompanied by high arousal, people may be unsure what emotion they are experiencing. In the high arousal relationship, for instance, the partners may be uncertain whether the emotion they are feeling is love, hate, or both at the same time ( sound familiar?). Thetendencyfor peopleto incorrectly label thesourceof thearousal that theyare experiencing is known as the misattribution of arousal.

In one interesting field study by Dutton and Aron (1974), 8 an attractive young woman approached individual young men as they crossed a wobbly, long suspension walkway hanging more than 200 feet above a river in British Columbia, Canada. The woman asked each man to help her fill out a class questionnaire. When he had finished, she wrote her name and phone number on a piece of paper, and invited him to call if he wanted to hear more about the project. More than half of the men who had been interviewed on the bridge later called the woman. In contrast, men approached by the same woman on a low solid bridge, or who were interviewed on the suspension bridge by men, called significantly less frequently. The idea of misattribution of arousal can explain this result—the men were feeling arousal from the height of the bridge, but they misattributed it as romantic or sexual attraction to the woman, making them more likely to call her.

Research Focus: Misattributing Arousal

If you think a bit about your own experiences of different emotions, and if you consider the equation that suggests that emotions are represented by both arousal and cognition, you might start to wonder how much was determined by each. That is, do we know what emotion we are experiencing by monitoring our feelings (arousal) or by monitoring our thoughts (cognition)? The bridge study you just read about might begin to provide you an answer: The men seemed to be more influenced by their perceptions of how they should be feeling (their cognition) rather than by how they actually were feeling (their arousal).

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) 9 directly tested this prediction of the two-factor theory of emotion in a well-known experiment. Schachter and Singer believed that the cognitive part of the emotion was critical—in fact, they believed that the arousal that we are experiencing could be interpreted as any emotion, provided we had the right abel for it. Thus they hypothesized that if an individual is experiencing arousal for which he has no immediate explanation, he will “label” this state in terms of the cognitions that are created in his environment. On the other hand, they argued that people who already have a clear label for their arousal would have no need to search for a relevant label, and therefore should not experience an emotion.

In the research, male participants were told that they would be participating in a study on the effects of a new drug, called “suproxin,” on vision. On the basis of this cover story, the men were injected with a shot of the neurotransmitter epinephrine, a drug that normally creates feelings of tremors, flushing, and accelerated breathing in people. The idea was to give all the participants the experience of arousal.

Then, according to random assignment to conditions, the men were told that the drug would make them feel certain ways. The men in the epinephrine informed condition were told the truth about the effects of the drug—they were told that they would likely experience tremors, their hands would start to shake, their hearts would start to pound, and their faces might get warm and flushed. The participants in the epinephrine-uninformed condition, however, were told something untrue—that their feet would feel numb, that they would have an itching sensation over parts of their body, and that they might get a slight headache. The idea was to make some of the men think that the arousal they were experiencing was caused by the drug (the informedcondition), whereas others would be unsure where the arousal came from (the uninformedcondition).

Then the men were left alone with a confederate who they thought had received the same injection. While they were waiting for the experiment (which was supposedly about vision) to begin, the confederate behaved in a wild and crazy (Schachter and Singer called it “euphoric”) manner. He wadded up spitballs, flew paper airplanes, and played with a hula-hoop. He kept trying to get the participant to join in with his games. Then right before the vision experiment was to begin, the participants were asked to indicate their current emotional states on a number of scales. One of the emotions they were asked about was euphoria.

If you are following the story, you will realize what was expected: The men who had a label for their arousal (the informedgroup) would not be experiencing much emotion because they already had a label available for their arousal. The men in the misinformedgroup, on the other hand, were expected to be unsure about the source of the arousal. They needed to find an explanation for their arousal, and the confederate provided one. As you can see in Figure 10.4 (left side), this is just what they found. The participants in the misinformed condition were more likely to be experiencing euphoria (as measured by their behavioral responses with the confederate) than were those in the informed condition.

Then Schachter and Singer conducted another part of the study, using new participants. Everything was exactly the same except for the behavior of the confederate. Rather than being euphoric, he acted angry. He complained about having to complete the questionnaire he had been asked to do, indicating that the questions were stupid and too personal. He ended up tearing up the questionnaire that he was working on, yelling “I don’t have to tell them that!” Then he grabbed his books and stormed out of the room.

What do you think happened in this condition? The answer is the same thing: The misinformed participants experienced more anger (again as measured by the participant’s behaviors during the waiting period) than did the informed participants. (Figure 10.4, right side) The idea is that because cognitions are such strong determinants of emotional states, the same state of physiological arousal could be labeled in many different ways, depending entirely on the label provided by the social situation. As Schachter and Singer put it: “Given a state of physiological arousal for which an individual has no immediate explanation, he will ‘label’ this state and describe his feelings in terms of the cognitions available to him” (Schachter & Singer, 1962, p. 381). 10

Because it assumes that arousal is constant across emotions, the two-factor theory also predicts that emotions may transfer or “spill over” from one highly arousing event to another. My university basketball team recently won the NCAA basketball championship, but after the final victory some students rioted in the streets near the campus, lighting fires and burning cars. This seems to be a very strange reaction to such a positive outcome for the university and the students, but it can be explained through the spillover of the arousal caused by happiness to destructive behaviors. The principle of excitation transfer refers to the phenomenon that occurs when people who are already experiencing arousal from one event tend to also experience unrelated emotions more strongly.

In sum, each of the three theories of emotion has something to support it. In terms of Cannon-Bard, emotions and arousal generally are subjectively experienced together, and the spread is very fast. In support of the James-Lange theory, there is at least some evidence that arousal is necessary for the experience of e motion, and that the patterns of arousal are different for different emotions. And in line with the two-factor model, there is also evidence that we may interpret the same patterns of arousal differently in different situations.

- 94105 reads