Although thinking about others in terms of their social category memberships has some potential benefits for the person who does the categorizing, categorizing others, rather than treating them as unique individuals with their own unique characteristics, has a wide variety of negative, and often very unfair, outcomes for those who are categorized.

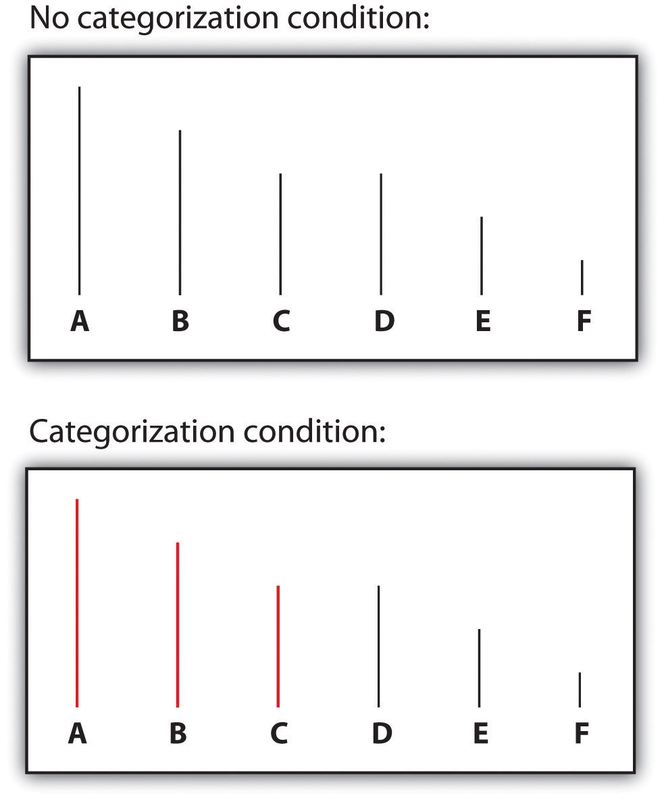

One problem is that social categorization distorts our perceptions such that we tend to exaggerate the differences between people from different social groups while at the same time perceiving members of groups (and particularly outgroups) as more similar to each other than they actually are. This overgeneralization makes it more likely that we will think about and treat all members of a group the same way. Tajfel and Wilkes (1963) performed a simple experiment that provided a picture of the potential outcomes of categorization. As you can see in Figure 11.5, the experiment involved having research participants judge the length of six lines. In one of the experimental conditions, participants simply saw six lines, whereas in the other condition, the lines were systematically categorized into two groups—one comprising the three shorter lines and one comprising the three longer lines.

Tajfel found that the lines were perceived differently when they were categorized, such that the differences between the groups and the similarities within the groups were emphasized. Specifically, he found that although lines C and D (which are actually the same length) were perceived as equal in length when the lines were not categorized, line D was perceived as being significantly longer than line C in the condition in which the lines were categorized. In this case, categorization into two groups—the “short lines group” and the “long lines group”—produced a perceptual bias such that the two groups of lines were seen as more different than they really were.

Similar effects occur when we categorize other people. We tend to see people who belong to the same social group as more similar than they actually are, and we tend to judge people from different social groups as more different than they actually are. The tendency to see members of social groups as similar to each other is particularly strong for members of outgroups, resulting in outgroup homogeneity—the tendency to view members of outgroups as more similar to each other than we see members of ingroups (Linville, Salovey, & Fischer, 1986; Ostrom & Sedikides, 1992; Meissner & Brigham, 2001). Perhaps you have had this experience yourself when you found yourself thinking or saying, “Oh, them, they’re all the same!”

Patricia Linville and Edward Jones (1980) gave research participants a list of trait terms and asked them to think about either members of their own group (e.g., Blacks) or members of another group (e.g., Whites) and to place the trait terms into piles that represented different types of people in the group. The results of these studies, as well as other studies like them, were clear: people perceive outgroups as more homogeneous than their ingroup. Just as White people used fewer piles of traits to describe Blacks than Whites, young people used fewer piles of traits to describe elderly people than they did young people, and students used fewer piles for members of other universities than they did for members of their own university.

Outgroup homogeneity occurs in part because we don’t have as much contact with outgroup members as we do with ingroup members, and the quality of interaction with outgroup members is often more superficial. This prevents us from really learning about the outgroup members as individuals, and as a result, we tend to be unaware of the differences among the group members. In addition to learning less about them because we see and interact with them less, we routinely categorize outgroup members, thus making them appear more cognitively similar (Haslam, Oakes, & Turner, 1996).

