The research on intergroup contact suggests that although contact may improve prejudice, it may make it worse if it is not implemented correctly. Improvement is likely only when the contact moves the members of the groups to feel that they are closer to each other rather than further away from each other. In short, groups are going to have better attitudes toward each other when they see themselves more similarly to each other—when they feel more like one large group than a set of smaller groups.

This fact was demonstrated in a very convincing way in what is now a classic social psychological study. In the “Robbers’ Cave Experiment,” Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood, and Sherif (1961) studied the group behavior of 11-year-old boys at a summer camp. Although the boys did not know it, the researchers carefully observed the behaviors of the children during the camp session, with the goal of learning about how group conflict developed and how it might be resolved among the children.

During the first week of the camp, the boys were divided into two groups that camped at two different campsites. During this time, friendly relationships developed among the boys within each of the two groups. Each group developed its own social norms and group structure and became quite cohesive, with a strong positive social identity. The two groups chose names for themselves (the Rattlers and the Eagles), and each made their own group flag and participated in separate camp activities.

At the end of this one-week baseline period, it was arranged that the two groups of boys would become aware of each other’s presence. Furthermore, the researchers worked to create conditions that led to increases in each group’s social identity and at the same time created negative perceptions of the other group. The researchers arranged baseball games, a tug-of-war, and a treasure hunt and offered prizes for the group that won the competitions. Almost immediately, this competition created ingroup favoritism and prejudice, and discrimination quickly followed. By the end of the second week, the Eagles had sneaked up to the Rattlers’ cabin and stolen their flag. When the Rattlers discovered the theft, they in turn raided the Eagles’ cabin, stealing things. There were food fights in the dining room, which was now shared by the groups, and the researchers documented a substantial increase in name-calling and stereotypes of the outgroup. Some fistfights even erupted between members of the different groups.

The researchers then intervened by trying to move the groups closer to each other. They began this third stage of the research by setting up a series of situations in which the boys had to work together to solve a problem. These situations were designed to create interdependence by presenting the boys with superordinate goals—goals that were both very important to them and yet that required the cooperative efforts and resources of both the Eagles and the Rattlers to attain. These goals involved such things as the need to pool money across both groups in order to rent a movie that all the campers wanted to view, or the need to pull together on ropes to get a food truck that had become stuck back onto the road. As the children worked together to meet these goals, the negative perceptions of the group members gradually improved; there was a reduction of hostility between the groups and an emergence of more positive intergroup attitudes.

This strategy was effective because it led the campers to perceive both the ingroup and the outgroup as one large group (“we”) rather than as two separate groups (“us” and “them”). As differentiation between the ingroup and the outgroup decreases, so should ingroup favoritism, prejudice, and conflict. The differences between the original groups are still present, but they are potentially counteracted by perceived similarities in the second superordinate group. The attempt to reduce prejudice by creating a superordinate categorization is known as the goal of creating a common ingroup identity (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2008), and we can diagram the relationship as follows:

interdependence and cooperation → common ingroup identity → favorable intergroup attitudes.

A substantial amount of research has supported the predictions of the common ingroup identity model. For instance, Samuel Gaertner and his colleagues (Gaertner, Mann, Murrell, & Dovidio, 1989) tested the hypothesis that interdependent cooperation in groups reduces negative beliefs about outgroup members because it leads people to see the others as part of the ingroup (by creating a common identity). In this research, college students were brought to a laboratory where they were each assigned to one of two teams of three members each, and each team was given a chance to create its own unique group identity by working together. Then, the two teams were brought into a single room to work on a problem. In one condition, the two teams were told to work together as a larger, six-member team to solve the problem, whereas in the other condition, the two teams worked on the problem separately.

Consistent with the expected positive results of creating a common group identity, the interdependence created in the condition where the teams worked together increased the tendency of the team members to see themselves as members of a single larger team, and this in turn reduced the tendency for each group to show ingroup favoritism.

