Still another determinant of conformity is the perceived importance of the decision. The studies of Sherif, Asch, and Moscovici may be criticized because the decisions that the participants made—for instance, judging the length of lines or the colors of objects—seem rather trivial. But what would happen when people were asked to make an important decision? Although you might think that conformity would be less when the task becomes more important (perhaps because people would feel uncomfortable relying on the judgments of others and want to take more responsibility for their own decisions), the influence of task importance actually turns out to be more complicated than that.

Research Focus: How Task Importance and Confidence Influence Conformity

The joint influence of an individual’s confidence in his or her beliefs and the importance of the task was demonstrated in an experiment conducted by Baron, Vandello, and Brunsman (1996) that used a slight modification of the Asch procedure to assess conformity. Participants completed the experiment along with two other students, who were actually experimental confederates. The participants worked on several different types of trials, but there were 26 that were relevant to the conformity predictions. On these trials, a photo of a single individual was presented first, followed immediately by a “lineup” photo of four individuals, one of whom had been viewed in the initial slide (but who might have been dressed differently):

The participants’ task was to call out which person in the lineup was the same as the original individual using a number between 1 (the person on the far left) and 4 (the person on the far right). In each of the critical trials, the two confederates went before the participant and they each gave the same wrong response. Two experimental manipulations were used. First, the researchers manipulated task importance by telling some participants (the high-importance condition) that their performance on the task was an important measure of eyewitness ability and that the participants who performed most accurately would receive $20 at the end of the data collection. (A lottery using all the participants was actually held at the end of the semester, and some participants were paid the $20.) Participants in the low-importance condition, on the other hand, were told that the test procedure was part of a pilot study and that the decisions were not that important. Second, task difficulty was varied by showing the test and the lineup photos for 5 and 10 seconds, respectively (easy condition) or for only ½ and 1 second, respectively (difficult condition). The conformity score was defined as the number of trials in which the participant offered the same (incorrect) response as the confederates.

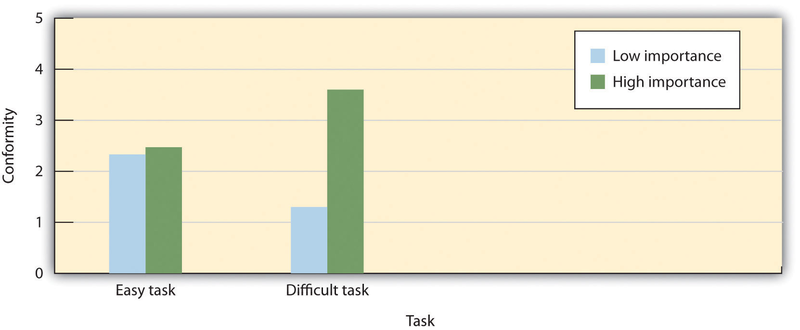

On easy tasks, participants conformed less when they thought that the decision was of high (versus low) importance, whereas on difficult tasks, participants conformed more when they thought the decision was of high importance. Data are from Baron et al. (1996). As you can see in Figure 6.8, an interaction between task difficulty and task importance was observed. On easy tasks, participants conformed less to the incorrect judgments of others when the decision had more important consequences for them. In these cases, they seemed to rely more on their own opinions (which they were convinced were correct) when it really mattered, but were more likely to go along with the opinions of the others when things were not that critical (probably a result of normative social influence). On the difficult tasks, however, results were the opposite. In this case, participants conformed more when they thought the decision was of high, rather than low, importance. In the cases in which they were more unsure of their opinions and yet they really wanted to be correct, they used the judgments of others to inform their own views (informational social influence).

Key Takeaways

- Social influence creates conformity.

- Influence may occur in more passive or more active ways.

- We conform both to gain accurate knowledge (informational social influence) and to avoid being rejected by others (normative social influence).

- Both majorities and minorities may create social influence, but they do so in different ways.

- The characteristics of the social situation, including the number of people in the majority and the unanimity of the majority, have a strong influence on conformity.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Describe a time when you conformed to the opinions or behaviors of others. Interpret the conformity in terms of informational and/or normative social influence.