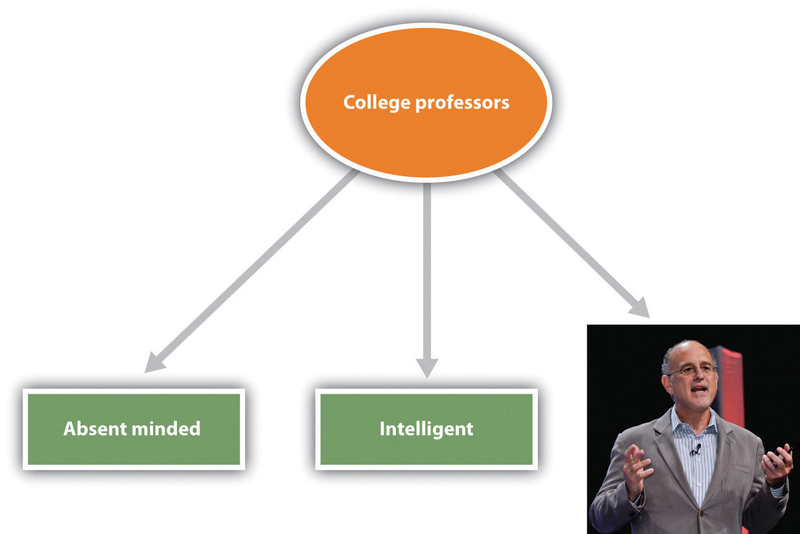

Once we begin to see the members of outgroups as more similar to each other than they actually are, it then becomes very easy to apply our stereotypes to the members of the groups without having to consider whether the characteristic is actually true of the particular individual. If men think that women are all alike, then they may also think that they all have the same positive and negative characteristics (e.g., they’re nurturing, emotional). And women may have similarly simplified beliefs about men (e.g., they’re strong, unwilling to commit). The outcome is that the stereotypes become linked to the group itself in a set of mental representations (Figure 11.6). The stereotypes are “pictures in our heads” of the social groups (Lippman, 1922). These beliefs just seem right and natural, even though they are frequently distorted overgeneralizations (Hirschfeld, 1996; Yzerbyt, Schadron, Leyens, & Rocher, 1994).

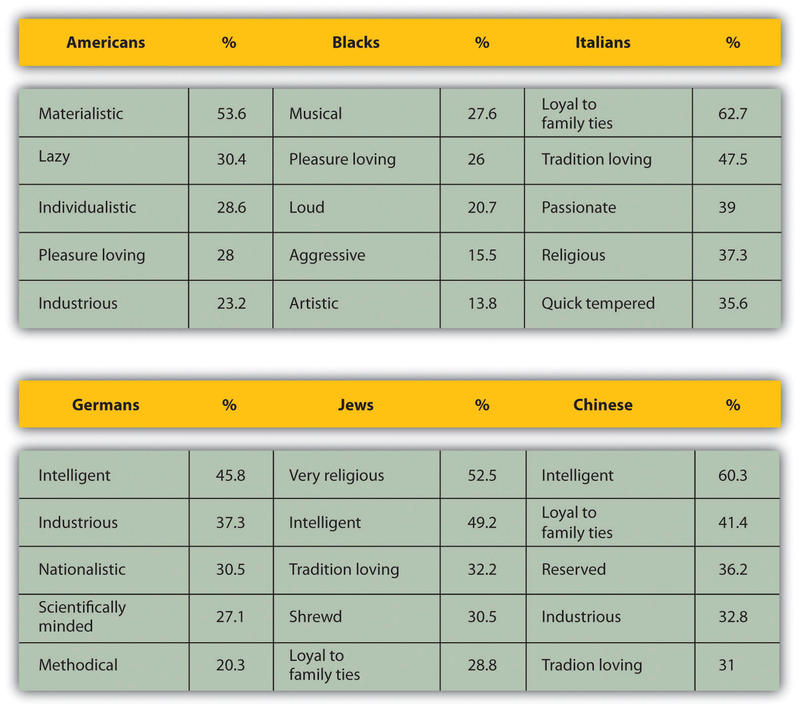

Our stereotypes and prejudices are learned through many different processes. This multiplicity of causes is unfortunate because it makes stereotypes and prejudices even more likely to form and harder to change. For one, we learn our stereotypes in part through our communications with parents and peers (Aboud & Doyle, 1996) and from the behaviors we see portrayed in the media (Brown, 1995). Even five-year-old children have learned cultural norms about the appropriate activities and behaviors for boys and girls and also have developed stereotypes about age, race, and physical attractiveness (Bigler & Liben, 2006). And there is often good agreement about the stereotypes of social categories among the individuals within a given culture. In one study assessing stereotypes, Stephanie Madon and her colleagues (Madon et al., 2001) presented U.S. college students with a list of 84 trait terms and asked them to indicate for which groups each trait seemed appropriate (***Figure 11.7, “Current Stereotypes Held by College Students”***). The participants tended to agree about what traits were true of which groups, and this was true even for groups of which the respondents were likely to never have met a single member (Arabs and Russians). Even today, there is good agreement about the stereotypes of members of many social groups, including men and women and a variety of ethnic groups.

