The Validity of Eyewitness Testimony

One social situation in which the accuracy of our person-perception skills is vitally important is the area of eyewitness testimony (Charman & Wells, 2007; Toglia, Read, Ross, & Lindsay, 2007; Wells, Memon, & Penrod, 2006). Every year, thousands of individuals are charged with and often convicted of crimes based largely on eyewitness evidence. In fact, many people who were convicted prior to the existence of forensic DNA have now been exonerated by DNA tests, and more than 75% of these people were victims of mistaken eyewitness identification (Wells, Memon, & Penrod, 2006; Fisher, 2011).

The judgments of eyewitnesses are often incorrect, and there is only a small correlation between how accurate and how confident an eyewitness is. Witnesses are frequently overconfident, and a person who claims to be absolutely certain about his or her identification is not much more likely to be accurate than someone who appears much less sure, making it almost impossible to determine whether a particular witness is accurate or not (Wells & Olson, 2003).

To accurately remember a person or an event at a later time, we must be able to accurately see and store the information in the first place, keep it in memory over time, and then accurately retrieve it later. But the social situation can influence any of these processes, causing errors and biases.

In terms of initial encoding of the memory, crimes normally occur quickly, often in situations that are accompanied by a lot of stress, distraction, and arousal. Typically, the eyewitness gets only a brief glimpse of the person committing the crime, and this may be under poor lighting conditions and from far away. And the eyewitness may not always focus on the most important aspects of the scene. Weapons are highly salient, and if a weapon is present during the crime, the eyewitness may focus on the weapon, which would draw his or her attention away from the individual committing the crime (Steblay, 1997). In one relevant study, Loftus, Loftus, and Messo (1987) showed people slides of a customer walking up to a bank teller and pulling out either a pistol or a checkbook. By tracking eye movements, the researchers determined that people were more likely to look at the gun than at the checkbook and that this reduced their ability to accurately identify the criminal in a lineup that was given later.

People may be particularly inaccurate when they are asked to identify members of a race other than their own (Brigham, Bennett, Meissner, & Mitchell, 2007). In one field study, for example, Meissner and Brigham (2001) sent European-American, African-American, and Hispanic students into convenience stores in El Paso, Texas. Each of the students made a purchase, and the researchers came in later to ask the clerks to identify photos of the shoppers. Results showed that the clerks demonstrated the own-race bias: they were all more accurate at identifying customers belonging to their own racial or ethnic group, which may be more salient to them, than they were at identifying people from other groups. There seems to be some truth to the adage that “They all look alike”—at least if an individual is looking at someone who is not of his or her own race.

Even if information gets encoded properly, memories may become distorted over time. For one thing, people might discuss what they saw with other people, or they might read information relating to it from other bystanders or in the media. Such postevent information can distort the original memories such that the witnesses are no longer sure what the real information is and what was provided later. The problem is that the new, inaccurate information is highly cognitively accessible, whereas the older information is much less so. The reconstructive memory bias suggests that the memory may shift over time to fit the individual’s current beliefs about the crime. Even describing a face makes it more difficult to recognize the face later (Dodson, Johnson, & Schooler, 1997).

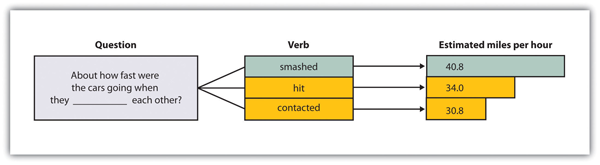

In an experiment by Loftus and Palmer (1974), participants viewed a film of a traffic accident and then, according to random assignment to experimental conditions, answered one of three questions:

- About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?

- About how fast were the cars going when they smashed each other?

- About how fast were the cars going when they contacted each other?

As you can see in in the Figure 2.16, although all the participants saw the same accident, their estimates of the speed of the cars varied by condition. People who had seen the “smashed” question estimated the highest average speed, and those who had seen the “contacted” question estimated the lowest.

Participants viewed a film of a traffic accident and then answered a question about the accident. According to random assignment, the blank was filled by either “hit,” “smashed,” or “contacted” each other. The wording of the question influenced the participants’ memory of the accident. Data are from Loftus and Palmer (1974).

