You may have noticed when you first looked at the images presented earlier in this chapter that you tended to like some of the people and to dislike others. It is not surprising that you had these emotions—these initial affective reactions are an essential and highly adaptive part of person perception. One of the things that we need to determine when we first perceive someone is whether that person poses any threat to our well-being. We may dislike or experience negative emotions about people because we feel that they are likely to harm us, just as we may like and feel positively about them if we feel that they can help us (Rozin & Royzman, 2001). Research has found that the threat and the trustworthiness of others are particularly quickly perceived, at least by people who are not trying to hide their intentions (Bar, Neta, & Linz, 2006; Todorov, Said, Engel, & Oosterhof, 2008).

Most people with whom we interact are not dangerous, nor do they create problems for us. In fact, when we are asked to rate how much we like complete strangers, we generally rate them positively (Sears, 1986). Because we generally expect people to be positive, people who are negative or threatening are salient, likely to create strong emotional responses, and relatively easy to spot.

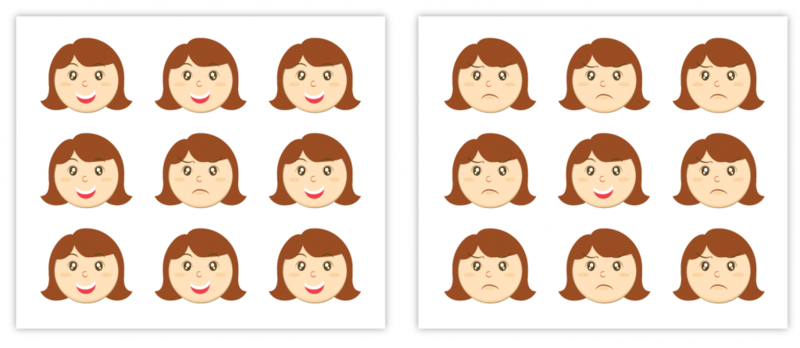

Compared with positive information, negative information about a person tends to elicit more physiological arousal, draw greater attention, and exert greater impact on our judgments and impressions of the person. Hansen and Hansen (1988) had undergraduate students complete a series of trials in which they were shown, for very brief time periods, “crowds” of nine faces (Figure 5.7). On some of the trials, all the faces were happy or all the faces were angry. On other trials, the “crowd” was made up of eight happy faces and one angry face, or eight angry faces and one happy face. For each trial, the participants were instructed to say, as quickly as possible, whether the crowd contained a discrepant face or not. Hansen and Hansen found that the students were significantly faster at identifying the single angry face among the eight happy ones than they were at identifying the single happy face among the eight angry ones. They also made significantly fewer errors doing so. The researchers’ conclusion was that angry, and thus threatening, faces quickly popped out from the crowd. Similarly, Ackerman and colleagues (2006) found that people were better at recognizing the faces of other people when those faces had angry, rather than neutral, expressions, and Dijksterhuis and Aarts (2003) found that people could more quickly and more accurately recognize negative, rather than positive, words.

Because negative faces are more salient and therefore more likely to grab our attention than are positive faces, people are faster at locating a single negative face in a display of positive faces than they are to locate a single positive face in a display of negative faces.

Our brains seem to be hardwired to detect negative behaviors (Adams, Gordon, Baird, Ambady, & Kleck, 2003), and at an evolutionary level this makes sense. It is important to tell the “good guys” from the “bad guys” and to try to avoid interacting with the latter. In one study, Tiffany Ito and her colleagues (Ito, Larsen, Smith, & Cacioppo, 1998) showed college students a series of positive, negative, and neutral images while their event-related brain potentials were collected. The researchers found that different parts of the brain reacted to positive and negative images and that the response to negative images was greater overall. They concluded that “negative information weighs more heavily on the brain” (p. 887). In sum, the results of research in person perception are clear: when we are perceiving people, negative information is simply more influential than positive information (Pratto & John, 1991).

Social Psychology in the Public Interest: Detecting Deception

One important person perception task that we must all engage in sometimes is to try to determine whether other people are lying to us. We might wonder whether our poker opponent is bluffing,

whether our partner is being honest when she tells us she loves us, or whether our boss is really planning to give us the promotion he has promised. This task is particularly important for

members of courtroom juries, who are asked determine the truth or falsehood of the testimony given by witnesses. And detecting deception is perhaps even more important for those whose job is

to provide public security. How good are professionals, such as airport security officers and police detectives at determining whether or not someone is telling the truth?

It turns out that the average person is only moderately good at detecting deception and that experts do not seem to be much better. In a recent meta-analysis, researchers looked at over 200

studies that had tested the ability of almost 25,000 people to detect deception (Bond & DePaulo, 2006). The researchers found that people were better than chance at doing so but were not

really that great. The participants in the studies were able to correctly identify lies and truths about 54% of the time (chance performance is 50%). This is not a big advantage, but it is

one that could have at least some practical consequences and that suggests that we can at least detect some deception. However, the meta-analysis also found that experts—including police

officers, detectives, judges, interrogators, criminals, customs officials, mental health professionals, polygraph examiners, job interviewers, federal agents, and auditors—were not

significantly better at detecting deception than were nonexperts.

Why is it so difficult for us to detect liars? One reason is that people do not expect to be lied to. Most people are good and honest folk, and we expect them to tell the truth, and we tend

to give them the benefit of the doubt (Buller, Stiff, & Burgoon, 1996; Gilbert, Krull, & Malone, 1990). In fact, people are more likely to expect deception when they view someone on a

videotape than when they are having an interpersonal interaction with the person. It’s as if we expect the people who are right around us to be truthful (Bond & DePaulo, 2006).

A second reason is that most people are pretty good liars. The cues that liars give off are quite faint, particularly when the lies that they are telling are not all that important. Bella

DePaulo and her colleagues (DePaulo et al., 2003) found that in most cases it was very difficult to tell if someone was lying, although it was easier when the liar was trying to cover up

something important (e.g., a sexual transgression) than when he or she was lying about something less important. De Paulo and colleagues did find, however, that there were some reliable cues

to deception.

Compared with truth tellers, liars:

- Made more negative statements overall

- Appeared more tense

- Provided fewer details in their stories

- Gave accounts that were more indirect and less personal

- Took longer to respond to questions and exhibited more silent pauses when they were not able to prepare their responses

- Gave responses that were briefer and spoken in a higher pitch

A third reason it is difficult for us to detect liars is that we tend to think we are better at catching lies than we actually are. This overconfidence may prevent us from working as hard as

we should to try to uncover the truth.

Finally, most of us do not really have a very good idea of how to detect deception; we tend to pay attention to the wrong things. Many people think that a person who is lying will avert his

or her gaze or will not smile or that perhaps he or she will smile too much. But it turns out that faces are not that revealing. The problem is that liars can more easily control their facial

expressions than they can control other parts of their bodies. In fact, Ekman and Friesen (1974) found that people were better able to detect other people’s true emotions when they could see

their bodies but not their faces than when they could see their faces but not their bodies. Although we may think that deceivers do not smile when they are lying, it is actually common for

them to mask their statements with false smiles—smiles that look very similar to the more natural smile that we make when we are really happy (Ekman & Davidson, 1993; Frank & Ekman,

1993).

Recently, advances in technology have begun to provide new ways to assess deception. Some software analyzes the language of truth tellers, other software analyzes facial microexpressions that

are linked with lying (Newman, Pennebaker, Berry, & Richards, 2003), and still other software uses neuroimaging techniques to try to catch liars (Langleben et al., 2005). Whether these

techniques will be successful, however, remains to be seen.

- 4102 reads