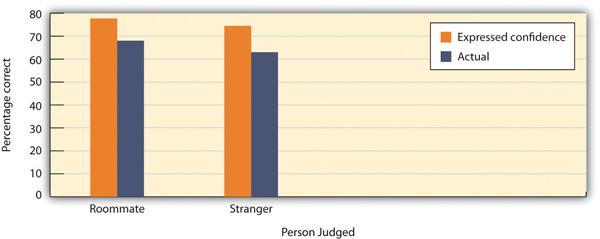

Still another potential judgmental bias, and one that has powerful and often negative effects on our judgments, is the overconfidence bias, a tendency to be overconfident in our own skills, abilities, and judgments. We often have little awareness of our own limitations, leading us to act as if we are more certain about things than we should be, particularly on tasks that are difficult. Adams and Adams (1960) found that for words that were difficult to spell, people were correct in spelling them only about 80% of the time, even though they indicated that they were “100% certain” that they were correct. David Dunning and his colleagues (Dunning, Griffin, Milojkovic, & Ross, 1990) asked college students to predict how another student would react in various situations. Some participants made predictions about a fellow student whom they had just met and interviewed, and others made predictions about their roommates. In both cases, participants reported their confidence in each prediction, and accuracy was determined by the responses of the target persons themselves. The results were clear: regardless of whether they judged a stranger or a roommate, the students consistently overestimated the accuracy of their own predictions (Figure 2.14).

Making matters even worse, Kruger and Dunning (1999) found that people who scored low rather than high on tests of spelling, logic, grammar, and humor appreciation were also most likely to show overconfidence by overestimating how well they would do. Apparently, poor performers are doubly cursed—they not only are unable to predict their own skills but also are the most unaware that they can’t do so (Dunning, Johnson, Ehrlinger, & Kruger, 2003).

The tendency to be overconfident in our judgments can have some very negative effects. When eyewitnesses testify in courtrooms regarding their memories of a crime, they often are completely sure that they are identifying the right person. But their confidence doesn’t correlate much with their actual accuracy. This is, in part, why so many people have been wrongfully convicted on the basis of inaccurate eyewitness testimony given by overconfident witnesses (Wells & Olson, 2003). Overconfidence can also spill over into professional judgments, for example, in clinical psychology (Oskamp, 1965) and in market investment and trading (Chen, Kim, Nofsinger, & Rui, 2007). Indeed, in regards to our case study at the start of this chapter, the role of overconfidence bias in the financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath has been well documented (Abbes, 2012).

This overconfidence also often seems to apply to social judgments about the future in general. A pervasive optimistic bias has been noted in members of many cultures (Sharot, 2011), which can be defined as a tendency to believe that positive outcomes are more likely to happen than negative ones, particularly in relation to ourselves versus others. Importantly, this optimism is often unwarranted. Most people, for example, underestimate their risk of experiencing negative events like divorce and illness, and overestimate the likelihood of positive ones, including gaining a promotion at work or living to a ripe old age (Schwarzer, 1994). There is some evidence of diversity in regards to optimism, however, across different groups. People in collectivist cultures tend not to show this bias to the same extent as those living in individualistic ones (Chang, Asakawa, & Sanna, 2001). Moreover, individuals who have clinical depression have been shown to evidence a phenomenon termed depressive realism, whereby their social judgments about the future are less positively skewed and often more accurate than those who do not have depression (Moore & Fresco, 2012).

The optimistic bias can also extend into the planning fallacy, defined as a tendency to overestimate the amount that we can accomplish over a particular time frame. This fallacy can also entail the underestimation of the resources and costs involved in completing a task or project, as anyone who has attempted to budget for home renovations can probably attest to. Everyday examples of the planning fallacy abound, in everything from the completion of course assignments to the construction of new buildings. On a grander scale, newsworthy items in any country hosting a major sporting event, for example, the Olympics or World Cup soccer always seem to include the spiralling budgets and overrunning timelines as the events approach.

Why is the planning fallacy so persistent? Several factors appear to be at work here. Buehler, Griffin and Peetz (2010) argue that when planning projects, individuals orient to the future and pay too little attention to their past relevant experiences. This can cause them to overlook previous occasions where they experienced difficulties and over-runs. They also tend to plan for what time and resources are likely to be needed, if things run as planned. That is, they do not spend enough time thinking about all the things that might go wrong, for example, all the unforeseen demands on their time and resources that may occur during the completion of the task. Worryingly, the planning fallacy seems to be even stronger for tasks where we are highly motivated and invested in timely completions. It appears that wishful thinking is often at work here (Buehler et al., 2010). For some further perspectives on the advantages and disadvantages of the optimism bias, see this engaging TED Talk by Tali Sharot.

If these biases related to overconfidence appear at least sometimes to lead us to inaccurate social judgments, a key question here is why are they so pervasive? What functions do they serve? One possibility is that they help to enhance people’s motivation and self-esteem levels. If we have a positive view of our abilities and judgments, and are confident that we can execute tasks to deadlines, we will be more likely to attempt challenging projects and to put ourselves forward for demanding opportunities. Moreover, there is consistent evidence that a mild degree of optimism can predict a range of positive outcomes, including success and even physical health (Forgeard & Seligman, 2012).

- 2991 reads