One common decision-making task of groups is to come to a consensus regarding a judgment, such as where to hold a party, whether a defendant is innocent or guilty, or how much money a corporation should invest in a new product. Whenever a majority of members in the group favors a given opinion, even if that majority is very slim, the group is likely to end up adopting that majority opinion. Of course, such a result would be expected, since, as a result of conformity pressures, the group’s final judgment should reflect the average of group members’ initial opinions.

Although groups generally do show pressures toward conformity, the tendency to side with the majority after group discussion turns out to be even stronger than this. It is commonly found that groups make even more extreme decisions, in the direction of the existing norm, than we would predict they would, given the initial opinions of the group members. Group polarization is said to occur when, after discussion, the attitudes held by the individual group members become more extreme than they were before the group began discussing the topic (Brauer, Judd, & Gliner, 2006; Myers, 1982). This may seem surprising, given the widespread belief that groups tend to push people toward consensus and the middle-ground in decision making. Actually, they may often lead to more extreme decisions being made than those that individuals would have taken on their own.

Group polarization was initially observed using problems in which the group members had to indicate how an individual should choose between a risky, but very positive, outcome and a certain, but less desirable, outcome (Stoner, 1968). Consider the following question:

Frederica has a secure job with a large bank. Her salary is adequate but unlikely to increase. However, Frederica has been offered a job with a relatively unknown startup company in which the likelihood of failure is high and in which the salary is dependent upon the success of the company. What is the minimum probability of the startup company’s success that you would find acceptable to make it worthwhile for Frederica to take the job? (choose one)

1 in 10, 3 in 10, 5 in 10, 7 in 10, 9 in 10

Research has found group polarization on these types of decisions, such that the group recommendation is more risky (in this case, requiring a lower probability of success of the new company) than the average of the individual group members’ initial opinions. In these cases, the polarization can be explained partly in terms of diffusion of responsibility (Kogan & Wallach, 1967). Because the group as a whole is taking responsibility for the decision, the individual may be willing to take a more extreme stand, since he or she can share the blame with other group members if the risky decision does not work out.

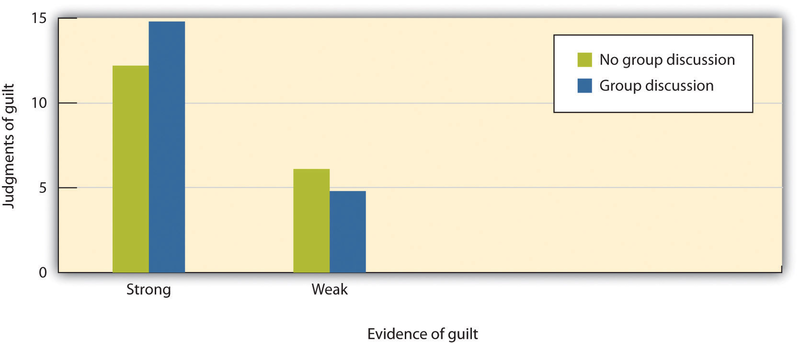

But group polarization is not limited to decisions that involve risk. For instance, in an experiment by Myers and Kaplan (1976), groups of students were asked to assess the guilt or innocence of defendants in traffic cases. The researchers also manipulated the strength of the evidence against the defendant, such that in some groups the evidence was strong and in other groups the evidence was weak. This resulted in two groups of juries—some in which the majority of the students initially favored conviction (on the basis of the strong evidence) and others in which a majority initially favored acquittal (on the basis of only weak evidence). The researchers asked the individuals to express their opinions about the guilt of the defendant both before and after the jury deliberated.

As you can see in Figure 10.11, the opinions that the individuals held about the guilt or innocence of the defendants were found to be more extreme after discussion than they were, on average, before the discussion began. That is, members of juries in which the majority of the individuals initially favored conviction became more likely to believe the defendant was guilty after the discussion, and members of juries in which the majority of the individuals initially favored acquittal became more likely to believe the defendant was innocent after the discussion. Similarly, Myers and Bishop (1970) found that groups of college students who had initially racist attitudes became more racist after group discussion, whereas groups of college students who had initially antiracist attitudes became less racist after group discussion. Similar findings have been found for groups discussing a very wide variety of topics and across many different cultures.

