As the number of people in the majority increases relative to the number of persons in the minority, pressure on the minority to conform also increases (Latané, 1981; Mullen, 1983). Asch conducted replications of his original line-judging study in which he varied the number of confederates (the majority subgroup members) who gave initial incorrect responses from one to 16 people, while holding the number in the minority subgroup constant at one (the single research participant). You may not be surprised to hear the results of this research: when the size of the majorities got bigger, the lone participant was more likely to give the incorrect answer.

Increases in the size of the majority increase conformity regardless of whether the conformity is informational or normative. In terms of informational conformity, if more people express an opinion, their opinions seem more valid. Thus bigger majorities should result in more informational conformity. But larger majorities will also produce more normative conformity because being different will be harder when the majority is bigger. As the majority gets bigger, the individual giving the different opinion becomes more aware of being different, and this produces a greater need to conform to the prevailing norm.

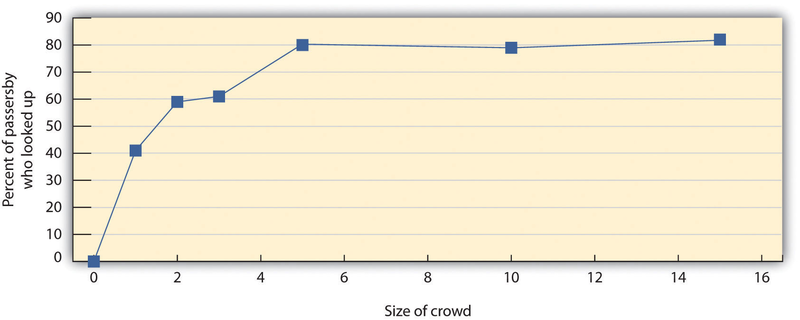

Although increasing the size of the majority does increase conformity, this is only true up to a point. The increase in the amount of conformity that is produced by adding new members to the majority group (known as the social impact of each group member) is greater for initial majority members than it is for later members (Latané, 1981). This pattern is shown in Figure 6.6, which presents data from a well-known experiment by Stanley Milgram and his colleagues (Milgram, Bickman, & Berkowitz, 1969) that studied how people are influenced by the behavior of others on the streets of New York City.

Milgram had confederates gather in groups on 42nd Street in New York City, in front of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, each looking up at a window on the sixth floor of the building. The confederates were formed into groups ranging from one to 15 people. A video camera in a room on the sixth floor above recorded the behavior of 1,424 pedestrians who passed along the sidewalk next to the groups.

As you can see in Figure 6.6 larger groups of confederates increased the number of people who also stopped and looked up, but the influence of each additional confederate was generally weaker as size increased. Groups of three confederates produced more conformity than did a single person, and groups of five produced more conformity than groups of three. But after the group reached about six people, it didn’t really matter very much. Just as turning on the first light in an initially dark room makes more difference in the brightness of the room than turning on the second, third, and fourth lights does, adding more people to the majority tends to produce diminishing returns—less additional effect on conformity.

One reason that the impact of new group members decreases so rapidly is because as the number in the group increases, the individuals in the majority are soon seen more as a group rather than as separate individuals. When there are only a couple of individuals expressing opinions, each person is likely to be seen as an individual, holding his or her own unique opinions, and each new individual adds to the impact. As a result, two people are more influential than one, and three more influential than two. However, as the number of individuals grows, and particularly when those individuals are perceived as being able to communicate with each other, the individuals are more likely to be seen as a group rather than as individuals. At this point, adding new members does not change the perception; regardless of whether there are four, five, six, or more members, the group is still just a group. As a result, the expressed opinions or behaviors of the group members no longer seem to reflect their own characteristics as much as they do that of the group as a whole, and thus increasing the number of group members is less effective in increasing influence (Wilder, 1977).

Group size is an important variable that influences a wide variety of behaviors of the individuals in groups. People leave proportionally smaller tips in restaurants as the number in their party increases, and people are less likely to help as the number of bystanders to an incident increases (Latané, 1981). The number of group members also has an important influence on group performance: as the size of a working group gets larger, the contributions of each individual member to the group effort become smaller. In each case, the influence of group size on behavior is found to be similar to that shown in Figure 6.6.

- 5026 reads