The situation is particularly problematic when the eyewitnesses are children, because research has found that children are more likely to make incorrect identifications than are adults (Pozzulo & Lindsay, 1998) and are also subject to the own-race identification bias (Pezdek, Blandon-Gitlin, & Moore, 2003). In many cases, when sex abuse charges have been filed against babysitters, teachers, religious officials, and family members, the children are the only source of evidence. The possibility that children are not accurately remembering the events that have occurred to them creates substantial problems for the legal system.

Another setting in which eyewitnesses may be inaccurate is when they try to identify suspects from mug shots or lineups. A lineup generally includes the suspect and five to seven other innocent people (the fillers), and the eyewitness must pick out the true perpetrator. The problem is that eyewitnesses typically feel pressured to pick a suspect out of the lineup, which increases the likelihood that they will mistakenly pick someone (rather than no one) as the suspect.

Research has attempted to better understand how people remember and potentially misremember the scenes of and people involved in crimes and to attempt to improve how the legal system makes use of eyewitness testimony. In many states, efforts are being made to better inform judges, juries, and lawyers about how inaccurate eyewitness testimony can be. Guidelines have also been proposed to help ensure that child witnesses are questioned in a nonbiasing way (Poole & Lamb, 1998). Steps can also be taken to ensure that lineups yield more accurate eyewitness identifications. Lineups are more fair when the fillers resemble the suspect, when the interviewer makes it clear that the suspect might or might not be present (Steblay, Dysart, Fulero, & Lindsay, 2001), and when the eyewitness has not been shown the same pictures in a mug-shot book prior to the lineup decision. And several recent studies have found that witnesses who make accurate identifications from a lineup reach their decision faster than do witnesses who make mistaken identifications, suggesting that authorities must take into consideration not only the response but how fast it is given (Dunning & Perretta, 2002).

In addition to distorting our memories for events that have actually occurred, misinformation may lead us to falsely remember information that never occurred. Loftus and her colleagues asked parents to provide them with descriptions of events that did happen (e.g., moving to a new house) and did not happen (e.g., being lost in a shopping mall) to their children. Then (without telling the children which events were real or made up) the researchers asked the children to imagine both types of events. The children were instructed to “think really hard” about whether the events had occurred (Ceci, Huffman, Smith, & Loftus, 1994). More than half of the children generated stories regarding at least one of the made-up events, and they remained insistent that the events did in fact occur even when told by the researcher that they could not possibly have occurred (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). Even college students are susceptible to manipulations that make events that did not actually occur seem as if they did (Mazzoni, Loftus, & Kirsch, 2001).

The ease with which memories can be created or implanted is particularly problematic when the events to be recalled have important consequences. Therapists often argue that patients may repress memories of traumatic events they experienced as children, such as childhood sexual abuse, and then recover the events years later as the therapist leads them to recall the information—for instance, by using dream interpretation and hypnosis (Brown, Scheflin, & Hammond, 1998).

But other researchers argue that painful memories such as sexual abuse are usually very well remembered, that few memories are actually repressed, and that even if they are, it is virtually impossible for patients to accurately retrieve them years later (McNally, Bryant, & Ehlers, 2003; Pope, Poliakoff, Parker, Boynes, & Hudson, 2007). These researchers have argued that the procedures used by the therapists to “retrieve” the memories are more likely to actually implant false memories, leading the patients to erroneously recall events that did not actually occur. Because hundreds of people have been accused, and even imprisoned, on the basis of claims about “recovered memory” of child sexual abuse, the accuracy of these memories has important societal implications. Many psychologists now believe that most of these claims of recovered memories are due to implanted, rather than real, memories (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994).

Taken together, then, the problems of eyewitness testimony represent another example of how social cognition—including the processes that we use to size up and remember other people—may be influenced, sometimes in a way that creates inaccurate perceptions, by the operation of salience, cognitive accessibility, and other information-processing biases.

Key Takeaways

- We use our schemas and attitudes to help us judge and respond to others. In many cases, this is appropriate, but our expectations can also lead to biases in our judgments of ourselves and others.