The juries in this research were given either strong or weak evidence about the guilt of a defendant and then were either allowed or not allowed to discuss the evidence before making a final decision. Demonstrating group polarization, the juries that discussed the case made significantly more extreme decisions than did the juries that did not discuss the case. Data are from Myers and Kaplan (1976).

Group polarization does not occur in all groups and in all settings but tends to happen most often when two conditions are present: First, the group members must have an initial leaning toward a given opinion or decision. If the group members generally support liberal policies, their opinions are likely to become even more liberal after discussion. But if the group is made up equally of both liberals and conservatives, group polarization would not be expected. Second, group polarization is strengthened by discussion of the topic. For instance, in the research by Myers and Kaplan (1976) just reported, in some experimental conditions, the group members expressed their opinions but did not discuss the issue, and these groups showed less polarization than groups that discussed the issue.

Group polarization has also been observed in important real-world contexts, including financial decision making in corporate boardrooms (Cheng & Chiou, 2008; Zhu, 2010). It has also been argued that the recent polarization in political attitudes in many countries, for example in the United States between the “blue” Democratic states versus the “red” Republican states, is occurring in large part because each group spends time communicating with other like-minded group members, leading to more extreme opinions on each side. And some have argued that terrorist groups develop their extreme positions and engage in violent behaviors as a result of the group polarization that occurs in their everyday interactions (Drummond, 2002; McCauley, 1989). As the group members, all of whom initially have some radical beliefs, meet and discuss their concerns and desires, their opinions polarize, allowing them to become progressively more extreme. Because they are also away from any other influences that might moderate their opinions, they may eventually become mass killers.

Group polarization is the result of both cognitive and affective factors. The general idea of the persuasive arguments approach to explaining group polarization is cognitive in orientation. This approach assumes that there is a set of potential arguments that support any given opinion and another set of potential arguments that refute that opinion. Furthermore, an individual’s current opinion about the topic is predicted to be based on the arguments that he or she is currently aware of. During group discussion, each member presents arguments supporting his or her individual opinions. And because the group members are initially leaning in one direction, it is expected that there will be many arguments generated that support the initial leaning of the group members. As a result, each member is exposed to new arguments supporting the initial leaning of the group, and this predominance of arguments leaning in one direction polarizes the opinions of the group members (Van Swol, 2009). Supporting the predictions of persuasive arguments theory, research has shown that the number of novel arguments mentioned in discussion is related to the amount of polarization (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978) and that there is likely to be little group polarization without discussion (Clark, Crockett, & Archer, 1971). Notice here the parallels between the persuasive arguments approach to group polarization and the concept of informational conformity.

But group polarization is in part based on the affective responses of the individuals—and particularly the social identity they receive from being good group members (Hogg, Turner, & Davidson, 1990; Mackie, 1986; Mackie & Cooper, 1984). The idea here is that group members, in their desire to create positive social identity, attempt to differentiate their group from other implied or actual groups by adopting extreme beliefs. Thus the amount of group polarization observed is expected to be determined not only by the norms of the ingroup but also by a movement away from the norms of other relevant outgroups. In short, this explanation says that groups that have well-defined (extreme) beliefs are better able to produce social identity for their members than are groups that have more moderate (and potentially less clear) beliefs. Once again, notice the similarity of this account of polarization to the notion of normative conformity.

Group polarization effects are stronger when the group members have high social identity (Abrams, Wetherell, Cochrane, & Hogg, 1990; Hogg, Turner, & Davidson, 1990; Mackie, 1986). Diane Mackie (1986) had participants listen to three people discussing a topic, supposedly so that they could become familiar with the issue themselves to help them make their own decisions. However, the individuals that they listened to were said to be members of a group that they would be joining during the upcoming experimental session, members of a group that they were not expecting to join, or some individuals who were not a group at all. Mackie found that the perceived norms of the (future) ingroup were seen as more extreme than those of the other group or the individuals, and that the participants were more likely to agree with the arguments of the ingroup. This finding supports the idea that group norms are perceived as more extreme for groups that people identify with (in this case, because they were expecting to join it in the future). And another experiment by Mackie (1986) also supported the social identity prediction that the existence of a rival outgroup increases polarization as the group members attempt to differentiate themselves from the other group by adopting more extreme positions.

Taken together then, the research reveals that another potential problem with group decision making is that it can be polarized. These changes toward more extreme positions have a variety of causes and occur more under some conditions than others, but they must be kept in mind whenever groups come together to make important decisions.

- 4525 reads