Once they become established, stereotypes (like any other cognitive representation) tend to persevere. We begin to respond to members of stereotyped categories as if we already knew what they were like. Yaacov Trope and Eric Thompson (1997) found that individuals addressed fewer questions to members of categories about which they had strong stereotypes (as if they already knew what these people were like) and that the questions they did ask were likely to confirm the stereotypes they already had.

In other cases, stereotypes are maintained because information that confirms our stereotypes is better remembered than information that disconfirms them. When we see members of social groups perform behaviors, we tend to better remember information that confirms our stereotypes than we remember information that disconfirms our stereotypes (Fyock & Stangor, 1994). If we believe that women are bad drivers and we see a woman driving poorly, then we tend to remember it, but when we see a woman who drives particularly well, we tend to forget it. This illusory correlation is another example of the general principle of assimilation—we tend to perceive the world in ways that make it fit our existing beliefs more easily than we change our beliefs to fit the reality around us.

And stereotypes become difficult to change because they are so important to us—they become an integral and important part of our everyday lives in our culture. Stereotypes are frequently expressed on TV, in movies, and in social media, and we learn a lot of our beliefs from these sources. Our friends also tend to hold beliefs similar to ours, and we talk about these beliefs when we get together with them (Schaller & Conway, 1999). In short, stereotypes and prejudice are powerful largely because they are important social norms that are part of our culture (Guimond, 2000).

Because they are so highly cognitively accessible, and because they seem so “right,” our stereotypes easily influence our judgments of and responses to those we have categorized. The social psychologist John Bargh once described stereotypes as “cognitive monsters” because their activation was so powerful and because the activated beliefs had such insidious influences on social judgment (Bargh, 1999). Making things even more difficult, stereotypes are strongest for the people who are in most need of change—the people who are most prejudiced (Lepore & Brown, 1997).

Because stereotypes and prejudice often operate out of our awareness, and also because people are frequently unwilling to admit that they hold them, social psychologists have developed methods for assessing them indirectly. In the Research Focus box following, we will consider two of these approaches—the bogus pipeline procedure and the Implicit Association Test (IAT).

Research Focus: Measuring Stereotypes Indirectly

One difficulty in measuring stereotypes and prejudice is that people may not tell the truth about their beliefs. Most people do not want to admit—either to themselves or to others—that they

hold stereotypes or that they are prejudiced toward some social groups. To get around this problem, social psychologists make use of a number of techniques that help them measure these

beliefs more subtly and indirectly. One indirect approach to assessing prejudice is called the bogus pipeline procedure (Jones & Sigall, 1971). In this procedure, the experimenter first

convinces the participants that he or she has access to their “true” beliefs, for instance, by getting access to a questionnaire that they completed at a prior experimental session. Once the

participants are convinced that the researcher is able to assess their “true” attitudes, it is expected that they will be more honest in answering the rest of the questions they are asked

because they want to be sure that the researcher does not catch them lying.

Interestingly, people express more prejudice when they are in the bogus pipeline than they do when they are asked the same questions more directly, which suggests that we may frequently mask

our negative beliefs in public. Other indirect measures of prejudice are also frequently used in social psychological research; for instance, assessing nonverbal behaviors such as speech

errors or physical closeness. One common measure involves asking participants to take a seat on a chair near a person from a different racial or ethnic group and measuring how far away the

person sits (Sechrist & Stangor, 2001; Word, Zanna, & Cooper, 1974). People who sit farther away are assumed to be more prejudiced toward the members of the group.

Because our stereotypes are activated spontaneously when we think about members of different social groups, it is possible to use reaction-time measures to assess this activation and thus to

learn about people’s stereotypes and prejudices. In these procedures, participants are asked to make a series of judgments about pictures or descriptions of social groups and then to answer

questions as quickly as they can, but without making mistakes. The speed of these responses is used to determine an individual’s stereotypes or prejudice.

