Aggression occurs when we feel that we are being threatened by others, and thus personality variables that relate to perceived threat also predict aggression. Aggression is particularly likely among people who feel that they are being rejected by others whom they care about (Downey, Irwin, Ramsay, & Ayduk, 2004). In addition, people who experience a lot of negative affect, and particularly those who tend to perceive others as threatening, are likely to be aggressive (Crick & Dodge, 1994). When these people see behavior that may or may not be hostile in intent, they tend to perceive it as aggressive, and these perceptions can increase their aggression.

People also differ in their general attitudes toward the appropriateness of using violence. Some people are simply more likely to believe in the value of using aggression as a means of solving problems than are others. For many people, violence is a perfectly acceptable method of dealing with interpersonal conflict, and these people are more aggressive (Anderson, 1997; Dill, Anderson, & Deuser, 1997). The social situation that surrounds people also helps determine their beliefs about aggression. Members of youth gangs find violence to be acceptable and normal (Baumeister, Smart, & Boden, 1996), and membership in the gang reinforces these beliefs. For these individuals, the important goals are to be respected and feared, and engaging in violence is an accepted means to this end (Horowitz & Schwartz, 1974).

Perhaps you believe that people with low self-esteem would be more aggressive than those with high self-esteem. In fact, the opposite is true. Research has found that individuals with inflated or unstable self-esteem are more prone to anger and are highly aggressive when their high self-image is threatened (Kernis, Brockner, & Frankel, 1989; Baumeister et al., 1996). For instance, classroom bullies are those who always want to be the center of attention, who think a lot of themselves, and who cannot take criticism (Salmivalli & Nieminen, 2002). It appears that these people are highly motivated to protect their inflated self-concepts and react with anger and aggression when it is threatened.

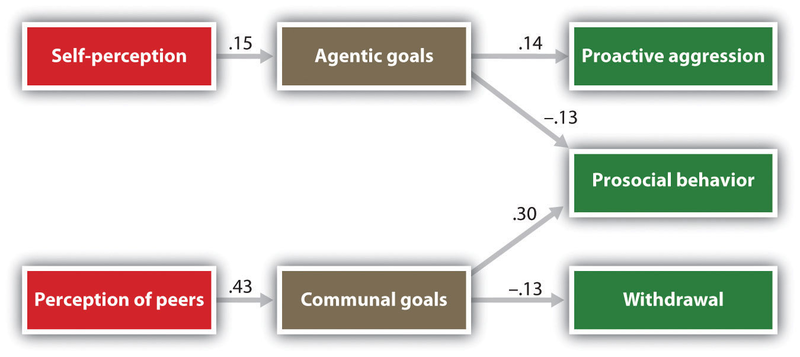

Children who saw themselves, and who were seen by peers, as having self-concerned motives were more aggressive and less altruistic than were children who were rated as more caring of others. Data are from Salmivalli et al. (2005).

Underlying these observed individual differences in aggression are the fundamental motives of self-concern and other-concern. Salmivalli, Ojanen, Haanpaa, and Peets (2005) asked fifth- and sixth-grade children to complete a number of measures describing themselves and their preferred relationships with others. In addition, each of the children was given a roster of the other students in their class and was asked to check off the names of the children who were most aggressive and most helpful. As you can see in Figure 9.11, the underlying personality orientations of the children influenced how they were perceived by their classmates, and in a way that fits well with our knowledge about the role of self-concern and other-concern. Children who rated goals of self-concern highly (agreeing that it was important, for instance, that “others respect and admire me”) were more likely to be rated as acting aggressively, whereas children for whom other-concern was seen as more important (agreeing with statements such as “I feel close to others”) were more likely to be seen as altruistic.

- 5357 reads