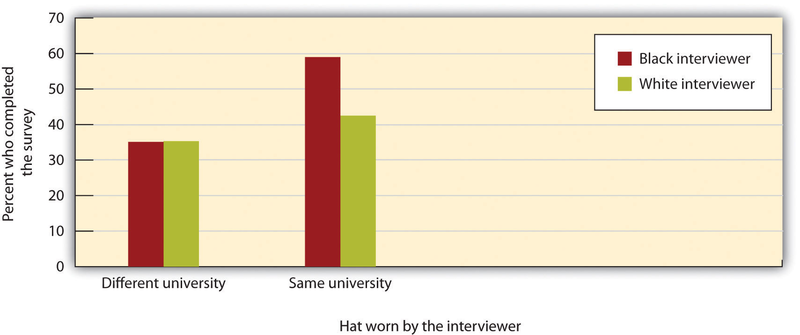

But the benefits of recategorization are not confined to laboratory settings—they also appear in our everyday interactions with other people. Jason Neir and his colleagues had Black and White interviewers approach White students who were attending a football game (Neir et al., 2001). The dependent measure was whether or not they agreed to help the interviewer by completing a questionnaire. However, the interviewers also wore hats representing either one of the two universities who were playing in the game. As you can see in Figure 11.11, the data were analyzed both by whether the interviewer and the student were of the same race (either both White or one White and one Black) and also by whether they wore hats from the same or different universities. As expected on the basis of recategorization and the common ingroup identity approach, the White students were significantly more likely to help the Black interviewers when they wore a hat of the same university as that worn by the interviewee. The hat evidently led the White students to recategorize the interviewer as part of the university ingroup, leading to more helping. However, whether the individuals shared university affiliation did not influence helping for the White participants, presumably because they already saw the interviewer as a member of the ingroup (the interviewer was also White).

In this field study, White and Black interviewers asked White students attending a football game to help them by completing a questionnaire. The data were analyzed both by whether the request was to a White (ingroup) or Black (outgroup) student and also by whether the individual whose help was sought wore the same hat that they did or a different hat. Results supported the common ingroup identity model. Helping was much greater for outgroup members when hats were the same. Data are from Neir et al. (2001).

Again, the implications of these results are clear and powerful. If we want to improve attitudes among people, we must get them to see each other as more similar and less different. And even relatively simple ways of doing so, such as wearing a hat that suggests an ingroup identification, can be successful.

Key Takeaways

- Changing our stereotypes and prejudices is not easy, and attempting to suppress them may backfire. However, with appropriate effort, we can reduce our tendency to rely on our stereotypes and prejudices.

- One approach to changing stereotypes and prejudice is by changing social norms—for instance, through education and laws enforcing equality.

- Prejudice will change faster when it is confronted by people who see it occurring. Confronting prejudice may be embarrassing, but it also can make us feel that we have done the right thing.

- Intergroup attitudes will be improved when we can lead people to focus more on their connections with others. Intergroup contact, extended contact with others who share friends with outgroup members, and a common ingroup identity are all examples of this process.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Visit the website and watch the program “A Class Divided.” Do you think Jane Elliott’s method of teaching people about prejudice is ethical?

- Have you ever confronted or failed to confront a person who you thought was expressing prejudice or discriminating? Why did you confront (or not confront) that person, and how did doing so make you feel?

- Imagine you are a teacher in a classroom and you see that some children expressing prejudice or discrimination toward other children on the basis of their race. What techniques would you use to attempt to reduce these negative behaviors?

References

Aronson, E. (2004). Reducing hostility and building compassion: Lessons from the jigsaw classroom. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (pp. 469–488). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Aronson, E., Blaney, N., Stephan, C., Sikes, J., & Snapp, M. (1978). The jig-saw classroom. London, England: Sage.

Blair, I. V. (2002). The malleability of automatic stereotypes and prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(3), 242–261.

Blair, I. V., Ma, J. E., & Lenton, A. P. (2001). Imagining stereotypes away: The moderation of implicit stereotypes through mental imagery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 828–841.

Bodenhausen, G. V., Schwarz, N., Bless, H., & Wanke, M. (1995). Effects of atypical exemplars on racial beliefs: Enlightened racism or generalized appraisals? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31, 48–63.

Brodt, S. E., & Ross, L. D. (1998). The role of stereotyping in overconfident social prediction. Social Cognition, 16, 225–252.

Czopp, A. M., Monteith, M. J., & Mark, A. Y. (2006). Standing up for a change: Reducing bias through interpersonal confrontation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 784–803.

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (Eds.). (2008). Addressing contemporary racism: The common ingroup identity model. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Gaertner, S. L., Mann, J., Murrell, A., & Dovidio, J. F. (1989). Reducing intergroup bias: The benefits of recategorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(2), 239–249.

Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 708–724.

Halpert, S. C. (2002). Suicidal behavior among gay male youth. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 6, 53–79.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1997). Strength of identification and intergroup differentiation: The influence of group norms. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(5), 603–609.

