A good part of both cognition and social cognition is spontaneous or automatic. Automatic cognition refers to thinking that occurs out of our awareness, quickly, and without taking much effort (Ferguson & Bargh, 2003; Ferguson, Hassin, & Bargh, 2008). The things that we do most frequently tend to become more automatic each time we do them, until they reach a level where they don’t really require us to think about them very much. Most of us can ride a bike and operate a television remote control in an automatic way. Even though it took some work to do these things when we were first learning them, it just doesn’t take much effort anymore. And because we spend a lot of time making judgments about others, many of these judgments, which are strongly influenced by our schemas, are made quickly and automatically (Willis & Todorov, 2006).

Because automatic thinking occurs outside of our conscious awareness, we frequently have no idea that it is occurring and influencing our judgments or behaviors. You might remember a time when you returned home, unlocked the door, and 30 seconds later couldn’t remember where you had put your keys! You know that you must have used the keys to get in, and you know you must have put them somewhere, but you simply don’t remember a thing about it. Because many of our everyday judgments and behaviors are performed automatically, we may not always be aware that they are occurring or influencing us.

It is of course a good thing that many things operate automatically because it would be extremely difficult to have to think about them all the time. If you couldn’t drive a car automatically, you wouldn’t be able to talk to the other people riding with you or listen to the radio at the same time—you’d have to be putting most of your attention into driving. On the other hand, relying on our snap judgments about Bianca—that she’s likely to be expressive, for instance—can be erroneous. Sometimes we need to—and should—go beyond automatic cognition and consider people more carefully. When we deliberately size up and think about something, for instance, another person, we call it controlled cognition. Although you might think that controlled cognition would be more common and that automatic thinking would be less likely, that is not always the case. The problem is that thinking takes effort and time, and we often don’t have too much of those things available.

In the following Research Focus, we consider an example of automatic cognition in a study that uses a common social cognitive procedure known as priming, a technique in which information is temporarily brought into memory through exposure to situational events, which can then influence judgments entirely out of awareness.

Research Focus: Behavioral Effects of Priming

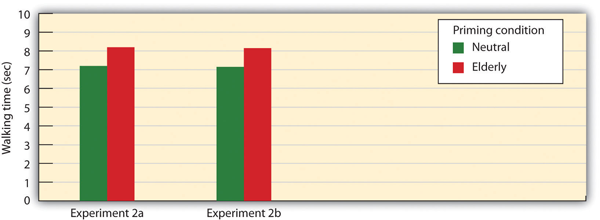

In one demonstration of how automatic cognition can influence our behaviors without us being aware of them, John Bargh and his colleagues (Bargh, Chen, & Burrows, 1996) conducted two studies, each with the exact same procedure. In the experiments, they showed college students sets of five scrambled words. The students were to unscramble the five words in each set to make a sentence. Furthermore, for half of the research participants, the words were related to the stereotype of elderly people. These participants saw words such as “in Florida retired live people” and “bingo man the forgetful plays.” The other half of the research participants also made sentences but did so out of words that had nothing to do with the elderly stereotype. The purpose of this task was to prime (activate) the schema of elderly people in memory for some of the participants but not for others. The experimenters then assessed whether the priming of elderly stereotypes would have any effect on the students’ behavior—and indeed it did. When each research participant had gathered all his or her belongings, thinking that the experiment was over, the experimenter thanked him or her for participating and gave directions to the closest elevator. Then, without the participant knowing it, the experimenters recorded the amount of time that the participant spent walking from the doorway of the experimental room toward the elevator. As you can see in Figure 2.10, the same results were found in both experiments—the participants who had made sentences using words related to the elderly stereotype took on the behaviors of the elderly—they walked significantly more slowly (in fact, about 12% more slowly across the two studies) as they left the experimental room.

To determine if these priming effects occurred out of the conscious awareness of the participants, Bargh and his colleagues asked a third group of students to complete the priming task and then to indicate whether they thought the words they had used to make the sentences had any relationship to each other or could possibly have influenced their behavior in any way. These students had no awareness of the possibility that the words might have been related to the elderly or could have influenced their behavior. The point of these experiments, and many others like them, is clear—it is quite possible that our judgments and behaviors are influenced by our social situations, and this influence may be entirely outside of our conscious awareness. To return again to Bianca, it is even possible that we notice her nationality and that our beliefs about Italians influence our responses to her, even though we have no idea that they are doing so and really believe that they have not.

- 16419 reads