- A good part of our social cognition is spontaneous or automatic, operating without much thought or effort. On the other hand, when we have the time and the motivation to think about things carefully, we may engage in thoughtful, controlled cognition.

- Which expectations we use to judge others is based on both the situational salience of the things we are judging and the cognitive accessibility of our own schemas and attitudes.

- Variations in the accessibility of schemas lead to biases such as the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, the false consensus bias, biases caused by counterfactual thinking, and those elated to overconfidence.

- The potential biases that are the result of everyday social cognition can have important consequences, both for us in our everyday lives but even for people who make important decisions affecting many other people. Although biases are common, they are not impossible to control, and psychologists and other scientists are working to help people make better decisions.

- The operation of cognitive biases, including the potential for new information to distort information already in memory, can help explain the tendency for eyewitnesses to be overconfident and frequently inaccurate in their recollections of what occurred at crime scenes.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Give an example of a time when you may have committed one of the cognitive heuristics and biases discussed in this chapter. What factors (e.g., availability; salience) caused the error, and what was the outcome of your use of the shortcut or heuristic? What do you see as the general advantages and disadvantages of using this bias in your everyday life? Describe one possible strategy you could use to reduce the potentially harmful effects of this bias in your life.

- Go to the website, which analyzes the extent to which people accurately perceive “streakiness” in sports. Based on the information provided on this site, as well as that in this chapter, in what ways might our sports perceptions be influenced by our expectations and the use of cognitive heuristics and biases?

- Different cognitive heuristics and biases often operate together to influence our social cognition in particular situations. Describe a situation where you feel that two or more biases were affecting your judgment. How did they interact? What combined effects on your social cognition did they have? Which of the heuristics and biases outlined in this chapter do you think might be particularly likely to happen together in social situations and why?

References

Aarts, H., & Dijksterhuis, A. (1999). How often did I do it? Experienced ease of retrieval and frequency estimates of past behavior. ActaPsychologica, 103(1–2), 77–89.

Abbes, M. B. (2012). Does overconfidence explain volatility during the global financial crisis? Transition Studies Review, 19(3), 291-312.

Adams, P. A., & Adams, J. K. (1960). Confidence in the recognition and reproduction of words difficult to spell. American Journal of Psychology, 73, 544–552.

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York: Harper Perennial.

Ariely, D., Loewenstein, D., & Prelec, D. (2003). Coherent arbitrariness: Stable demand curves without stable preferences. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (1), 73–106.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230–244.

Brewer, M. B. (1988). A dual process model of impression formation. In T. K. Srull & R. S. Wyer (Eds.), Advances in social cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 1–36). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brigham, J. C., Bennett, L. B., Meissner, C. A., & Mitchell, T. L. (Eds.). (2007). The influence of race on eyewitness memory. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Brown, D., Scheflin, A. W., & Hammond, D. C. (1998). Memory, trauma treatment, and the law. New York, NY: Norton.

Buehler, R., Griffin, D., & Peetz, J. (2010). The planning fallacy: Cognitive, motivational, and social origins. In M. P. Zanna, J. M. Olson (Eds.) , Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol 43 (pp. 1-62). San Diego, CA US: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(10)43001-4

Byrne, R. M. J., & McEleney, A. (2000). Counterfactual thinking about actions and failures to act. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26(5), 1318–1331.

Ceci, S. J., Huffman, M. L. C., Smith, E., & Loftus, E. F. (1994). Repeatedly thinking about a non-event: Source misattributions among preschoolers. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 3(3–4), 388–407.

Chambers, J. R. (2008). Explaining false uniqueness: Why we are both better and worse than others. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 878–894.

Chang, E. C., Asakawa, K., & Sanna, L. J. (2001). Cultural variations in optimistic and pessimistic bias: Do Easterners really expect the worst and Westerners really expect the best when predicting future life events?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,81(3), 476-491. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.476

Charman, S. D., & Wells, G. L. (2007). Eyewitness lineups: Is the appearance-changes instruction a good idea? Law and Human Behavior, 31(1), 3–22.