Kaiser, C. R., & Miller, C. T. (2001). Stop complaining! The social costs of making attributions to discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 254–263.

Kawakami, K., Dovidio, J. F., Moll, J., Hermsen, S., & Russin, A. (2000). Just say no (to stereotyping): Effects of training in the negation of stereotypic associations on stereotype activation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,78 (5), 871–888.

Klonoff, E. A., Landrine, H., & Campbell, R. (2000). Sexist discrimination may account for well-known gender differences in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 93–99.

Klonoff, E. A., Landrine, H., & Ullman, J. B. (1999). Racial discrimination and psychiatric symptoms among blacks. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 5(4), 329–339.

Macrae, C. N., Bodenhausen, G. V., Milne, A. B., & Jetten, J. (1994). Out of mind but back in sight: Stereotypes on the rebound. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 808–817.

Madon, S., Jussim, L., Keiper, S., Eccles, J., Smith, A., & Palumbo, P. (1998). The accuracy and power of sex, social class, and ethnic stereotypes: A naturalistic study in person perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12), 1304–1318.

Mallett, R. K., Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2008). Expect the unexpected: Failure to anticipate similarities leads to an intergroup forecasting error. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 265–277. doi: 10.1037/0022–3514.94.2.94.2.265

Neir, J. A., Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Banker, B. S., Ward, C. M., & Rust, C. R. (2001). Changing interracial evaluations and behavior: The effects of a common group identity. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 4, 299–316.

Neuberg, S. L., & Fiske, S. T. (1987). Motivational influences on impression formation: Outcome dependency, accuracy-driven attention, and individuating processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 431–444.

Oreopolous, P. (2011). Why do skilled immigrants struggle in the labor market? A field experiment with six thousand résumés. American Economic Journal, 3(4), 148-171.

Page-Gould, E., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). With a little help from my cross-group friend: Reducing anxiety in intergroup contexts through cross-group friendship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1080–1094. doi: 10.1037/0022–3514.95.5.1080.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783.

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2007). Negotiating interracial interactions: Costs, consequences, and possibilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 316–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1467–8721.2007.00528.x

Rothbart, M., & John, O. P. (1985). Social categorization and behavioral episodes: A cognitive analysis of the effects of intergroup contact. Journal of Social Issues, 41, 81–104.

Rudman, L. A., Ashmore, R. D., & Gary, M. L. (2001). “Unlearning” automatic biases: The malleability of implicit prejudice and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 856–868.

Sechrist, G., & Stangor, C. (2001). Perceived consensus influences intergroup behavior and stereotype accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(4), 645–654.

Shelton, J. N., Richeson, J. A., Salvatore, J., & Hill, D. M. (Eds.). (2006). Silence is not golden: The intrapersonal consequences of not confronting prejudice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Shelton, N. J., & Stewart, R. E. (2004). Confronting perpetrators of prejudice: The inhibitory effects of social costs. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 215–222.

Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J., Hood, W. R., & Sherif, C. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The robbers’ cave experiment. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Shook, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Interracial roommate relationships: An experimental field test of the contact hypothesis. Psychological Science, 19(7), 717–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1467–9280.2008.02147.x

Sidanius, J., Sinclair, S., & Pratto, F. (2006). Social dominance orientation, gender, and increasing educational exposure. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(7), 1640–1653.

Sidanius, J., Van Laar, C., Levin, S., & Sinclair, S. (2004). Ethnic enclaves and the dynamics of social identity on the college campus: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(1), 96–110.

Stangor, C., Jonas, K., Stroebe, W., & Hewstone, M. (1996). Development and change of national stereotypes and attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 663–675.

Stephan, W. (1999). Reducing prejudice and stereotyping in schools. New York, NY: Teacher’s College Press.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. J. (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 31–53.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., Fitzgerald, D. C., & Bylsma, W. H. (2003). African American college students’ experiences with everyday racism: Characteristics of and responses to these incidents. Journal of Black Psychology, 29(1), 38–67.

Williams, D. R. (1999). Race, socioeconomics status, and health: The added effect of racism and discrimination. In Adler, N. E., Boyce, T., Chesney, M. A., & Cohen, S. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist, 49, 15-24.

Wright, S. C., Aron, A., McLaughlin-Volpe, T., & Ropp, S. A. (1997). The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 73–90.

- 6424 reads