You may recall that one common finding in social psychology is that people frequently do not realize the extent to which behavior is influenced by the social situation. Although this is particularly true for the behavior of others, in some cases it may apply to understanding our own behavior as well. This means that, at least in some cases, we may believe that we have chosen to engage in a behavior for personal reasons, even though external, situational factors have actually led us to it. Consider again the children who did not play with the forbidden toy in the Aronson and Carlsmith study, even though they were given only a mild reason for not doing so. Although these children were actually led to avoid the toy by the power of the situation (they certainly would have played with it if the experimenter hadn’t told them not to), they frequently concluded that the decision was a personal choice and ended up believing that the toy was not that fun after all. When the social situation actually causes our behavior, but we do not realize that the social situation was the cause, we call the phenomenon insufficient justification. Insufficient justification occurs when the threat or reward is actually sufficient to get the person to engage in or to avoid a behavior, but the threat or reward is insufficient to allow the person to conclude that the situation caused the behavior.

Although insufficient justification leads people to like something less because they (incorrectly) infer that they did not engage in a behavior due to internal reasons, it is also possible that the opposite may occur. People may in some cases come to like a task less when they perceive that they did engage in it for external reasons. Overjustification occurs when we view our behavior as caused by the situation, leading us to discount the extent to which our behavior was actually caused by our own interest in it (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999; Lepper & Greene, 1978).

Mark Lepper and his colleagues (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973) studied the overjustification phenomenon by leading some children to think that they engaged in an activity for a reward rather than because they simply enjoyed it. First, they placed some fun felt-tipped markers into the classroom of the children they were studying. The children loved the markers and played with them right away. Then, the markers were taken out of the classroom and the children were given a chance to play with the markers individually at an experimental session with the researcher. At the research session, the children were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups. One group of children (the expected reward condition) was told that if they played with the markers they would receive a good-drawing award. A second group (the unexpected reward condition) also played with the markers and got the award—but they were not told ahead of time that they would be receiving the award (it came as a surprise after the session). The third group (the no reward condition) played with the markers too but got no award.

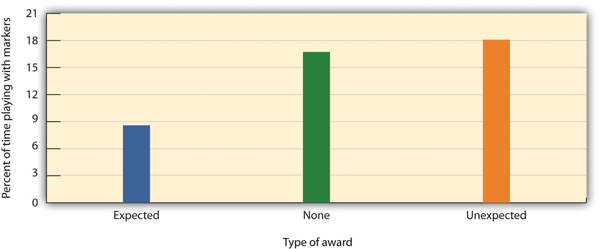

Then, the researchers placed the markers back in the classroom and observed how much the children in each of the three groups played with them. The results are shown in Figure 4.9. The fascinating result was that the children who had been led to expect a reward for playing with the markers during the experimental session played with the markers less at the second session than they had at the first session. Expecting to receive the award at the session had undermined their initial interest in the markers.

Although this might not seem logical at first, it is exactly what is expected on the basis of the principle of overjustification. When the children had to choose whether to play with the markers when the markers reappeared in the classroom, they based their decision on their own prior behavior. The children in the no reward condition group and the children in the unexpected reward condition group realized that they played with the markers because they liked them. Children in the expected award condition group, however, remembered that they were promised a reward for the activity before they played with the markers the last time. These children were more likely to infer that they play with the markers mostly for the external reward, and because they did not expect to get any reward for playing with the markers in the classroom, they discounted the possibility that they enjoyed playing the markers because they liked them. As a result, they played less frequently with the markers compared with the children in the other groups.

This research suggests that, although giving rewards may in many cases lead us to perform an activity more frequently or with more effort, reward may not always increase our liking for the activity. In some cases, reward may actually make us like an activity less than we did before we were rewarded for it. And this outcome is particularly likely when the reward is perceived as an obvious attempt on the part of others to get us to do something. When children are given money by their parents to get good grades in school, they may improve their school performance to gain the reward. But at the same time their liking for school may decrease. On the other hand, rewards that are seen as more internal to the activity, such as rewards that praise us, remind us of our achievements in the domain, and make us feel good about ourselves as a result of our accomplishments, are more likely to be effective in increasing not only the performance of, but also the liking of, the activity (Deci & Ryan, 2002; Hulleman, Durik, Schweigert, & Harackiewicz, 2008).

In short, when we use harsh punishments we may prevent a behavior from occurring. However, because the person sees that it is the punishment that is controlling the behavior, the person’s attitudes may not change. Parents who wish to encourage their children to share their toys or to practice the piano therefore would be wise to provide “just enough” external incentive. Perhaps a consistent reminder of the appropriateness of the activity would be enough to engage the activity, making a stronger reprimand or other punishment unnecessary. Similarly, when we use extremely positive rewards, we may increase the behavior but at the same time undermine the person’s interest in the activity.

The problem, of course, is finding the right balance between reinforcement and overreinforcement. If we want our child to avoid playing in the street, and if we provide harsh punishment for disobeying, we may prevent the behavior but not change the attitude. The child may not play in the street while we are watching but may do so when we leave. Providing less punishment is more likely to lead the child to actually change his or her beliefs about the appropriateness of the behavior, but the punishment must be enough to prevent the undesired behavior in the first place. The moral is clear: if we want someone to develop a strong attitude, we should use the smallest reward or punishment that is effective in producing the desired behavior.

- 12636 reads