Chen, G., Kim, K. A., Nofsinger, J. R., & Rui, O. M. (2007). Trading performance, disposition effect, overconfidence, representativeness bias, and experience of emerging market investors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 20(4), 425-451. doi:10.1002/bdm.561

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2000). Evolutionary psychology and the emotions. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions, 2nd edition (pp. 91-115). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Dijksterhuis, A., Bos, M. W., Nordgren, L. F., & van Baaren, R. B. (2006). On making the right choice: The deliberation-without-attention effect. Science, 311(5763), 1005–1007.

Dodson, C. S., Johnson, M. K., & Schooler, J. W. (1997). The verbal overshadowing effect: Why descriptions impair face recognition. Memory & Cognition, 25(2), 129–139.

Doob, A. N., & Macdonald, G. E. (1979). Television viewing and fear of victimization: Is the relationship causal? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(2), 170–179.

Dunning, D., & Perretta, S. (2002). Automaticity and eyewitness accuracy: A 10- to 12-second rule for distinguishing accurate from inaccurate positive identifications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 951–962.

Dunning, D., Griffin, D. W., Milojkovic, J. D., & Ross, L. (1990). The overconfidence effect in social prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 568–581.

Dunning, D., Johnson, K., Ehrlinger, J., & Kruger, J. (2003). Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 83–87.

Egan, D., Merkle, C., & Weber, M. (in press). Second-order beliefs and the individual investor.Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.

Ehrlinger J., Gilovich, T.D., & Ross, L. (2005). Peering into the bias blind spot: People’s assessments of bias in themselves and others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1-13.

Ferguson, M. J., & Bargh, J. A. (2003). The constructive nature of automatic evaluation. In J. Musch & K. C. Klauer (Eds.),The psychology of evaluation: Affective processes in cognition and emotion (pp. 169–188). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Ferguson, M. J., Hassin, R., & Bargh, J. A. (2008). Implicit motivation: Past, present, and future. In J. Y. Shah & W. L. Gardner (Eds.), Handbook of motivation science (pp. 150–166). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Fisher, R. P. (2011). Editor’s introduction: Special issue on psychology and law. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 4. doi:10.1177/0963721410397654

Forgeard, M. C., & Seligman, M. P. (2012). Seeing the glass half full: A review of the causes and consequences of optimism.PratiquesPsychologiques, 18(2), 107-120. doi:10.1016/j.prps.2012.02.002

Gigerenzer, G. (2004). Fast and frugal heuristics: The tools of founded rationality. In D. J. Koehler & N. Harvey (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making (pp. 62-88). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Gigerenzer, G. (2006). Out of the frying pan and into the fire: Behavioral reactions to terrorist attacks. Risk Analysis, 26, 347-351.

Gilovich, T., Griffin, D., & Kahneman, D. (Eds.). (2002). Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Haddock, G., Rothman, A. J., Reber, R., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Forming judgments of attitude certainty, intensity, and importance: The role of subjective experiences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 771–782.

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106(4), 766-794. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766

Hilton, D. J. (2001). The psychology of financial decision-making: Applications to trading, dealing, and investment analysis. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 2, 37–53. doi: 10.1207/S15327760JPFM0201_4

Hirt, E. R., Kardes, F. R., & Markman, K. D. (2004). Activating a mental simulation mind-set through generation of alternatives: Implications for debiasing in related and unrelated domains. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 374–383.

Hsee, C. K., Hastie, R., & Chen, J. (2008). Hedonomics: Bridging decision research with happiness research. Perspectives On Psychological Science, 3(3), 224-243. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00076.x

Joireman, J., Barnes Truelove, H., & Duell, B. (2010). Effect of outdoor temperature, heat primes and anchoring on belief in global warming. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 358–367.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux.

Kassam, K. S., Koslov, K., & Mendes, W. B. (2009). Decisions under distress: Stress profiles influence anchoring and adjustment. Psychological Science, 20(11), 1394–1399.

Krueger, J., & Clement, R. W. (1994). The truly false consensus effect: An ineradicable and egocentric bias in social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 596–610.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Freund, T. (1983). The freezing and unfreezing of lay inferences: Effects on impressional primacy, ethnic stereotyping, and numerical anchoring. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 448–468.

Lehman, D. R., Lempert, R. O., & Nisbett, R. E. (1988). The effects of graduate training on reasoning: Formal discipline and thinking about everyday-life events. American Psychologist, 43(6), 431–442.

Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 267–286.

Loftus, E. F., & Ketcham, K. (1994). The myth of repressed memory: False memories and allegations of sexual abuse (1st ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 13(5), 585–589.

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25(12), 720–725.

Loftus, E. F., Loftus, G. R., & Messo, J. (1987). Some facts about “weapon focus.” Law and Human Behavior, 11(1), 55–62.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., Loftus, E. F., & Kirsch, I. (2001). Changing beliefs about implausible autobiographical events: A little plausibility goes a long way. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 7(1), 51–59.

McArthur, L. Z., & Post, D. L. (1977). Figural emphasis and person perception. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(6), 520–535.

McNally, R. J., Bryant, R. A., & Ehlers, A. (2003). Does early psychological intervention promote recovery from posttraumatic stress? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(2), 45–79.

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F., & Gilovich, T. (1995). When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 603–610.

Meissner, C. A., & Brigham, J. C. (2001). Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: A meta-analytic review. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7(1), 3–35.

Miller, D. T., Turnbull, W., & McFarland, C. (1988). Particularistic and universalistic evaluation in the social comparison process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 908–917.

Moore, M. T., & Fresco, D. M. (2012). Depressive realism: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 496-509. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.004

Oskamp, S. (1965). Overconfidence in case-study judgments. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29(3), 261-265.

Pezdek, K., Blandon-Gitlin, I., & Moore, C. (2003). Children’s face recognition memory: More evidence for the cross-race effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 760–763.

Poole, D. A., & Lamb, M. E. (1998). The development of interview protocols. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pope, H. G., Jr., Poliakoff, M. B., Parker, M. P., Boynes, M., & Hudson, J. I. (2007). Is dissociative amnesia a culture-bound syndrome? Findings from a survey of historical literature. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences, 37(2), 225–233.

Pozzulo, J. D., & Lindsay, R. C. L. (1998). Identification accuracy of children versus adults: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 22(5), 549–570.

Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science, 9(1), 45–48.

Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 133–148.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The false consensus effect: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 279–301.

Ross, M., & Sicoly, F. (1979). Egocentric biases in availability and attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(3), 322–336.

Schwarz, N., & Vaughn, L. A. (Eds.). (2002). The availability heuristic revisited: Ease of recall and content of recall as distinct sources of information. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 195–202.

Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias: A tour of the irrationally positive brain. New York: Pantheon Books.

Sloman, S. A. (Ed.). (2002). Two systems of reasoning. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Slovic, P. (Ed.). (2000). The perception of risk. London, England: Earthscan Publications.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (Eds.). (2002). Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Steblay, N. M. (1997). Social influence in eyewitness recall: A meta-analytic review of lineup instruction effects. Law and Human Behavior, 21(3), 283–297.

Steblay, N., Dysart, J., Fulero, S., & Lindsay, R. C. L. (2001). Eyewitness accuracy rates in sequential and simultaneous lineup presentations: A meta-analytic comparison. Law and Human Behavior, 25(5), 459–473.

Taylor, S. E., & Fiske, S. T. (1978). Salience, attention and attribution: Top of the head phenomena. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 11, 249–288.

Toglia, M. P., Read, J. D., Ross, D. F., & Lindsay, R. C. L. (Eds.). (2007).The handbook of eyewitness psychology (Vols. 1 & 2). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207–232.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Wells, G. L., & Olson, E. A. (2003). Eyewitness testimony. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 277–295.

Wells, G. L., Memon, A., & Penrod, S. D. (2006). Eyewitness evidence: Improving its probative value. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(2), 45–75.

West, R. F., Meserve, R. J., & Stanovich, K. E. (2012). Cognitive sophistication does not attenuate the bias blind spot. Journal Of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(3), 506-519. doi:10.1037/a0028857

Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-Ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592–598.

Winkielman, P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Mind at ease puts a smile on the face: Psychophysiological evidence that processing facilitation elicits positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 989–1000.

Winkielman, P., Schwarz, N., & Nowak, A. (Eds.). (2002). Affect and processing dynamics: Perceptual fluency enhances evaluations. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- 6027 reads