Groups can make effective decisions only when they are able to make use of the advantages outlined above that come with group membership. However, these conditions are not always met in real groups. As we saw in the chapter opener, one example of a group process that can lead to very poor group decisions is groupthink. Groupthink occurs when a group that is made up of members who may actually be very competent and thus quite capable of making excellent decisions nevertheless ends up making a poor one as a result of a flawed group process and strong conformity pressures (Baron, 2005; Janis, 2007).

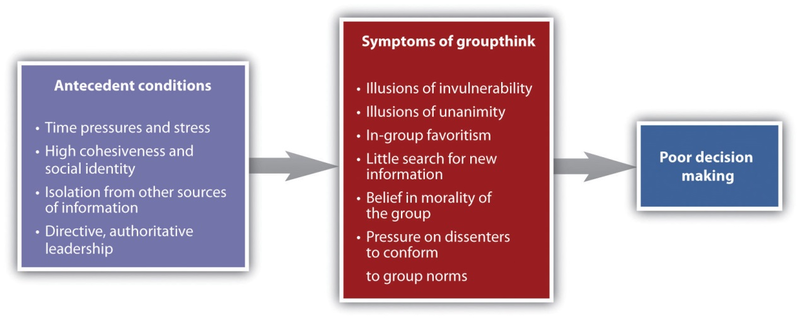

Groupthink is more likely to occur in groups in which the members are feeling strong social identity—for instance, when there is a powerful and directive leader who creates a positive group feeling, and in times of stress and crisis when the group needs to rise to the occasion and make an important decision. The problem is that groups suffering from groupthink become unwilling to seek out or discuss discrepant or unsettling information about the topic at hand, and the group members do not express contradictory opinions. Because the group members are afraid to express ideas that contradict those of the leader or to bring in outsiders who have other information, the group is prevented from making a fully informed decision. Figure 10.10 summarizes the basic causes and outcomes of groupthink.

Although at least some scholars are skeptical of the importance of groupthink in real group decisions (Kramer, 1998), many others have suggested that groupthink was involved in a number of well-known and important, but very poor, decisions made by government and business groups. Key historical decisions analyzed in terms of groupthink include the decision to invade Iraq made by President George Bush and his advisors, with the support of other national governments, including those from the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, and Australia; the decision of President John F. Kennedy and his advisors to commit U.S. forces to help with an invasion of Cuba, with the goal of overthrowing Fidel Castro in 1962; and the policy of appeasement of Nazi Germany pursued by many European leaders in 1930s, in the lead-up to World War II. Groupthink has also been applied to some less well-known, but also important, domains of decision making, including pack journalism (Matusitz, & Breen, 2012). Intriguingly, groupthink has even been used to try to account for perceived anti-right-wing political biases of social psychologists (Redding, 2012).

Careful analyses of the decision-making process in the historical cases outlined above have documented the role of conformity pressures. In fact, the group process often seems to be arranged to maximize the amount of conformity rather than to foster free and open discussion. In the meetings of the Bay of Pigs advisory committee, for instance, President Kennedy sometimes demanded that the group members give a voice vote regarding their individual opinions before the group actually discussed the pros and cons of a new idea. The result of these conformity pressures is a general unwillingness to express ideas that do not match the group norm.

The pressures for conformity also lead to the situation in which only a few of the group members are actually involved in conversation, whereas the others do not express any opinions. Because little or no dissent is expressed in the group, the group members come to believe that they are in complete agreement. In some cases, the leader may even select individuals (known as mindguards) whose job it is to help quash dissent and to increase conformity to the leader’s opinions.

An outcome of the high levels of conformity found in these groups is that the group begins to see itself as extremely valuable and important, highly capable of making high-quality decisions, and invulnerable. In short, the group members develop extremely high levels of conformity and social identity. Although this social identity may have some positive outcomes in terms of a commitment to work toward group goals (and it certainly makes the group members feel good about themselves), it also tends to result in illusions of invulnerability, leading the group members to feel that they are superior and that they do not need to seek outside information. Such a situation is often conducive to poor decision making, which can result in tragic consequences.

Interestingly, the composition of the group itself can affect the likelihood of groupthink occurring. More diverse groups, for instance, can help to ensure that a wider range of views are available to the group in making their decision, which can reduce the risk of groupthink. Thinking back to our case study, the more homogeneous the group are in terms of internal characteristics such as beliefs, and external characteristics such as gender, the more at risk of groupthink they may become (Kroon, Van Kreveld, & Rabbie, 1992). Perhaps, then, mixed gender corporate boards are more successful partly because they are better able to avoid the dangerous phenomenon of groupthink.

- 5712 reads