- Imagine you were serving on a jury in which you found yourself the only person who believed that the defendant was innocent. What strategies might you use to convince the majority?

References

Allen, V. L. (1975). Social support for nonconformity. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 8). New York, NY: Academic Press;

Allen, V. L., & Levine, J. M. (1968). Social support, dissent and conformity. Sociometry, 31(2), 138–149.

Anderson, C., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2003). Emotional convergence between people over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 1054–1068.

Asch, S. E. (1952). Social psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall;

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 11, 32.

Baron, R. S., Vandello, J. A., & Brunsman, B. (1996). The forgotten variable in conformity research: Impact of task importance on social influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 915–927.

Boyanowsky, E. O., & Allen, V. L. (1973). Ingroup norms and self-identity as determinants of discriminatory behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25, 408–418.

Chartrand, T. L., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 893–910.

Chartrand, T. L., & Dalton, A. N. (2009). Mimicry: Its ubiquity, importance, and functionality. In E. Morsella, J. A. Bargh, & P. M. Gollwitzer (Eds.), Oxford handbook of human action (pp. 458–483). New York, NY: Oxford University Press;

Cialdini, R. B. (1993). Influence: Science and practice (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins; Sherif, M. (1936).The psychology of social norms. New York, NY: Harper & Row;

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1015–1026.

Crano, W. D., & Chen, X. (1998). The leniency contract and persistence of majority and minority influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1437–1450.

Dalton, A. N., Chartrand, T. L., & Finkel, E. J. (2010). The schema-driven chameleon: How mimicry affects executive and self-regulatory resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 605–617.

Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51, 629–636.

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups. New York, NY: Harper;

Hardin, C., & Higgins, T. (1996). Shared reality: How social verification makes the subjective objective. In R. M. Sorrentino & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (Vol. 3, pp. 28–84). New York, NY: Guilford;

Hogg, M. A. (2010). Influence and leadership. In S. F. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 1166–1207). New York, NY: Wiley.

Jacobs, R. C., & Campbell, D. T. (1961). The perpetuation of an arbitrary tradition through several generations of a laboratory microculture. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62, 649–658.

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36, 343–356;

MacNeil, M. K., & Sherif, M. (1976). Norm change over subject generations as a function of arbitrariness of prescribed norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 762–773.

Martin, R., & Hewstone, M. (2003). Majority versus minority influence: When, not whether, source status instigates heuristic or systematic processing. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(3), 313–330;

Martin, R., Martin, P. Y., Smith, J. R., & Hewstone, M. (2007). Majority versus minority influence and prediction of behavioral intentions and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(5), 763–771.

Milgram, S., Bickman, L., & Berkowitz, L. (1969). Note on the drawing power of crowds of different size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13, 79–82.

Moscovici, S., Lage, E., & Naffrechoux, M. (1969). Influence of a consistent minority on the responses of a majority in a colour perception task.Sociometry, 32, 365–379.

Mugny, G., & Papastamou, S. (1981). When rigidity does not fail: Individualization and psychologicalization as resistance to the diffusion of minority innovation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 43–62.

Mullen, B. (1983). Operationalizing the effect of the group on the individual: A self-attention perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 295–322.

Nemeth, C. J., & Kwan, J. L. (1987). Minority influence, divergent thinking, and the detection of correct solutions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17, 788–799.

Rohrer, J. H., Baron, S. H., Hoffman, E. L., & Swander, D. V. (1954). The stability of autokinetic judgments. American Journal of Psychology, 67, 143–146.

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways. Boston, MA: Ginn.

Tickle-Degnen, L., & Rosenthal, R. (1990). The nature of rapport and its nonverbal correlates. Psychological Inquiry, 1(4), 285–293;

Tickle-Degnen, L., & Rosenthal, R. (Eds.). (1992). Nonverbal aspects of therapeutic rapport. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Turner, J. C. (1991). Social influence. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks Cole.

Wilder, D. A. (1977). Perception of groups, size of opposition, and social influence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 253–268.

- 9203 reads