Let’s return once more to our friend Joachim and imagine that we now discover that over the next two weeks he has spent virtually every night at clubs listening to music rather than studying. And these behaviors are starting to have some severe consequences: he just found out that he’s failed his biology midterm. How will he ever explain that to his parents? What were at first relatively small discrepancies between self-concept and behavior are starting to snowball, and they are starting to have more affective consequences. Joachim is realizing that he’s in big trouble—the inconsistencies between his prior attitudes about the importance of schoolwork and his behavior are creating some significant threats to his positive self-esteem. As we saw in our discussion of self-awareness theory, this discomfort that occurs when we behave in ways that we see as inconsistent, such as when we fail to live up to our own expectations, is called cognitive dissonance (Cooper, 2007; Festinger, 1957; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999). The discomfort of cognitive dissonance is experienced as pain, showing up in a part of the brain that is particularly sensitive to pain—the anterior cingulate cortex (van Veen, Krug, Schooler, & Carter, 2009).

Leon Festinger and J. Merrill Carlsmith (1959) conducted an important study designed to demonstrate the extent to which behaviors that are discrepant from our initial beliefs can create cognitive dissonance and can influence attitudes. College students participated in an experiment in which they were asked to work on a task that was incredibly boring (such as turning pegs on a peg board) and lasted for a full hour. After they had finished the task, the experimenter explained that the assistant who normally helped convince people to participate in the study was unavailable and that he could use some help persuading the next person that the task was going to be interesting and enjoyable. The experimenter explained that it would be much more convincing if a fellow student rather than the experimenter delivered this message and asked the participant if he would be willing do to it. Thus with his request the experimenter induced the participants to lie about the task to another student, and all the participants agreed to do so.

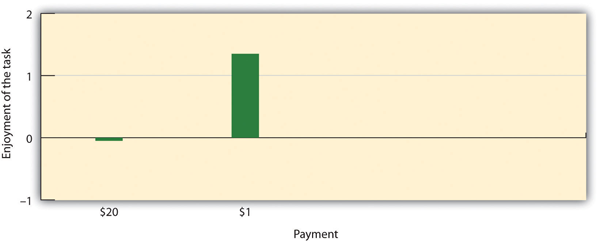

The experimental manipulation involved the amount of money the students were paid to tell the lie. Half of the students were offered a large payment ($20) for telling the lie, whereas the other half were offered only a small payment ($1) for telling the lie. After the participants had told the lie, an interviewer asked each of them how much they had enjoyed the task they had performed earlier in the experiment. As you can see in Figure 4.10, Festinger and Carlsmith found that the students who had been paid $20 for saying the tasks had been enjoyable rated the task as very boring, which indeed it was. In contrast, the students who were paid only $1 for telling the lie changed their attitude toward the task and rated it as significantly more interesting.

Festinger explained the results of this study in terms of consistency and inconsistency among cognitions. He hypothesized that some thoughts might be dissonant, in the sense that they made us feel uncomfortable, while other thoughts were more consonant, in the sense that they made us feel good. He argued that people may feel an uncomfortable state (which he called cognitive dissonance) when they have many dissonant thoughts—for instance, between the idea that (a) they are smart and decent people and (b) they nevertheless told a lie to another student for only a small payment.

Festinger argued that the people in his experiment who had been induced to lie for only $1 experienced more cognitive dissonance than the people who were paid $20 because the latter group had a strong external justification for having done it whereas the former did not. The people in the $1 condition, Festinger argued, needed to convince themselves that that the task was actually interesting to reduce the dissonance they were experiencing.

Although originally considered in terms of the inconsistency among different cognitions, Festinger’s theory has also been applied to the negative feelings that we experience when there is inconsistency between our attitudes and our behavior, and particularly when the behavior threatens our perceptions of ourselves as good people (Aronson, 1969). Thus Joachim is likely feeling cognitive dissonance because he has acted against his better judgment and these behaviors are having some real consequences for him. The dissonant thoughts involve (a) his perception of himself as a hardworking student, compared with (b) his recent behaviors that do not support that idea. Our expectation is that Joachim will not enjoy these negative feelings and will attempt to get rid of them.

- 5064 reads