Learning Objectives

- Describe how people use behaviors and traits to form initial perceptions of others.

- Explore research about forming impressions from thin slices of information.

- Summarize the role of nonverbal behaviors in person perception.

- Review research about detecting deception.

People are often very skilled at person perception—the process of learning about other people—and our brains are designed to help us judge others efficiently (Haselton & Funder, 2006; Macrae & Quadflieg, 2010). Infants prefer to look at faces of people more than they do other visual patterns, and children quickly learn to identify people and their emotional expressions (Turati, Cassia, Simion, & Leo, 2006). As adults, we are able to identify and remember a potentially unlimited number of people as we navigate our social environments (Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini, 2000), and we form impressions of those others quickly and without much effort (Carlston & Skowronski, 2005; Fletcher-Watson, Findlay, Leekam, & Benson, 2008). Furthermore, our first impressions are, at least in some cases, remarkably accurate (Ambady, Bernieri, & Richeson, 2000).

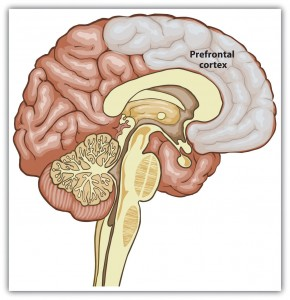

Recent research is beginning to uncover the areas in our brain where person perception occurs. In one relevant study, Mason and Macrae (2004) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans to test whether people stored information about other people in a different location in the brain than where they stored information about animals, and they found that this was the case. Specific areas of the prefrontal cortex were found to be more active when people made judgments about people rather than dogs (Figure 5.2).

Learning about people is a lot like learning about any other object in our environment, with one major exception. With an object, there is no interaction: we learn about the characteristics of a car or a cell phone, for example, without any concern that the car or the phone is learning about us. It is a one-way process. With people, in contrast, there is a two-way social process: just as we are learning about another person, that person is learning about us, or potentially attempting to keep us from accurately perceiving him or her. For instance, research has found that when other people are looking directly at us, we process their features more fully and faster, and we remember them better than when the same people are not looking at us (Hood & Macrae, 2007).

In the social dynamic with others, then, we have two goals: first, we need to learn about them, and second, we want them to learn about us (and, we hope, like and respect us). Our focus here is on the former process—how we make sense of other people. But remember that just as you are judging them, they are judging you.

We have seen in the chapter, The Self, that when people are asked to describe themselves, they generally do so in terms of their physical features (“I am really tall”), social category memberships (“I am a woman”), and traits (“I am friendly”). These characteristics well reflect the dimensions we use when we try to form impressions of others. In this section, we will review how we initially use the physical features and social category memberships of others (e.g., male or female, race, and ethnicity) to form judgments and then will focus on the role of personality traits in person perception.

Research Focus: Forming Impressions from Thin Slices

Although it might seem surprising, social psychological research has demonstrated that at least in some limited situations, people can draw remarkably accurate conclusions about others on the

basis of very little data, and that they can do this very quickly (Rule & Ambady, 2010; Rule, Ambady, Adams, & Macrae, 2008; Rule, Ambady, & Hallett, 2009). Ambady and Rosenthal

(1993) made videotapes of six female and seven male graduate students while they were teaching an undergraduate course. The courses covered diverse areas of the college curriculum, including

humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. For each instructor, three 10-second video clips were taken—10 seconds from the first 10 minutes of the class, 10 seconds from the middle of

the class, and 10 seconds from the last 10 minutes of the class. Nine female undergraduates were asked to rate the 39 clips of the instructors individually on 15 dimensions, such as

“optimistic,” “confident,” “active,” and so on, as well as give an overall, global rating. Ambady and her colleagues then compared the ratings of the instructors made by the participants who

had seen the instructors for only 30 seconds with the ratings of the same instructors that had been made by actual students who had spent a whole semester with the instructors and who had

rated them at the end of the semester on dimensions such as “the quality of the course section” and “the section leader’s performance.” The researchers used the Pearson correlation

coefficient to make the comparison (remember that correlations nearer +1.0 or –1.0 are stronger). As you can see in the following table, the ratings of the participants and the ratings of the

students were highly positively correlated.

|

Correlations of Molar Nonverbal Behaviors with College Teacher Effectiveness Ratings (Student Ratings) |

|

|

Variable |

r |

|

Accepting |

0.5 |

|

Active |

.77** |

|

Attentive |

0.48 |

|

Competent |

.56* |

|

Confident |

.82*** |

|

Dominant |

.79** |

|

Empathic |

0.45 |

|

Enthusiastic |

.76** |

|

Honest |

0.32 |

|

Likable |

.73** |

|

(Not) Anxious |

0.26 |

|

Optimistic |

.84*** |

|

Professional |

0.53 |

|

Supportive |

.55* |

|

Warm |

.67* |

|

Global Variable |

.76** |

|

*p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001. Data are from Ambady and Rosenthal (1993). Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1993). Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3), 431–441. |

|

If the finding that we can make accurate judgments about other people in only 30 seconds surprises you, then perhaps you will be even more surprised to learn that we do not even need that

much time. Willis and Todorov (2006) found that even a tenth of a second was enough to make judgments that correlated highly with the same judgments made by other people who were given

several minutes to make the judgments. Other research has found that we can make accurate judgments in seconds or even milliseconds about, for instance, the personalities of salespersons

(Ambady, Krabbenhoft, & Hogan, 2006) and even whether or not a person is prejudiced (Richeson & Shelton, 2005). Todorov, Mandisodza, Goren, and Hall (2005) reported a demonstration of

just how important such initial impressions can be. These researchers showed to participants pairs of political candidates who had run against each other in previous elections for the U.S.

Senate and House of Representatives. Participants saw only the faces of the candidates, and they saw them in some cases for only one second. Their task was to judge which person in of each

pair was the most competent. Todorov and colleagues (2005) found that these judgments predicted the actual result of the election; in fact, 68% of the time the person judged to have the most

competent face won. Rule and Ambady (2010) showed that perceivers were also able to accurately distinguish whether people were Democrats or Republicans based only on photos of their faces.

Republicans were perceived as more powerful than Democrats, and Democrats were perceived as warmer than Republicans. Further, Rule, Ambady, Adams, and Macrae (2008) found that people could

accurately determine the sexual orientation of faces presented in photos (gay or straight) based on their judgments of what they thought “most people” would say. These findings have since

been replicated across different cultures varying in their average acceptance of homosexuality (Rule, Ishii, Ambady, Rosen, & Hallett, 2011).

Taken together, these data confirm that we can form a wide variety of initial impressions of others quickly and, at least in some cases, quite accurately. Of course, in these situations, the people who were being observed were not trying to hide their personalities from the observers. As we saw in Chapter 3, people often use strategic self-presentation quite skillfully, which further complicates the person perception process.

- 5710 reads