Even if we have noticed the emergency and interpret it as being one, this does not necessarily mean that we will come to the rescue of the other person. We still need to decide that it is our responsibility to do something. The problem is that when we see others around, it is easy to assume that they are going to do something and that we don’t need to do anything. Diffusion of responsibilityoccurs when we assume that others will take action and therefore we do not take action ourselves. The irony, of course, is that people are more likely to help when they are the only ones in the situation than they are when there are others around.

Darley and Latané (1968) had study participants work on a communication task in which they were sharing ideas about how to best adjust to college life with other people in different rooms using an intercom. According to random assignment to conditions, each participant believed that he or she was communicating with either one, two, or five other people, who were in either one, two, or five other rooms. Each participant had an initial chance to give his or her opinions over the intercom, and on the first round one of the other people (actually a confederate of the experimenter) indicated that he had an “epileptic-like” condition that had made the adjustment process very difficult for him. After a few minutes, the subject heard the experimental confederate say,

I-er-um-I think I-I need-er-if-if could-er-er-somebody er-er-er-er-er-er-er give me a liltle-er-give me a little help here because-er-I-er-I’m-er-er having a-a-a real problcm-er-right now and I-er-if somebody could help me out it would-it would-er-er s-s-sure be-sure be good…because there-er-er-a cause I-er-I-uh-I’ve got a-a one of the-er-sei er-er-things coming on and-and-and I could really-er-use some help so if somebody would-er-give me a little h-help-uh-er-er-er-er-er c-could somebody-er-er-help-er-uh-uh-uh (choking sounds).…I’m gonna die-er-er-I’m…gonna die-er-help-er-er-seizure-er- (chokes, then quiet). (Darley & Latané, 1968, p. 379)

As you can see in Figure 8.9, the participants who thought that they were the only ones who knew about the emergency (because they were only working with one other person) left the room quickly to try to get help. In the larger groups, however, participants were less likely to intervene and slower to respond when they did. Only 31% of the participants in the largest groups responded by the end of the six-minute session.

You can see that the social situation has a powerful influence on helping. We simply don’t help as much when other people are with us.

|

Group size |

Average helping (%) |

Average time to help (in seconds) |

|

2 (Participant and victim) |

85 |

52 |

|

3 (Participant, victim, and 1 other) |

62 |

93 |

|

6 (Participant, victim, and 4 others) |

31 |

166 |

|

*Source: Darley and Latané (1968). |

||

Perhaps you have noticed diffusion of responsibility if you have participated in an Internet users’ group where people asked questions of the other users. Did you find that it was easier to get help if you directed your request to a smaller set of users than when you directed it to a larger number of people? Consider the following: In 1998, Larry Froistad, a 29-year-old computer programmer, sent the following message to the members of an Internet self-help group that had about 200 members. “Amanda I murdered because her mother stood between us…when she was asleep, I got wickedly drunk, set the house on fire, went to bed, listened to her scream twice, climbed out the window and set about putting on a show of shock and surprise.” Despite this clear online confession to a murder, only 3 of the 200 newsgroup members reported the confession to the authorities (Markey, 2000).

To study the possibility that this lack of response was due to the presence of others, the researchers (Markey, 2000) conducted a field study in which they observed about 5,000 participants in about 400 different chat groups. The experimenters sent a message to the group, from either a male or female screen name (JakeHarmen or SuzyHarmen). Help was sought by either asking all the participants in the chat group, “Can anyone tell me how to look at someone’s profile?” or by randomly selecting one participant and asking “[name of selected participant], can you tell me how to look at someone’s profile?” The experimenters recorded the number of people present in the chat room, which ranged from 2 to 19, and then waited to see how long it took before a response was given.

It turned out that the gender of the person requesting help made no difference, but that addressing to a single person did. Assistance was received more quickly when help was asked for by specifying a participant’s name (in only about 37 seconds) than when no name was specified (51 seconds). Furthermore, a correlational analysis found that when help was requested without specifying a participant’s name, there was a significant negative correlation between the number of people currently logged on in the group and the time it took to respond to the request.

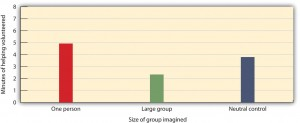

Garcia, Weaver, Moskowitz, and Darley (2002) found that the presence of others can promote diffusion of responsibility even if those other people are only imagined. In these studies, the researchers had participants read one of three possible scenarios that manipulated whether participants thought about dining out with 10 friends at a restaurant (group condition) or whether they thought about dining at a restaurant with only one other friend (one-person condition). Participants in the group condition were asked to “Imagine you won a dinner for yourself and 10 of your friends at your favorite restaurant.” Participants in the one-person condition were asked to “Imagine you won a dinner for yourself and a friend at your favorite restaurant.”

After reading one of the scenarios, the participants were then asked to help with another experiment supposedly being conducted in another room. Specifically, they were asked: “How much time are you willing to spend on this other experiment?” At this point, participants checked off one of the following minute intervals: 0 minutes, 2 minutes, 5 minutes, 10 minutes, 15 minutes, 20 minutes, 25 minutes, and 30 minutes.

Garcia et al. (2002) found that the presence of others reduced helping, even when those others were only imagined.

As you can see in Figure 8.9, simply imagining that they were in a group or alone had a significant effect on helping, such that those who imagined being with only one other person volunteered to help for more minutes than did those who imagined being in a larger group.

- 2738 reads