The most popular reaction-time implicit measure of prejudice—the Implicit Association Test (IAT)—is frequently used to assess stereotypes and prejudice (Nosek, Greenwald, & Banaji, 2007).

In the IAT, participants are asked to classify stimuli that they view on a computer screen into one of two categories by pressing one of two computer keys, one with their left hand and one

with their right hand. Furthermore, the categories are arranged so that the responses to be answered with the left and right buttons either “fit with” (match) the stereotype or do not “fit

with” (mismatch) the stereotype. For instance, in one version of the IAT, participants are shown pictures of men and women and are also shown words related to academic disciplines (e.g.,

History, French, or Linguistics for the Arts, or Chemistry, Physics, or Math for the Sciences). Then the participants categorize the photos (“Is this picture a picture of a man or a woman?”)

and answer questions about the disciplines (“Is this discipline a science?) by pressing either the Yes button or the No button using either their left hand or their right hand. When the

responses are arranged on the screen in a way that matches a stereotype, such that the male category and the “science” category are on the same side of the screen (e.g., on the right side),

participants can do the task very quickly and they make few mistakes. It’s just easier, because the stereotypes are matched or associated with the pictures in a way that makes sense or is

familiar. But when the images are arranged such that the female category and the “science” category are on the same side, whereas the men and the weak categories are on the other side, most

participants make more errors and respond more slowly. The basic assumption is that if two concepts are associated or linked, they will be responded to more quickly if they are classified

using the same, rather than different, keys. Implicit association procedures such as the IAT show that even participants who claim that they are not prejudiced do seem to hold cultural

stereotypes about social groups. Even Black people themselves respond more quickly to positive words that are associated with White rather than Black faces on the IAT, suggesting that they

have subtle racial prejudice toward their own racial group. Because they hold these beliefs, it is possible—although not guaranteed—that they may use them when responding to other people,

creating a subtle and unconscious type of discrimination. Although the meaning of the IAT has been debated (Tetlock & Mitchell, 2008), research using implicit measures does suggest

that—whether we know it or not, and even though we may try to control them when we can—our stereotypes and prejudices are easily activated when we see members of different social categories

(Barden, Maddux, Petty, & Brewer, 2004). Do you hold implicit prejudices? Try the IAT yourself here.

Although in some cases the stereotypes that are used to make judgments might actually be true of the individual being judged, in many other cases they are not. Stereotyping is problematic when the stereotypes we hold about a social group are inaccurate overall, and particularly when they do not apply to the individual who is being judged (Stangor, 1995). Stereotyping others is simply unfair. Even if many women are more emotional than are most men, not all are, and it is not right to judge any one woman as if she is.

In the end, stereotypes become self-fulfilling prophecies, such that our expectations about the group members make the stereotypes come true (Snyder, Tanke, & Berscheid, 1977; Word, Zanna, & Cooper, 1974). Once we believe that men make better leaders than women, we tend to behave toward men in ways that makes it easier for them to lead. And we behave toward women in ways that makes it more difficult for them to lead. The result? Men find it easier to excel in leadership positions, whereas women have to work hard to overcome the false beliefs about their lack of leadership abilities (Phelan & Rudman, 2010). This is likely why female lawyers with masculine names are more likely to become judges (Coffey & McLaughlin, 2009) and masculine-looking applicants are more likely to be hired as leaders than feminine-looking applicants (von Stockhausen, Koeser, & Sczesny, 2013).

These self-fulfilling prophecies are ubiquitous—even teachers’ expectations about their students’ academic abilities can influence the students’ school performance (Jussim, Robustelli, & Cain, 2009).

Of course, you may think that you personally do not behave in these ways, and you may not. But research has found that stereotypes are often used out of our awareness, which makes it very difficult for us to correct for them. Even when we think we are being completely fair, we may nevertheless be using our stereotypes to condone discrimination (Chen & Bargh, 1999). And when we are distracted or under time pressure, these tendencies become even more powerful (Stangor & Duan, 1991).

Furthermore, attempting to prevent our stereotype from coloring our reactions to others takes effort. We experience more negative affect (particularly anxiety) when we are with members of other groups than we do when we are with people from our own groups, and we need to use more cognitive resources to control our behavior because of our anxiety about revealing our stereotypes or prejudices (Butz & Plant, 2006; Richeson & Shelton, 2003). When we know that we need to control our expectations so that we do not unintentionally stereotype the other person, we may try to do so—but doing so takes effort and may frequently fail (Macrae, Bodenhausen, Milne, & Jetten, 1994).

- 16958 reads