Learning Objectives

- Describe some of the active and passive ways that conformity occurs in our everyday lives.

- Compare and contrast informational social influence and normative social influence.

- Summarize the variables that create majority and minority social influence.

- Outline the situational variables that influence the extent to which we conform.

The typical outcome of social influence is that our beliefs and behaviors become more similar to those of others around us. At times, this change occurs in a spontaneous and automatic sense, without any obvious intent of one person to change the other. Perhaps you learned to like jazz or rap music because your roommate was playing a lot of it. You didn’t really want to like the music, and your roommate didn’t force it on you—your preferences changed in passive way. Robert Cialdini and his colleagues (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990) found that college students were more likely to throw litter on the ground when they had just seen another person throw some paper on the ground and were least likely to litter when they had just seen another person pick up and throw paper into a trash can. The researchers interpreted this as a kind of spontaneous conformity—a tendency to follow the behavior of others, often entirely out of our awareness. Even our emotional states become more similar to those we spend more time with (Anderson, Keltner, & John, 2003).

Research Focus: Imitation as Subtle Conformity

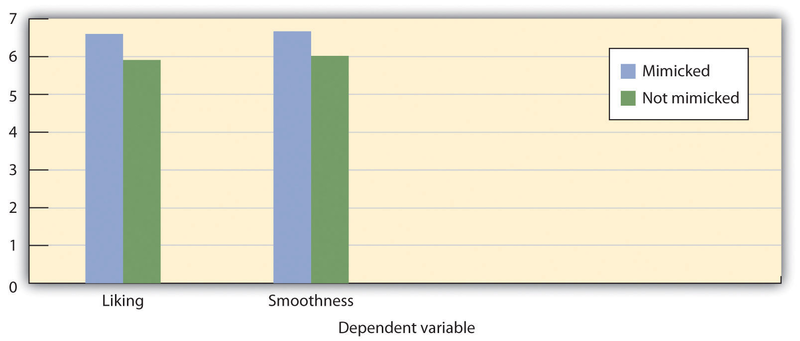

Perhaps you have noticed in your own behavior a type of very subtle conformity—the tendency to imitate other people who are around you. Have you ever found yourself talking, smiling, or frowning in the same way that a friend does? Tanya Chartrand and John Bargh (1999) investigated whether the tendency to imitate others would occur even for strangers, and even in very short periods of time. In their first experiment, students worked on a task with another student, who was actually an experimental confederate. The two worked together to discuss photographs taken from current magazines. While they were working together, the confederate engaged in some unusual behaviors to see if the research participant would mimic them. Specifically, the confederate either rubbed his or her face or shook his or her foot. It turned out that the students did mimic the behavior of the confederate, by themselves either rubbing their own faces or shaking their own feet. And when the experimenters asked the participants if they had noticed anything unusual about the behavior of the other person during the experiment, none of them indicated awareness of any face rubbing or foot shaking. It is said that imitation is a form of flattery, and we might therefore expect that we would like people who imitate us. Indeed, in a second experiment, Chartrand and Bargh found exactly this. Rather than creating the behavior to be mimicked, in this study the confederate imitated the behaviors of the participant. While the participant and the confederate discussed the magazine photos, the confederate mirrored the posture, movements, and mannerisms displayed by the participant. As you can see in Figure 6.2, the participants who had been mimicked liked the other person more and indicated that they thought the interaction had gone more smoothly, in comparison with the participants who had not been imitated.

Participants who had been mimicked indicated that they liked the person who had imitated them more and that the interaction with that person had gone more smoothly, in comparison with

participants who had not been mimicked. Data are from Chartrand and Bargh (1999).

Imitation is an important part of social interaction. We easily and frequently mimic others without being aware that we are doing so. We may communicate to others that we agree with their

viewpoints by mimicking their behaviors, and we tend to get along better with people with whom we are well “coordinated.” We even expect people to mimic us in social interactions, and we

become distressed when they do not (Dalton, Chartrand, & Finkel, 2010). This unconscious conformity may help explain why we hit it off immediately with some people and never get it

together with others (Chartrand & Dalton, 2009; Tickle-Degnen & Rosenthal, 1990, 1992).

- 4959 reads