Suretyship is the second of the three major types of consensual security arrangements noted at the beginning of this chapter (personal property security, suretyship, real property security)—and a common one. Creditors frequently ask the owners of small, closely held companies to guarantee their loans to the company, and parent corporations also frequently are guarantors of their subsidiaries’ debts. The earliest sureties were friends or relatives of the principal debtor who agreed—for free—to lend their guarantee. Today most sureties in commercial transaction are insurance companies (but insurance is not the same as suretyship).

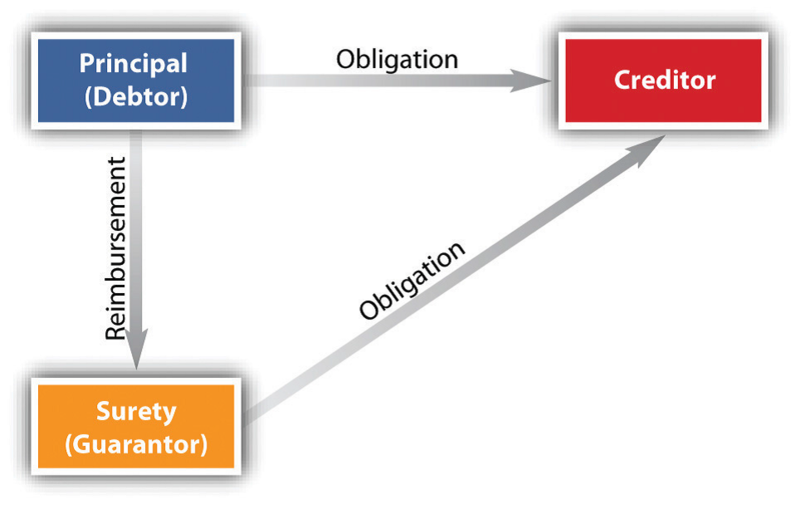

A surety is one who promises to pay or perform an obligation owed by theprincipal debtor, and, strictly speaking, the surety is primarily liable on the debt: the creditor can demand payment from the surety when the debt is due. The creditor is the person to whom the principal debtor (and the surety, strictly speaking) owes an obligation. Very frequently, the creditor requires first that the debtor put up collateral to secure indebtedness, and—in addition—that the debtor engage a surety to make extra certain the creditor is paid or performance is made. For example, David Debtor wants Bank to loan his corporation, David Debtor, Inc., $100,000. Bank says, “Okay, Mr. Debtor, we’ll loan the corporation money, but we want its computer equipment as security, and we want you personally to guarantee the debt if the corporation can’t pay.” Sometimes, though, the surety and the principal debtor may have no agreement between each other; the surety might have struck a deal with the creditor to act as surety without the consent or knowledge of the principal debtor.

A guarantor also is one who guarantees an obligation of another, and for practical purposes, therefore, guarantor is usually synonymous with surety—the terms are used pretty much interchangeably. But here’s the technical difference: a surety is usually a party to the original contract and signs her (or his, or its) name to the original agreement along with the surety; the consideration for the principal’s contract is the same as the surety’s consideration—she is bound on the contract from the very start, and she is also expected to know of the principal debtor’s default so that the creditor’s failure to inform her of it does not discharge her of any liability. On the other hand, a guarantor usually does not make his agreement with the creditor at the same time the principal debtor does: it’s a separate contract requiring separate consideration, and if the guarantor is not informed of the principal debtor’s default, the guarantor can claim discharge on the obligation to the extent any failure to inform him prejudices him. But, again, as the terms are mostly synonymous, surety is used here to encompass both.

- 2397 reads